I want to go into more detail on Laurentian, digging into finances, and correcting one or two things I got wrong yesterday. An unfortunate amount of time is going to be spent dragging Laurentian for bad data practices, but that can’t be helped.

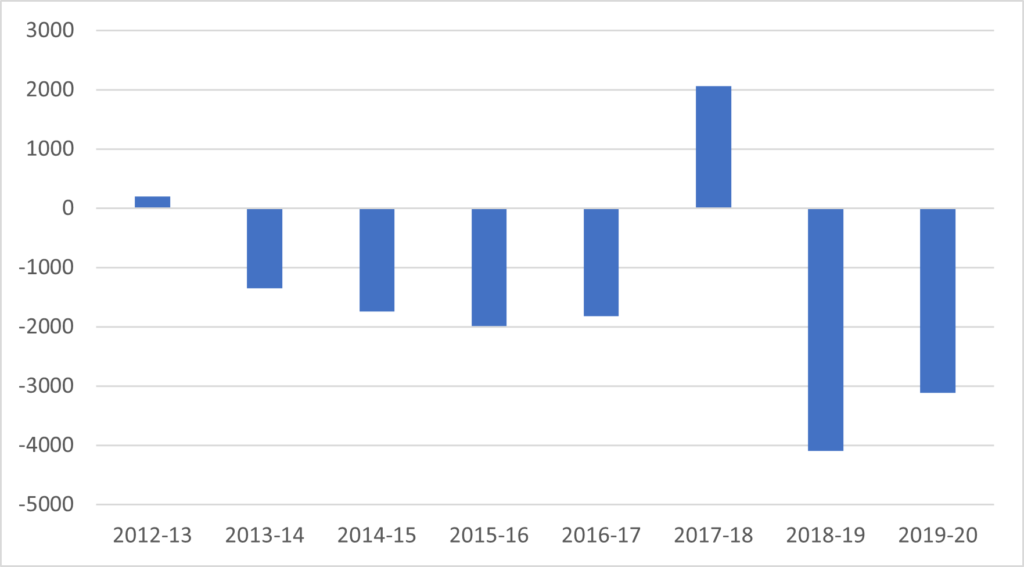

Let’s go back to this graph I showed yesterday. With a little bit more digging, I see that Laurentian claims that there were about $8 million in outstanding deficits prior to 2012-13, and that they are claiming an anticipated deficit of $5.6 million for 2020-21, with the losses mainly due to COVID. I have no reason to doubt any of those figures. What that tells you is they have about $25 million in losses from operations over the last 15 years or so. This still leaves about $11 million to account for, given there are apparently $36 million in allegedly reserved funds that have disappeared, but we’ll leave that for someone else to figure out.

Figure 1. Laurentian Net Revenue, 2012-13 to 2019-20 (in thousands)

The question we need to ask ourselves here is: why was Laurentian continually running such high deficits? There are basically three reasons posited in Laurentian’s affidavits: not enough students, staff are too expensive, and classes and programs are too small to be economical. Let’s look at each of these.

On the subject of student numbers, I just flat out do not buy what Laurentian is selling. Between 2012-13 and 2018-19, according to data Laurentian filed with the provincial government (see here), enrolments rose slightly (a little less than 1%). That was below the provincial average, but significantly better than its fellow northern institutions fellow northern institutions Algoma (-13.9%), and Nipissing (-5.4%). Laurentian tries to diminish this success in the affidavits by pointing to the drop in local students (20%), and claiming that the increase in numbers, which are mainly in online and graduate programs, are “unsustainable”. This a pure assertion on Laurentian’s part – literally no evidence is provided to back up the claim of unsustainability.

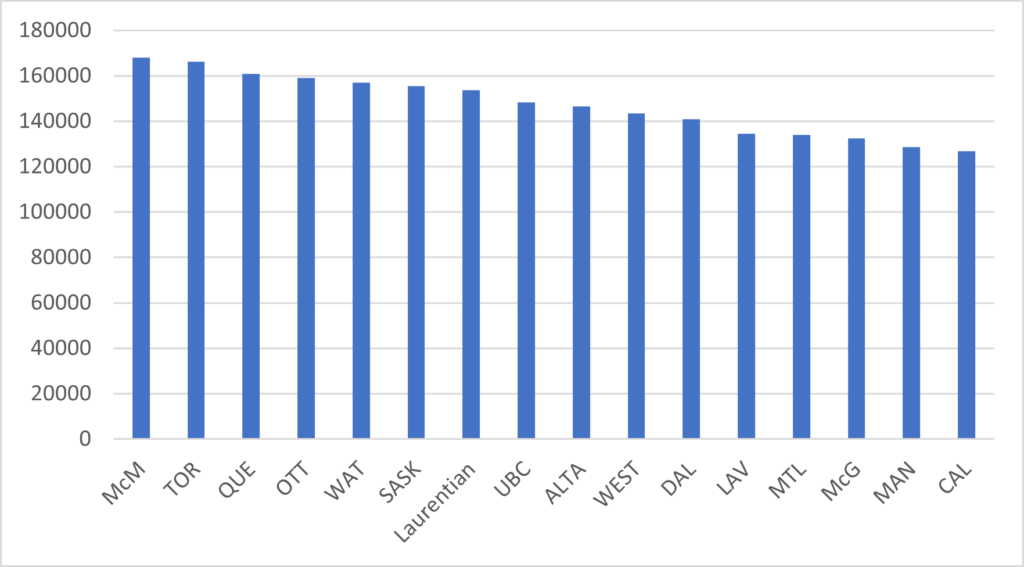

Another line of argument – not one that Laurentian makes directly, but it’s implicit, is that Laurentian professors are pretty expensive. And, look, obviously, “expensive” is in the eye of the beholder, but as Figure 2 shows, little Laurentian, not by any means a research powerhouse (SNOLAB and that CFREF in Mineral Exploration notwithstanding) does pay some pretty wild salaries. In fact, as Figure 2 shows, median salaries at Laurentian are slightly above the mid-point of the U-15 (and, amazingly, $20,000 per year higher than at McGill).

Figure 2: Median Salaries, Laurentian plus the U-15, 2018-2019

Now, I’m sure lots of people will want to claim all sorts of innocuous reasons for this: maybe the profs are older, it’s about the age pyramid, etc. To which the answer is: yes, but from the perspective of being able to make payroll, it’s all totally irrelevant. Governments don’t give institutions higher funding because their professors are older, and you can’t charge higher tuition on that basis either. No matter how you explain the high number, it’s a problem.

On its own, this isn’t necessarily a huge problem. Even if you lopped average salaries down to McGill’s level, you’d only be saving about $7 million a year – not nothing, and certainly not enough to get the university back on track. But where it would get much worse is if the institution had too many profs. And this is the point the university has been making for quite some time: that it has way too many small-enrolment course and programs (partly a function of offering programs both in English and French, which raises per-student costs significantly). Here’s a couple of interesting passages from the court filings:

“Laurentian offers 132 undergraduate programs and 43 graduate programs. Approximately 25% of students are enrolled in the top five programs, approximately 62% are enrolled in the top 25 programs and 83% are enrolled in the top 50 programs.”

And:

“Of the 1,902 courses offered by LU in the Winter 2021 semester: (a) 162 courses (8%) have five students or fewer enrolled; (b) 180 courses (9%) have between six to ten students enrolled; (c) 1,018 courses (53%) have between eleven to fourteen students enrolled; and (d) 568 courses (30%) have fifteen or more students enrolled.”

OK, now the general story these pieces tell isn’t wholly wrong – Laurentian does have somewhat higher staff:student ratios than Lakehead, Winnipeg and VIU, which are probably its closest comparators. But I think you’ll find that most institutions have similar dispersions across programs. And as for those class size numbers, I call bullshit. The university’s own “class size” data produced for the Common University Data Ontario (CUDO) Set suggests the institution has fewer than 950 undergraduate classes. So, for that figure about class sizes to be right, the university is either offering as many graduate courses as undergraduate ones (which would be utterly bananas given undergrads outnumber grads by a factor of over ten to one at Laurentian) or they are using a different definition of “courses” here than they do in their CUDO data.

(Do you see how hard it is to evaluate institutional claims when everyone insists on playing with inconsistent data all the time? They’ll never learn. So annoying)

What you have here is – I think – evidence of light overstaffing, mainly to deal with its mission to teach in both official languages. Now, Laurentian does get an extra stipend for that from the government – perhaps not enough to cover these costs, but still they aren’t entirely free from offset. The bigger deal is the cost per staff member. Fix that – and to be fair it’s the kind of thing that seems solvable reasonably quickly with some buy-outs – and you’ve mostly fixed the cost-side problem.

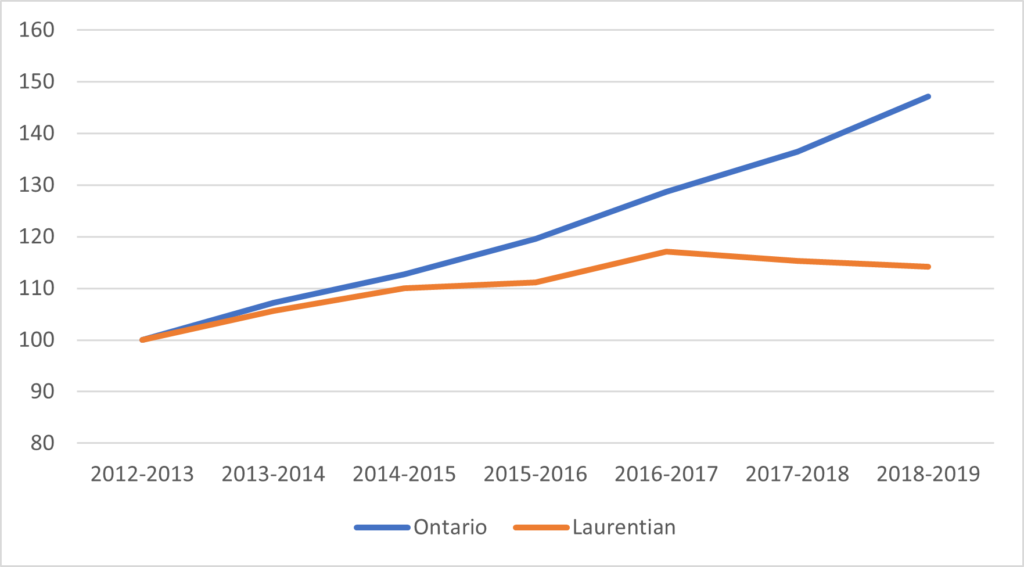

But the bigger issue, I think, is on the revenue side. If you just look at raw revenue growth between 2012-2013, Laurentian looks pretty much like the rest of Ontario – growth of a little over 15%, after inflation. But the big difference was that at Laurentian roughly half of that increase came from research funding, which can’t (or shouldn’t) be used to help pay the day-to-day bills. The important thing is that Laurentian was being left behind when it came to tuition funding – a reflection of the fact that it was not playing the international student game the way everyone else was. As Figure 3 shows, tuition fee income – that is the stuff that really matters in terms of keeping the lights on – only rose by 14% after inflation at Laurentian between 2012-2013 and 2018-2019, whereas it rose by 47% across Ontario universities as a whole.

Figure 3: Tuition as an Indexed Percentage of Total Revenue, Ontario v. Laurentian, 2012-13 to 2018-19

You know where this is going: it’s all down to international students.

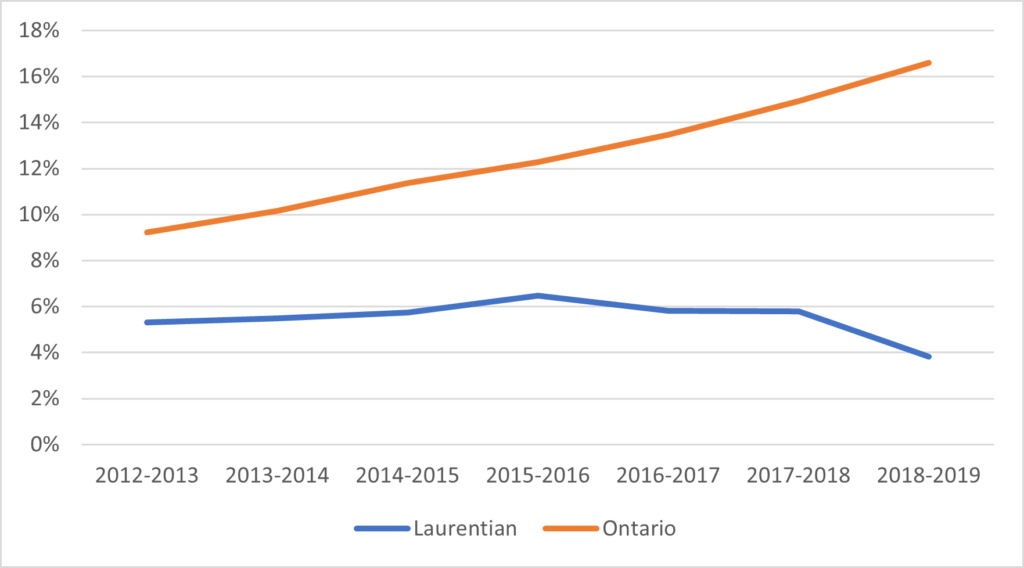

Figure 4: International Students as a Percentage of Total Student Population, Ontario v. Laurentian, 2012-13 to 2018-19

Put it this way: if Laurentian university had increased its international enrolments at the same rate as other Ontario universities, it would have an extra 277 students, and another $7.8 million in gross revenue in 2018-19, as well as another $20 million or so in the bank from previous years (anyone who says this can’t be done in Sudbury needs to take a trip to Sydney, Nova Scotia). If its average salary costs had been like McGill’s over the past seven years, present annual costs would be reduced by $7.5 million, and the institution would be around $35 million better off in total costs.

This isn’t rocket science. As Mr. Micawber said, “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery.” Laurentian, caught up in its considerable research success, just seems to have stopped paying attention to the nuts and bolts of keep the operating budget in balance. The results are dispiriting. But on the other hand, the road back to health is pretty clear, too.

12 Responses

All good points. Konrad Yakabuski, writing in the Globe today, notes that a number of the foreign students Laurentian did attract were Saudi, and were pulled. Moreover, they did try to attract international students, and failed: “At Laurentian, the withdrawal of more than 150 Saudi students after a 2017 chill in relations between Ottawa and Riyadh resulted in a one-quarter drop in foreign enrolments almost overnight. After that, the university set a goal of attracting 1,000 foreign students within five years, but it struggled to meet the target – even before the pandemic hit.” The problem is with needing to stake one’s survival on foreign enrollments, in the first place.

Secondly, I wonder if Laurentian’s salaries are inflated because the university tried to manipulate faculty with merit increases, given to whoever was doing anything expensive enough. They certainly landed a lot of grants. This might show a wider failure, in a culture that rewards expense — hence grantsmanship — rather than seeing it as a necessary evil.

There are a couple of elephants in the room here. One is that Ontario drastically underfunds post-secondary education. Laurentian University is particularly vulnerable to this underfunding because of all the programming it has to offer as a bilingual, regional university. Using research money to fund day-to-day operations is a clear sign of desperation in the face of the underfunding–as is all of our universities’ reliance on tuition, foreign or not.

The second elephant: post-secondary education in Ontario should be freely available to all of Ontario’s qualified students. As things stand, students exit colleges and universities drowning in debt., unless they’re members of the wealthy elite, of course.

As someone who has used OSAP in the past, and is currently using it to further my education at an institution in another province, I have to say that the “student debt problem” is largely not a problem for Canadian students outside of the GTA. Tuition rates are relatively reasonable, and the average undergraduate debt load in Canada is about $17k. Add on that no government student loan program in Canada charges more than prime + 2% (currently 4.45%), and the existence of the RAP, student loan debt in Canada is largely VERY manageable for anyone who bothers to use the resources available to them.

To what extent has Laurentian’s financial crisis arisen from the refusal of well paid, elderly professors to retire and make way for less well paid younger faculty?

To what extent is Laurentian’s bureaucracy top heavy?

Have you contacted LUFA, the teacher’s union, for their input?

they would tell you that Laurentian funds departments based on number of majors and not total students enrolled in all of a department’s classes.

for example, a medical anthropology course may have 2 anthropology majors in it, but it may have 30 Biology majors.

for that class, in essence, that class is only being paid for by the 2 anthro students, which won’t cover the cost for that class.

While the biology department gets the funding for the department for those 30 students. which would mean that the Biology department is possibly over staffed

another thing you can look into is how Laurentian funds it’s federated Universities: University of Sudbury, Thornloe University, and Huntington University.

University of Sudbury professors’ union just completed bargaining for a new contract. there is talk in the university community that the University of Sudbury is in quite the financial trouble too.

It was a year or two ago that Laurentian changed how it funded the Federated Universities. My understanding it used to be funded per student. But now it’s per major through those schools.

For example the Communications department is run out of Thornloe University. I took a Communications course at LU many years ago. I was in Commerce though. then, I think, TU received funding based on me being in that course. but now the school would not get that money.

something concerning though about this, the previous president, Dominic Giroux, is now the president of Health Sciences North, our hospital up here in Sudbury

A couple of things: – In terms of faculty members’ salaries, Laurentian University can only be compared to other universities in Ontario for obvious reasons, viz., each Canadian province has its own monetary and fiscal policy and, accordingly, in this context, levels of income. Otherwise, comparison with universities in other provinces would be unfair (unless a unified scale is used to interpret the salary levels between the provinces). Laurentian University faculty members are among (the union, LUFA, should have tangible data on this) the least paid in Ontario. The faculty salary level has managed to somehow catch up over two or three past contracts (do not remember exactly when, but likely between 2008 and 2016).

– For most of the last decade (2010-2020) the former university president decided that the university stop paying graduate teaching assistantships to international graduate students, and, hence and in big part, the downfall in the headcount of this category of students.

Caution needs to be applied to the concern that LU offers “too many programs with low enrolments”, and the resulting implication that programs with low enrolment should be canceled in favour of programs “the majority of students want to take”. In many instances, course enrolments (and thus allocation of teaching ressources) can be best optimized by servicing a broad spectrum of small programs, as opposed to locking in course offerings within the confines of a more limited and monolithic programming model based on popularity. This can be achieved by designing programs which, in spite of being small, can utilize and share courses and other teaching ressources that are already in place, while requiring little to no new courses. For instance, small to moderate-sized programs such as chemistry, biochemistry, forensic science and environmental science share numerous common courses at all levels (e.g., analytical chemistry, instrumental analysis, inorganic chemistry, physical chemistry) which, in absence of such program diversity, would not have sufficient enrolment to justify allocating teaching ressources toward their offering.

So long as they are designed with parsimonious allocation of teaching ressources in mind, diversity and breadth of program options is an asset to a university, not a liability. The optimization of teaching ressource allocation should be the focus here, not reduction of program offerings.

Two points: first, having a lot of programs with cross-requirements is good, but it requires goodwill about which program receives credit (and funding) for student enrollments, and that nobody tries to hoard them. A situation of scarcity isn’t likely to strengthen interdisciplinarity. Moreover, I’ve seen more than one interdisciplinary program destroyed because one of the contributing departments decides to replace (say) the two sociologists who are cross-listed to Polynesian Studies with two experts in internet culture.

Second, a wide range of programs is good, even if some have lower enrollment, because we don’t know what will have higher enrollment in the future. It’s irresponsible to bet on only the programs popular at the moment remaining popular ten or twenty years from now.

Hi Alex,

I heard your great interview on the radio the other day.

What I do not get in all this is why no one talks about the role of the former president in all this. He is almost for certain to be blamed for a lot of this as he only left a year ago. With being only 34, he was the youngest university president in Canada ever when he took over LU. (https://www.thestar.com/news/insight/2010/05/08/dominic_giroux_canadas_youngest_university_president.html).

This is like having a toddler driving your truck! I dont understand why there is not more focus on this. And the ridiculous thing of all this is that he is now the CEO of the hospital. Are we going to see the same for the northern Ontario hospital now?

You cannot deny that his timing was fantastic as he left the LU ship just prior to sinking.

Cheers,

Rasmus (researcher at LU)

Bam!. Too true.

You bring up the University of Cape Breton as the model Laurentian should have followed, but as of September 2020 they were running a $6 million deficit (https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/cape-breton-university-deals-with-16-million-revenue-loss-due-to-covid-19-1.5731112). Their overreliance on international students meant they were impacted more than other universities their size from COVID-19 travel restrictions.

As the Globe and Mail recently pointed out, Laurentian faced a similar setback when Saudia Arabia pulled 150 students in 2017. The fact Canadian universities must rely on recruiting international students to remain in the black does not seem like the most prudent fiscal model. When geo-political events out of your control (whether it’s a pandemic or an autocratic government) can have such a huge impact on your financial stability, maybe it’s time to consider sufficient public funding to support these institutions.

Cannot have canadian universities relying on foreign students to keep them afloat.

I was under the impression that canadian universities were here to service our kids first. ???