After three blog posts looking at historical data on financing (see here, here and here), I thought I should do one final one which tries to tease out some lessons.

Let’s focus on what I think are the key graphs from yesterday:

Figure 1: Total Institutional Income per FTE Student by Source, Canadian Universities, 1962-63 to 2020-21, in constant $2022

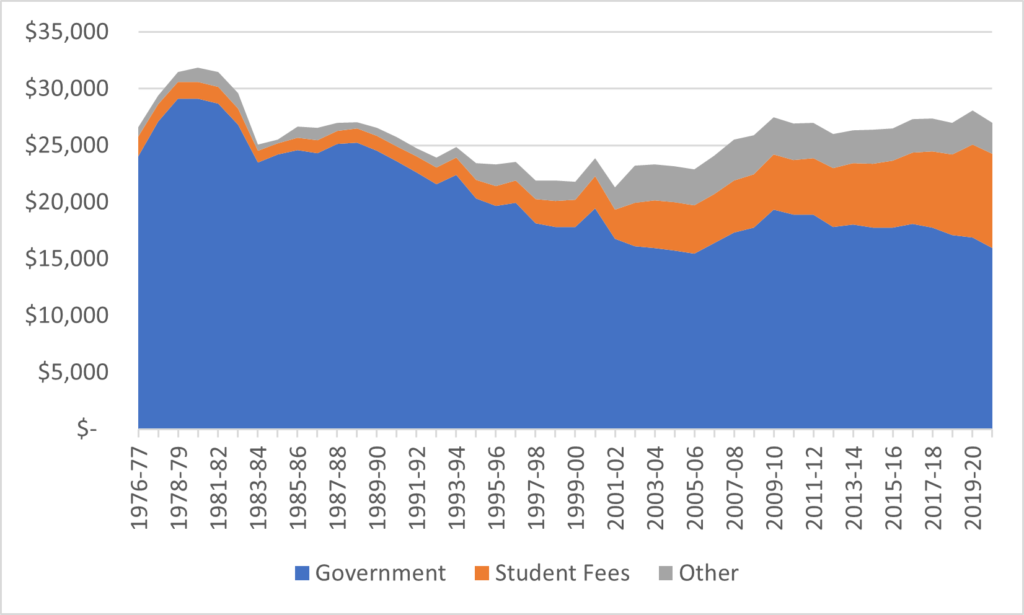

Figure 2: Total Institutional Income per Full-Time Student by Source, Canadian Colleges, 1976-77 to 2020-21, in constant $2022

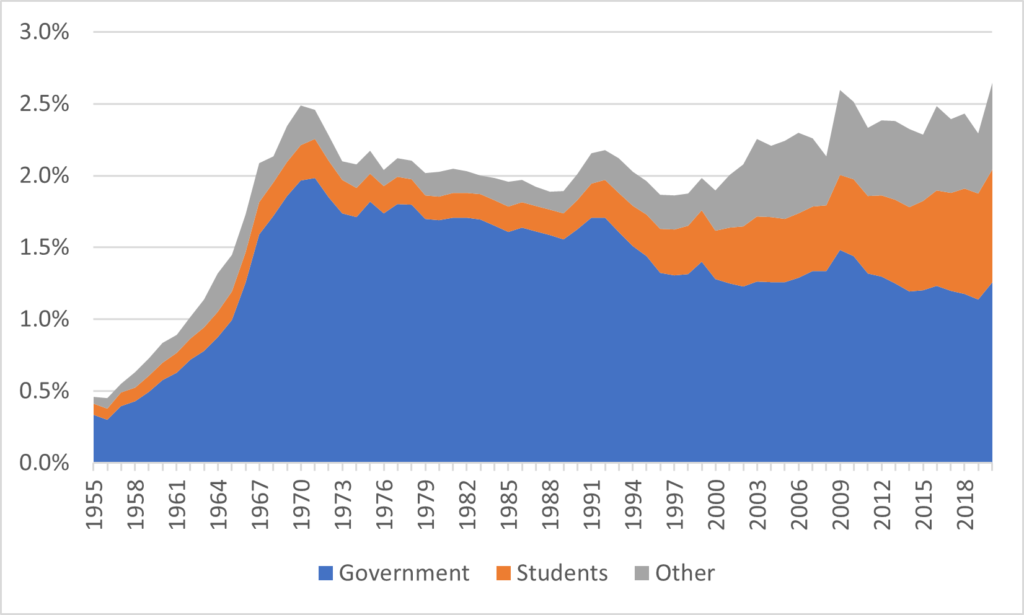

Figure 3: Total Institutional Income as a Percentage of GDP, by Source, Canadian Universities, 1955-56 to 2020-21, in constant $2022

These are all showing roughly the same two things. First, the peak years for public funding of higher education, no matter how you measure it, were in the 1970s. Since then, with the exception of a brief recovery in the early 2000s, it’s pretty much been all downhill. This is not a partisan thing. Governments of various stripes and various levels have all been complicit in this erosion of public funding. For those of you of a certain age who still blame everything on the Martin Budget of 1995 – that event doesn’t even rate a blip on these charts, invisible against the larger background of provincial cutbacks (at least in relative terms) which began in the late 1970s.

Second, at the same time, the peak years for total funding are, arguably, right now. From the late 1970s until the mid-1990s, when public funding fell, so too did total institutional income when measured in per-student or per-GDP terms. And that was because institutions either did not have the tools or the will to improve their situation through raising funds privately through tuition fees and self-generated revenue. That changed in the mid-90s, and since then institutions have aggressively pursued private funding, so much so that not only have they made up for another couple of decades of relative decline but restored total income to its previous heights.

These points suggest the need for more reflection when using the term “austerity” (the system has as much money as ever) and how this government or that ruined higher education. The transition from a higher education system that is overwhelmingly publicly-funded to one which is majority-private funded was over 40 years in the making, and did not, in the end, result in fewer resources per student.

Now, that said, the transition from being public-funded to publicly-aided has not been costless or friction-free. The difference between back then and now is that universities and colleges must work for their money. It’s not just given to them on a plate the way it was 50 years ago; they have to compete, and they have to sell. That doesn’t just happen by itself: it requires a different set of employees. And so, despite having similar total amounts of income, less of this income is available to fund “the academic project.”

It is not clear exactly what a way out of this situation would look like. You can’t really wave a magic wand and replace all that private funding with public money and turn the clock back to 1974. Again, this process of shifting from a publicly-funded to a publicly-aided system has been a 40-year long, deeply pan-partisan process. That’s what you call a big ol’ consensus. To the extent that any government wants to increase funding these days, it’s nearly always tied either to system expansion (whether targeted or not). In the last ten provincial election campaigns, I believe only the Nova Scotia Liberals have suggested raising core budgets, and even that was tied to a specific sector (colleges).

I get that people inside higher education don’t like “the hustle”. I understand that many are queasy about the way the pursuit of international students has been so brazenly commercial. But the likely alternative is not a restoration of public funding; it’s no money at all. And so, we return to the hard point: an increase in reliance on private funding is not absolutely necessary: but the alternative is a heavier belt-tightening than almost anyone in higher education will have yet experienced. Some of the cuts would be painless to the academic mission – if you don’t want to chase private sources of income then whole swathes of non-academic staff can be released – but surely not all of them. Pain would be real.

So as a result, it means that we muddle through, doing the best we can, maintaining as much of the mission as we can, with the cards that are dealt to us. It should mean a universal interest in squeezing inefficiencies out of the system to make more money available for the academic mission. We do what we can and have been doing so for decades now.

Onwards!

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thank you for doing this work, and especially for breaking it out by funding per FTE, that helps me understand the scale of the shift. However, although it is going there, I would say that as long as government funding remains above 50% of total revenue that universities remain publicly-funded, not publicly-aided. But it’s certainly a shift over time of what governments feel is important about post-secondary, shifting from a public to a private good in their understanding of it.

Likely more provinces will shift to targeted funding to fund programs they feel are public good programs and away from ones that are private good ones. This will be interesting to watch as we see what programs are considered public good (health and education? or business students to grow the economy? or trades students to support industry and construction?).