The week before last, the Canadian Centre for the Study of Living Standards (CSLS) put out a report (available here) on trends on low-paid employment in Canada from 1997 to 2014 (meaning full-time jobs occupied by 20-64 year olds where the hourly earnings are less than 66% of the national median). It’s an interesting and not particularly sensationalist report based on Labour Force Survey public-use microdata; however one little factoid has sent many people into a tizzy. Apparently, the percentage of people with Master’s or PhDs who are in low-wage jobs (where the hourly earnings are less than two-thirds of the national median) had jumped from 7.7% to 12.4%. This has led to a lot of commentary about over-education, yadda yadda, from the Globe and Mail, the CBC, and so on.

This freak-out is a bit overdone. I won’t argue that the study is good news, but I think there are some things going on underneath the numbers which aren’t given enough of an airing in the media.

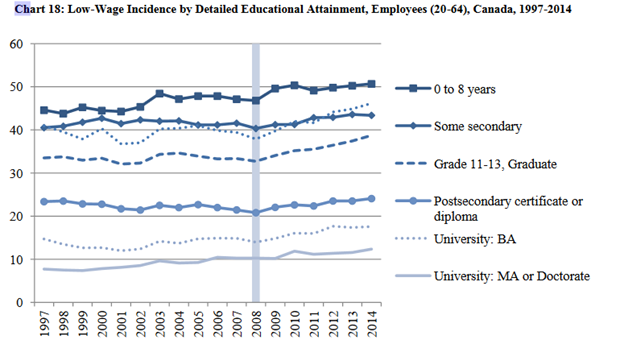

First of all, as CSLS explains in great detail, the two important findings are that the incidence of low-wage work in the economy has stayed more or less stable, and second, Canadians on the whole are a lot more educated than they used to be. This leads to a compositional paradox: even though all seven levels of education saw increases in the incidence of low-wages (see Figure below), overall the fraction of Canadians with low wage jobs dropped ever-so-slightly from 27.9% in 1997 to 27.6% in 2014.

Now you have to be careful about interpretation here, particularly with respect to charges of “over-education”. Yes, the proportion of grads in low-wage jobs is going up. But the average wage income of university graduates is actually increasing: between 1995 and 2010, it rose by 6% after inflation. And that’s while the number of people in the labour force with a university degree increased by 94%, and the proportion of the labour force with a university degree jumped from 19.3% to 28.7% (I would break out data on Masters/PhD specifically if I could, but public Statscan data does not separate Bachelors from higher degrees).

What that tells us is that the economy is creating a lot more high-paying jobs which are being filled by an ever-expanding number of graduates. But at the same time, more graduates are in low-wage jobs, which suggests that while averages are increasing, so is variance around the mean.

Another factor at work here is immigration. Since the mid-1990s, the number of immigrants over 25 with university degrees has increased from 815,000 (23.2% of all degree holders) to 1.87 million (33% of all degree holders). It’s not clear how many of those have graduate degrees (thanks Statscan!) but I think it’s reasonable to assume, given the way our immigration points system works, that the proportion of immigrants with advanced degrees is even higher.

The problem is that immigrants with degrees – particularly more recent immigrants – have a really hard time in the Canadian labour market, particularly at the start (see a great Statscan paper on this here). To some extent this is rational because the degrees and the skills they confer are genuinely not compatible (see my earlier post on this), and to some extent it reflects various forms of discrimination, but that’s not the point here. There are over one million new immigrants with degrees over the past fifteen or so years, many of them from overseas institutions. The CSLS-inspired freak-out is about the fact that over the past 17 years the number of degree-holders has increased by 450,000 (of which 130,000 are at the Master’s/PhD level). Simple logic suggests that most of the problem people are seeing in the CSLS data is more about our inability to integrate educated immigrants than it is about declining returns to education among domestic students. I know the data CSLS uses doesn’t allow them to look at the results by where a degree was earned, but I’d bet serious money this is the crux of the problem.

So, you know, chill everybody. Canadian graduates still do OK in the end. And remember that comparisons of educational outcomes over time that don’t control for immigration need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Employers consider many factors when hiring, and education is often only a small part of it. Personality, presentation, confidence, and genuine interest in the job weigh fairly heavily in the interview process. Some students might be better served by building their communication, social, and interpersonal skills than going for another degree in the hope that education will trump a good interview.

“So, you know, chill everybody. Canadian graduates still do OK in the end.”

So, your message is we’re only discriminating against immigrants, so no need to worry? Wow.

P