There was an interesting Statscan paper out yesterday that made some fascinating observations about education, immigration, and human capital. With the totally hip title, The Human Capital Model of Selection and the Economic Outcomes of Immigrants (authors: Picot, Hou and Qiu), it’s a good example both of what Statscan-type analyses do well, and do poorly.

At one level, it’s a very good study. It uses the Longitudinal Administrative Databank (Statscan’s coolest database – it’s a longitudinal 20% sample of all of the country’s taxfilers) to follow the fates of newcomers to Canada in terms of earnings. What they find is that in the first few years after entry, the very large wage premiums that “economic class” immigrants (as opposed to “family class”) with degrees used to have over immigrants without degrees has shrunk substantially. However, over the longer term, the study also finds that educated immigrants have a much steeper earnings slope than those with less education – which is to say that if you shift the lens from “what are immigrants’ labour market experiences in their first three years in Canada”, to “what are immigrants’ labour market experiences in the first ten-to-fifteen years in Canada”, you get a much different, and more positive story.

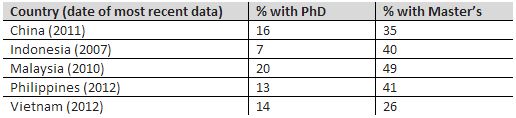

Now, a lot of people want to know why immigrants with degrees aren’t doing as well in the short term, even if the decline in long-term fortunes isn’t as severe as first thought. The authors don’t answer this question, but many others have come up with hypotheses. When you hear stories about immigrants doing worse than they used to in the labour market, even holding education constant, it’s easy to jump to conclusions. Canadian immigration since the 1980s has increasingly been from Asian countries, so it’s easy enough to conjure up some racism-related theories about the decline. But I want to point something else out. Below I reproduce a table from a this recent UNESCO report on higher education systems in Asia. It shows the distribution of university professors by various levels of qualifications.

Table 1: Highest Level of Higher Education Instructors’ Academic Attainment, Selected Asian Countries

Here’s the problem: Should we really assume that a Bachelor’s degree from Indonesia confers the same skills that one from the US or Europe does? Probably not. And yet every single Statscan study that looks at education, immigration, and earnings assumes that a degree is a degree, no matter where it’s earned. I understand why they would do that; how else would one judge equivalencies? And yet choosing to ignore it doesn’t help either. The reason today’s university-educated immigrants are doing worse than the ones of 30 years ago may simply be that they have lower average levels of skills because of where they went to school.

None of this is to suggest racism isn’t a factor in deteriorating incomes for new immigrants, or that Canadian employers aren’t ridiculous and discriminatory in their demands that new hires have “Canadian experience”. It’s simply to say that degrees aren’t all made the same, and it would be nice if some of our research on the subject acknowledged this.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

This post on degree equivalency got me thinking about equivalency at the doctoral level. In the humanities at least, the doctoral journey in North America has been stretched out into a long-sometime almost decade long– marathon of comps, fields, and (eventually) doing original research in the form of a doctoral thesis or (at some institutions) a series of linked articles published in journals. But in the UK and Australasia, the thesis is the key, allowing well organized students who can work on it full-time to complete in about 4 years (many do so in 3 years if they don’t do much teaching enroute). After half a dozen years in an academic job, I very much doubt if there is any difference in performance, or even if the route to the degree matters anymore. Has any research been done on whether the form of the doctoral degree has any impact on the outcome? If it doesn’t, why not revert to the British model and cut those completion times in half?

That’s an excellent question. My (cynical) guess is that if we didn’t keep lengthening the PhD then any old riff-raff could get in….

If I can offer a (slightly) less cynical explanation, I think that it has to do with the ever-greater, more-difficult competition for tenure-track jobs. This tends to raise the stakes for the dissertation, from a sign of competence to some sort of attention-grabbing magnum opus.

Besides, doctoral candidates need lots of time to pad their resumés before hitting the job market. I have colleagues with British degrees, who often had a hard time getting jobs, though they held degrees from very good institutions. They couldn’t boast years of teaching experience, for one thing.