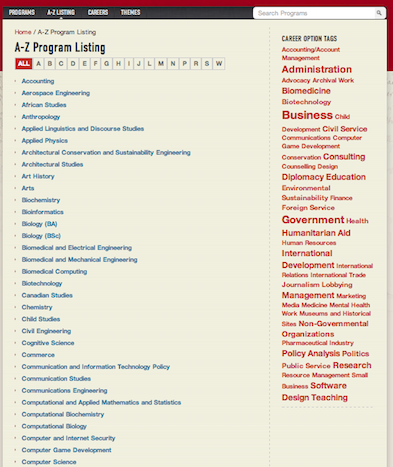

- Just some of the programs offered at Carleton

For a country as large a Canada it’s amazing what a fetish we make of smallness – with students packed into large institutions, there are economies of scale in terms of teaching and student services (admittedly, these economies are then splurged on research, but that’s a separate issue). But when it comes to attracting students, we try to hide bigness. Schools like to talk about how they “feel like” a small school, or give attention to students “as if it were” a small school.

This is a dumb idea for two reasons. First, it’s nonsense. Big schools can’t give a small school feel – they simply aren’t built to do so and it actually harms a university’s credibility and brand to pretend to be something they are not. That’s not to say big schools can’t give students a bit more of a human touch – the opposite of small administration needn’t be Borg-like administration – but raising expectations too high never does anyone any good.

Second, the attempt to play up smallness actually covers up big schools’ one enormous strength, and that is choice. Students love choice; if you look (as we do) at a lot of student surveys what becomes clear is that the most substantial critique students have of small schools is that they are, well, too small. As in, “limited.” Which isn’t something you can say about multiversities with a dozen or more faculties and 20,000 or more students.

Big means choice. Big means more options. Big means more opportunities. Big means not living for four years in a small community where everyone knows what you’re doing. One of the country’s comprehensive universities (my choices would be Ryerson, or Carleton, or perhaps Laval) needs to stand up in a strong marketing campaign and say “Proud to Be Big.” Not only would they stand out from the crowd, they’d be doing all other large-ish universities a service as well.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

While there is something attractive about the strategy that Alex suggests, here are two possible issues with this strategy:

1) Just touting the benefit of being large ignores the downsides of a large university. Thus, an even better recruitment strategy for a large university might be to offer student the best of both worlds: enjoying the social benefits of being in a relatively intimate setting in a modestly sized college or institute, while still having access to the broad opportunities that a multiversity provides. This is the rationale for the college systems that some large universities have, though maintaining robust colleges has often proved difficult in the face of the centralizing forces that exist in most large universities.

2) Emphasizing the choices available at mid-sized comprehensive universities might increase their vulnerability to competition from the largest universities. If intra-institution choice is the deciding factor in a student’s selection of a university, why not choose the largest ones that offer the most choices?

I, too, agree that there is something attractive in the strategy. Mid-sized Canadian universities are in an eternal search for identity, having neither the bucolic and avuncular charm of the small institutions nor the monumental grandeur of the 30,000+ institutions.

But wait, did not the same author just recommend that we should sort out the teaching duties on the basis of a quota of 160 students per year? And was not one of the benefits from such a move to be the elimination of small niche courses? And was not another the elimination of additional faculty positions? I have some sympathy with the third goal, the diminution of sessional lecturers, but would not the sum of these benefits lessen the ability of a mid-sized university to offer the diversity that the author proposes to be the basis of their charm in this piece?

Michael: With a self-imposed 400-word maximum I tend to pass up the opportunity for subtler distinctions, so those are fair points I would basically agree with. You might be right about the competition from bigger schools angle, though I would tend to think that your U of Ts or UBCs wouldn’t want to compete on choice – they’d want to compete on quality/reputation. It’s those large comprehensives which I think have the most trouble making a mark (so to speak) and who are in closer head-o-head competition with smaller schools who I think would benefit most from the strategy.

Rciahrd: fair question in your second para. My gut feeling is that it is choice at the level of program rather than the individual course which matters to prospective students, and the piece I wrote yesterday was more about reducing course offerings than programs per se (though it would at least curtail the rate of growth of new programs).

I meant “Richard”,of course. need a spell check on this thing…