I’ve had a couple of people say to me recently that in light of the current carnage, I must be having trouble getting business. “No time for strategy right now, huh?”

Wrong.

You see, “strategic planning” isn’t one single thing: it encompasses a huge variety of activities. And some of them, no, you probably don’t want to mess around with during an emergency. But others, you really, really do, and failure to do so is likely to make the carnage last a lot longer than it needs to.

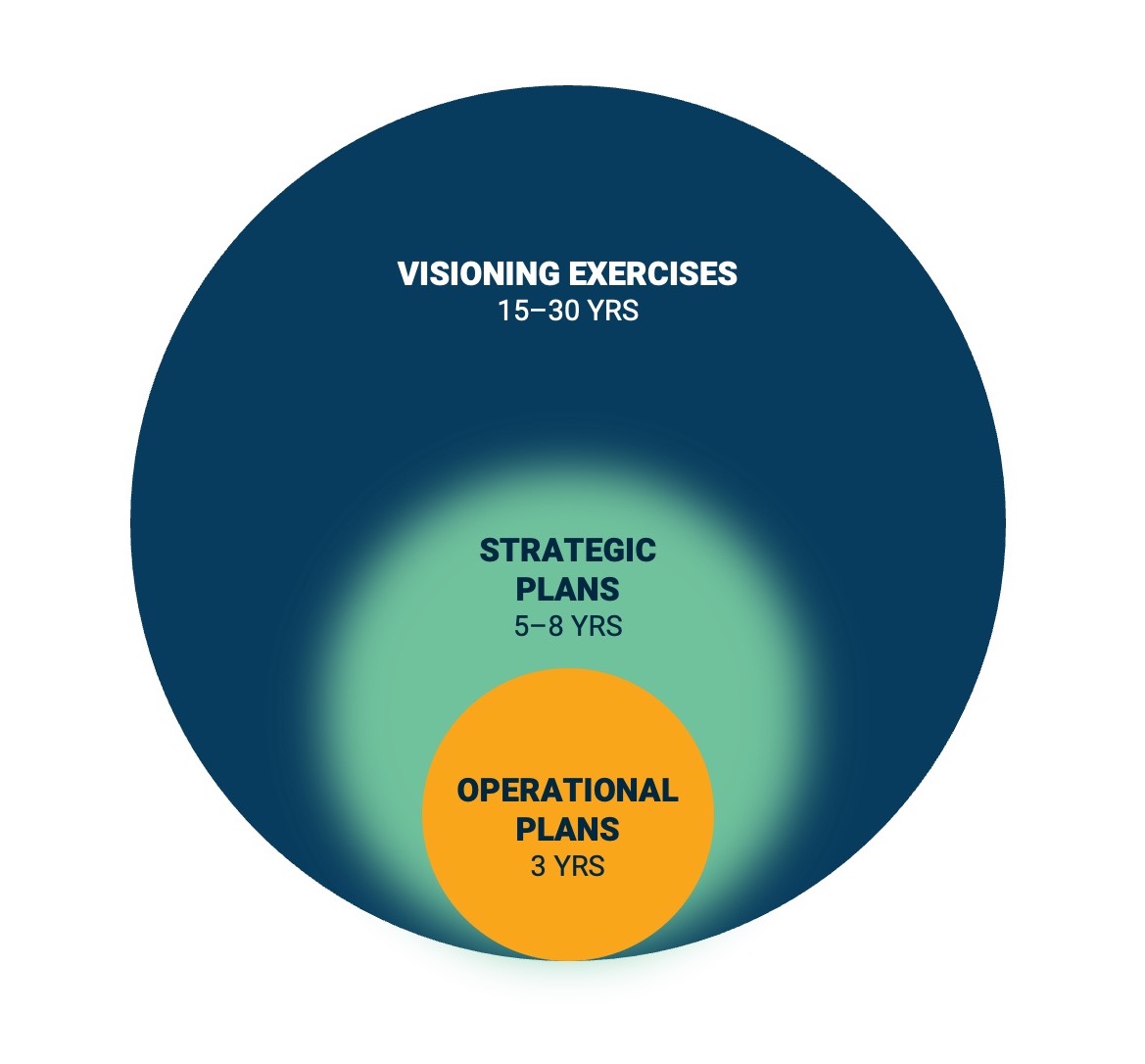

At the risk of vastly oversimplifying things, let me show you what I think of as the three “scopes” of strategic planning.

At one end of the spectrum, there is what I call “operational planning”—plans that tell everyone what they need to be doing for the next two or three years. There’s not a lot of strategy in these: they only make sense if they remain anchored to longer-term goals which have been worked out in a longer-term document. Then, at the far end of the spectrum, there are what I call “visioning” exercises, which aim to describe what the university wants to be 15 or 20 years hence (it can be longer: the University of Waterloo recently put together a vision extending to 2057). These exercises are low on strategy and even lower on planning: really, they just answer the question “where do we want go?”

In between, there are what we know more conventionally as “strategic plans” with all the vision/mission, goals/objectives that you’re probably familiar with. I have written about why I think relying solely on five-year plans for strategy is generally sub-optimal in some detail back here (tl;dr: five years is too short for a strategy to bear fruit and too long for operational planning to be useful), but the five-year standard remains, for the same reason the QWERTY keyboard does—path dependency is fundamental.

Now, of these three types of planning, can you guess which one institutions should forego in an emergency? Yup, it’s the five-year kind. Because it takes a long time to conduct and spends way too much time thinking about things 3-5 years out—too far out to be useful. But the other two types of strategic planning become more important.

It should be clear why short-term operational planning is absolutely necessary in an emergency. Someone needs to co-ordinate and prioritize various efforts, and everyone needs clear marching orders. Cool minds, clear heads, etc.

But in an emergency, you also absolutely need a one of those long-term visions so you know what to protect. I would argue that the real danger for most institutions is that without a really good long-term vision that emphasizes what is most important at the institution (and by implication what is not), their reaction to short-term crises risk being haphazard and deleterious to long-term goals. For an organization to reach its long-term destination, it must know what to protect in times of crisis. The worst thing you can do in a cost-cutting exercise is to get rid of the things that you will need when the crisis is over.

Now, obviously, an emergency is not the ideal time to start one of these long-term visioning exercises. But as the saying goes: the best time to have done one of these is five years ago, the second-best time is now. For those institutions who are in a real four-alarm emergency (Ontario colleges, say) it’s not crazy to run a truncated, quick process over the next few weeks to ask stakeholders what they want the college to look like in 2044. The key is to design a process which takes into account both internal and external stakeholders (too many of these exercises privilege the former over the latter). The results should be very instructive and can help inform key decisions about how to proceed over the next few weeks (hint: involve your Board members…a lot!).

But at other institutions (or faculties, or whatever the same logic applies at all unit levels), where the emergency is more slow-moving, and is for the moment only about two-alarm level (i.e. most universities, especially those outside Ontario), just go out and do a real consultation, right now. Figure out what kind of university you want to be twenty years from now, and then build your short-term plan to get you through the crisis.

The Vision is your map. Without one, you’re probably going to get lost. And there’s simply no need to get bogged down in process here. Better to have a simple, fast, jerry-rigged map than no map at all.

(If you’re having trouble coming up with how to design a fast process, let me know. I can set you up pdq.)