Good morning, all. This is the final blog for the year apart from tomorrow’s podcast. I am probably going to do one or two blogs if and when big news comes up during the summer (and we at HESA will have some big event-related news fairly shortly, so stay tuned). As usual, all feedback and suggestions for the blog are welcome—just drop me a note at president at higher ed strategy dot com. Regular daily service will return on Tuesday September 3rd.

But before I go, I wanted to finish up with one final thought about this year and what it means for higher education. It’s about Figure 1, which I discussed in this post from February, saying it showed the three eras of Canadian post-secondary finance

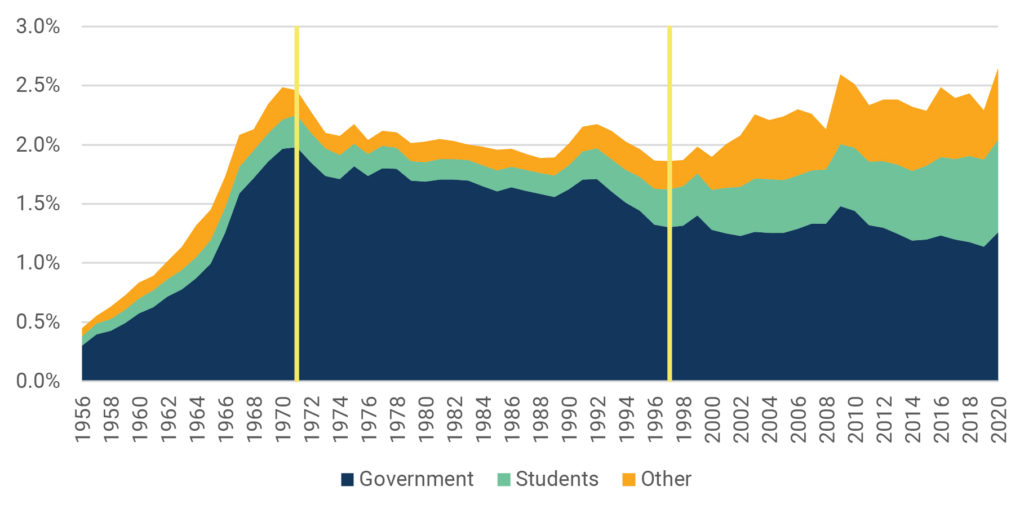

Figure 1: Total Income by Source, as a Percentage of Canadian Post-Secondary Institutions, 1955-56 to 2020-21

Briefly, my potted description was that the first era, up to 1971, was a golden era: post-secondary leaders could walk into Ministerial offices, demand money for any old project, and largely come away satisfied. Good times. Since then, the erosion of government funding as a percentage of GDP has been shrinking more or less constantly, from 2% to about 1% over the course of 50 years or so. That public funding crunch your institution has been feeling? It’s not a Ford thing or a Wynne thing or a Kenney thing…it’s not even a recent thing. It’s a 50-year pan-partisan thing. It is, one suspects, the expression of a very united will of the Canadian people. There is no reason to think such a trend is likely to reverse itself true, not even if (and God help me) we manage to “tell our story better.”

No one is coming to save us.

(Oh, you think the feds might riding to the rescue? Consider the fact that in real dollars, we are now significantly below the level of public funding for research that we were at when the Harper government was in power. Yes, really. And will remain so out to 2027-28 even under the exceedingly unlikely eventuality that all that money in this year’s budget actually materializes. No one is coming to save us.)

Since the erosion of public funding began, there have been two more eras of funding. In the first, lasting from 1971 to about 1997 or 1998, the fall in public funding was not offset by any increase in funding from private sources—the sector was not allowed to raise fees from tuition, and it had not really figured out how to generate a lot of private income After that, through to earlier this year, the sector reversed that trend and learned how to generate revenue through fees and other methods.

In fact, revenue generation became pretty central to the identity of Canadian post-secondary institutions this century. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that in the past 25 years, the sector never found a problem for which the solution was not on the revenue side. Until January 22nd. that is, when the feds pulled the plug on the international student game we’ve all been playing for the last decade or so.

Many people, including me, have speculated about what the financial hit from that decision will be. And that’s important, but it’s not actually the right way to look at things. In most of the country—Quebec and Alberta to some degree excepted—what has changed is that the whole notion of revenue-side solutions is pretty much over. For the next few years at least (maybe a decade) we are going back to that second age between 1971 and 1997 when total institutional revenues were falling as a % of GDP. Revenue-side solutions are over. We’re back in the age of cost-side solutions. And apart from anything else, that’s going to have huge implications for institutional cultures.

Like, we might have to centre efficiency for a change.

For the past couple of decades, we’ve just thrown bodies at problems as they arise. But now, we’re going to have to invest in technology and think through processes to optimize for lower labour costs. That doesn’t necessarily mean more institutional centralization, but institutions that want to permit units a degree of autonomy and administrative process differentiation are going to have to work a lot harder at making it work financially.

It for sure means we’re going to have fewer people on campuses. Everyone who complains about “administrative bloat” is about to find out how much they like it when institutions start shedding some pf these people.

It almost certainly means we’re going to offer fewer courses and programs. But those that remain will be more sustainable (again, I repeat the admiration I shared yesterday for the Berdahl/Malloy/Young book For The Common Good, which shows how this can be done without too much fuss at the level of graduate programming). But again, I am speaking in terms of outcomes. Think of the difference in culture. Think about how different institutions will be if their primary objective is to do fewer things better rather than more things indifferently. If operational excellence takes precedence over sprawl.

There will be losers in this process of course. But done right, the institutions that emerge on the other side might be better ones. Ones at which people really enjoy working. This process will undoubtedly involve pain, but the potential for gain is real, too.

The key to doing this while protecting the academic mission, of course, is that we will need to be a lot more deliberate about program and process design than we have been in recent years, and less prone to take “but we have always done it this way” as a rationale for doing anything. Institutions that will come out the other side in the best shape are ones that are clear in communicating the financial options, open-minded, values-driven, and inclusive in the search for solutions, and at the same time ruthless in seeking results

Achieving this requires having honest conversations, on campus, for sure. But it also requires a desire for us all to learn from one another. No single institution built the current model and no single institution is going to build the new one either. And wherever there is a chance for joint learning, our company will be there. If you’re interested in chatting about collaboration possibilities, let me know, I’d be happy to put people in touch with each other.

And so, friends: illegitimi non carborundum. Have a great summer. We’ll see you back here in twelve weeks.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post