The events of the last couple of weeks have kept everyone in the higher education sector in a whirlwind. But step back a minute. It’s worth thinking about the big picture.

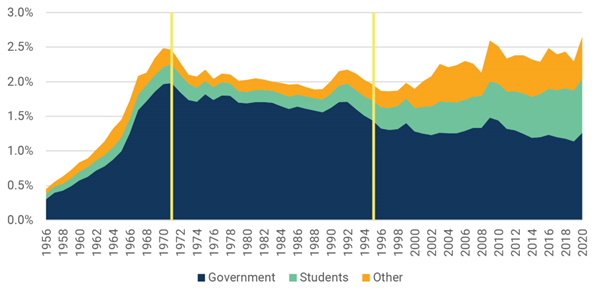

Some of you may remember this graph which I drew about a year ago, looking at the history of higher education funding in Canada. It shows total university and college income by source back to 1955-56. Looking at the trends across these six decades, I think it tells a story of three “eras” or “phases of financing.

Figure 1: Total Income by Source, as a Percentage of Canadian Post-Secondary Institutions, 1955-56 to 2020-21

The First Phase, which began a few years after the second world war, were what might be termed the “Glory Years.” An uninterrupted 12-fold run-up in expenditures which brought Canada to the point where public spending on post-secondary education rose to over 2% of GDP. And this was at a time when the proportion of young people attending university was around a third of what it is now. In that period up to 1971, there was not such thing as “funding formulas;” instead, university Presidents would just walk into Ministers offices and emerge with huge wodges of cash in their pockets. Truly glorious.

The Second Phase was between about 1971 and 1995. This was an era of unabashed decline. Government funding reversed course (as a fraction of the economy) and was not replaced by other forms of income. Part of this was that universities didn’t know how to increase income in other ways, and part of it was that they were simply not allowed to recoup revenue in the form of tuition fees (fee levels declined in real terms in the 70s and then stayed about even during the 1980s). Particularly towards the end of this period, from 1991 to 1994, government cuts made an enormous dent in the sector.

Suddenly, around 1995, things changed. Institutions were allowed to bring more money in from domestic tuition fees, and a lot more money from international students; Ontario deregulated international student fees in 1996, others soon followed suit. Institutions learned to self-generate more non-fee income. And for a few years—from 2000 to 2008—the erosion of government funding stopped and even briefly reversed from 2000 to 2010. When governments then returned to form and allowed funding to stagnate, institutions kept their incomes up by leaning even more heavily (exclusively is probably a better term) on international students.

And then two weeks ago, Marc Miller’s announcement came, which effectively reduced institutional fee income by a substantial—though as of yet still undetermined—amount (I’ll be working on that topic over the next couple of weeks). I think there is a pretty good chance that the Third Phase has has now ended, and we are heading into uncharted territory. I mean, it’s barely conceivable that we could keep the train going on fee income by raising fees to make up for lower numbers, but it’s not clear how many institutions can actually command the kinds of prices that would take (almost none in Ontario but elsewhere I think there may be opportunities). But the likelier path is that we’re heading into a Fourth Phase, a world of declining institutional revenues, just as we were between 1971 and 1995. It’s why everyone in the sector who actually understands what is going on is in shock and mourning, they can see budget cuts to match the loss of income barreling down the track, fast.

We can’t know the exact shape of the Fourth Path, but it’s worth remembering that the years of eroding income during the Second Phase wave were pretty awful. The mid-1990s, for those who don’t remember them, were bad. But there is a path through this. And that is, simply, to be ruthless about efficiency. Lower per-student funding and improved outcomes are not necessarily antithetical. Witness how Université de Montréal manages to produce world-class research outcomes with substantially lower levels of expenditure than the rest of the Big-6. Or, look at how Arizona State University has managed to increase enrolment (especially of underserved minorities) every year for 20 years all the while becoming more research-intensive and dealing with a seemingly never-ending series of cuts in state appropriations (I’ll be coming back to the ASU case on Wednesday, but for now take a look at the 2022 update on ASU’s Strategic Enterprise Plan for some stats).

I’ll be spending a lot of time over the next few months talking about university (and college) transformations, because I think sharing information about this topic is going to be key to getting us all through this Phase. As someone said at last week’s meeting of HESA’s University Vice-Presidents Network: “No single institution created the current funding model, and no single institution is going to create the next one either. We need to co-operate and share information about our initiatives in order to get to a more sustainable model, faster”.

It’s a whole new game now. The faster everyone gets to terms with the rules, the faster we can shape the new system to the benefit of academia and the country.

Let’s get to it.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

The ASU comparison is good. Impressive and well run public university. It has a commitment to low tuition and is regarded as affordable. Yet in state tuition is over $15,000 CAD per year. More than double many Canadian universities. Places like Ohio State or Penn State are more. Tuition went up a lot at US public’s in the Great Recession fall out, but not in Canada. Domestic tuition in the UK is also about $ 15,000 CAD.. In my dept we can no longer get any where near US salaries to hire research faculty. It used to be – pre COVID – we were maybe 20% below similarly ranked us schools. Now we are more like 40 to 50% below us schools. How can Canadian schools compete without a substantial increase in tuition or gov funding? I don’t see it happening, and fear we will witness a dramatic reduction in quality among Canadian universities. Tuition to me is the elephant in the room that will not be addressed. Any more optimistic voices out there?

Confronted with such an issue some years ago Australian colleges cut teaching staff heavily, and employ many on casual contracts.

Were Australian universities to encounter such an issue they would further increase the proportion of academics they employ only to teach, and increase even more the proportion they employ on casual contracts. The relevant (federal) government would intensify its efforts to restrict research grants to research intensive universities and redesignate some universities as teaching intensive and others as teaching only.

Well, I guess you dropped a hint there. However, if you will indulge me running off on a slightly different tangent here, with a focus on the hot spot Ontario: Ontario universities will have to go “public in name only”. Sooner or later, McMaster and Waterloo and Western and Queen’s and York and Guelph (and whoever else will join) will have to band together and affirm their autonomy. (Would be great to have UofT in there, too. However, their pockets are so deep, they may rather want to sit this out and maybe even “benefit” from a “consolidation” of Ontario universities.)

First, the universities need to increase their domestic tuition rates to realistic market values that allow them to function.

Then, they need to advise Minister Dunlop in no uncertain terms that setting their tuition rates is none of her business. She is still welcome to support their students with the rather small current amount of $X-thousand per year, and decreasing X to X-1 will increase annual tuition by $1,000, while increasing X to X+1 will decrease domestic tuition accordingly, to the benefit of her constituents.

This constant academic “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” policy, for fear of losing the last little shred of support, is becoming ludicrous. If someone is playing hardball with you for such a long time, you better get into the game before it’s too late.

Thanks for the article. I always find these very insightful. Hopefully this will be helpful to steel ourselves for the coming next phase.

Two cents: we’ve been running under a “find efficiencies somewhere” model all through phases 2 and 3 (the past 30 years). I’m skeptical that the solution is to lean harder into that. Related to this, I’m not very enthusiastic about anecdotal evidence from an n=2 (U of Montreal & ASU) that it’s possible to do more with less, if only we do it the right way. A statistician will tell you that if your total n is high enough (n = all North American universities?) you _expect_ a few individuals to buck the real, actual trend, 19 times out of 20 (I’m paraphrasing). If it was that easy then everyone would be doing it, and this thinking distracts from the larger issue: provincial governments (esp. Ontario) continue to and increasingly consider supporting post-secondary education a lower priority.

I know exactly what Ontario’s colleges are going to do: jack up the fees paid by existing and future international students.

There’s no cap on fees charged to international students in Ontario. That was deregulated in the mid-1990s. Further, nothing prevents increasing fees for existing international students, including the 100K+ currently attending the lame duck career college “partner” storefronts in the GTA.

What the Federal rollback/cap really creates is a supply/demand imbalance, and international students who want a “limited availability” spot are going to pay and pay big.

Would anyone expect less from Ontario’s public colleges?

You make the interesting observation that in the “glory days” governments spent 2% of GDP on only 1/3 the number of students. Now they spend about 1.2% on (i.e. only 25% as much per student), with the gap largely filled by sky-high international tuition rates for students from essentially two countries: China (universities) and India (colleges).

The result is that total spending (on a much larger number of students) is about the same as in 1970: 2.5% of GDP. However, Statistics Canada gives the figure 2.9% at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710021101. What’s the reason for this big difference? Is it the inclusion of “post-secondary non-tertiary”?

Also, how much of the “other” is income that can be spent on anything as opposed to endowments, donations etc?