When doing international comparative work in higher education, you’ll realise that the difficulty in comparing systems goes far beyond differences in system architecture and inconsistencies in data. It’s more that there are genuine differences in how some issues are framed.

Take for instance, the issue of equity in admissions. In North America, great positivists that we are, we would measure equity in admissions. Report on them. Try to improve on them. We can see this in the United States all the time. The work of Raj Chetty and other in issuing institutional mobility report cards, College Net’s Social Mobility Index, the new Economic Mobility Index ranking of US universities. (Canada does none of those things because everyone is frightened of accountability and so the easiest way to avoid all the hassle that would go along with measurement is to simply Just Say No. If you think this suggests that we might suck as a country, you would not be far wrong).

But take a look for a second at how Europe thinks about measuring access. Recently, Eurydice (a network of national systems of higher education that exists to explain how education systems are organized and work, sort of like a more effective Council of Ministers of Education, Canada) published Towards Equity and Inclusion in Higher Education in Europe. While Europe still lacks strong comparative and consistent data measuring these elements for a European-wide report, they have at least come up with a decent substitute: instead of looking at outcomes, they look at policies and processes to improve outcomes. If countries have them, they get points; if not, not. Simple.

The report starts from the principle, enshrined in European Union policy, that “the composition of the student body entering, participating in and completing higher education at all levels should reflect the diversity of our populations”. Sounds good. It is also grounded in ten specific principles (edited slightly for length), to wit:

- The social dimension should be central to higher education (HE) strategies at system and institutional level.

- Legal regulations/policies should allow/enable higher education institutions (HEIs) to develop their own strategies to fulfil their public responsibility towards widening access and raising completion rates.

- The entire education system should be made more inclusive by developing coherent policies from ECE through schooling to HE and throughout lifelong learning.

- Reliable data is a necessary precondition for an evidence-based improvement of the social dimension of HE.

- Public authorities should have policies that enable HEIs to ensure effective counselling and guidance for potential and enrolled students in order to widen access and raise completion rates.

- Public authorities should provide sufficient and sustainable funding and financial autonomy to HEIs to enable them to build adequate capacity to embrace diversity and contribute to equity and inclusion in HE (note: this is the one indicator which is mainly quantitative)

- Public authorities should help HEIs to strengthen their capacity to respond to the needs of a more diverse student and staff body and create inclusive learning environments and inclusive institutional cultures.

- International mobility programs in HE should be structured and implemented in a way that foster diversity, equity and inclusion and should particularly foster participation of students and staff from vulnerable, disadvantaged or underrepresented backgrounds.

- HEIs should ensure that community engagement in HE promotes diversity, equity and inclusion.

- Public authorities should engage in a policy dialogue with HEIs and other relevant stakeholders about how the above principles and guidelines can be translated and implemented.

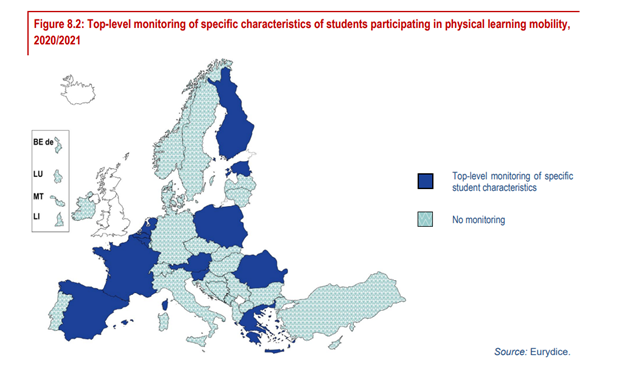

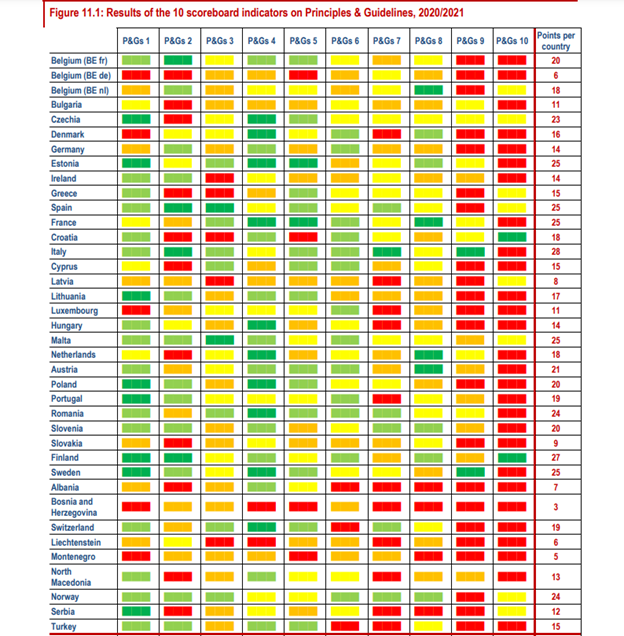

Now the great thing about this Eurydice report is that it finds multiple metrics to examine whether each member country is living up to these ten principles and awards scores to each country on the basis of these metrics (countries agreeing to be scored this way is *really* something Canadian provinces would never allow CMEC to do). So, for example for principle #8 on international mobility, it asks five questions: a) are national mobility policies focused on students with specific characteristics (i.e. under-represented students), b) do countries have a statistics monitoring system to identify underrepresented students participating in mobility schemes c) are grants portable to other countries, d) are there specific measures in place in institutions to support underrepresented student in mobility programs and e) do top-level national authorities advise and support higher education institutions on the use of new technologies in teaching and learning?. What you end up with is a set of 40+ indicators where every country in Eurydice can be compared like so:

Also, at the end of the document, there is something which is not quite league table/ranking of countries, but something that could become one easily.

There are some difficulties with an approach which awards points for adopting policies and procedures rather than for actual outcomes. I mean, putting Italy at the top of a list for widening participation is preposterous. And from a North American perspective, many of the indicators make almost no sense because they assume a more statist approach to higher education than we would ever consider (points for having policies where the government gives instruction to institutions on how to deliver mental health services is or keep abreast of new teaching technologies seems hilarious in North America, because few believes government is really qualified to advise institutions on either subject)

But still, if you want an interesting thought experiment, read the report and mentally score your province on the 40-odd indicators. My guess is most provinces would score in the bottom half of this ranking and some would not hit double-digits. And the reason for this is simply that the emphasis here is really on whether or not government has the ability to plan/steer a system, and collect data appropriate to its goals. What this exercise rewards is state capacity in planning/managing higher education. And even allowing for the fact that in North America we don’t expect the state to manage/plan quite as much of the higher education system as Europeans do, it’s still sobering to realize how weak Canadian state capacity is when it comes to higher education.

Our provinces – even our smaller ones – should be capable of operating at levels similar to Lithuania or Estonia. But do they? Decide for yourself after scanning the report, but I have my doubts.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post