If you’ve ever spent any time looking at the literature on private higher education around the world – from the World Bank, say, or the good folks at SUNY Albany who run the Program for Research on Private Higher Education (PROPHE) shop – you’ll know that private higher education is often referred to as “demand-absorbing”; that is, when the public sector is tapped-out and, for structural reasons (read: government underfunding, unwillingness to charge tuition), can’t expand, private higher education comes to the rescue.

To readers who haven’t read such literature: in most of the world, there is such a thing as “private higher education”. For the most part, these institutions don’t look like US private colleges in that (with the exception of a few schools in Japan, and maybe Thailand) they tend not to be very prestigious. But they aren’t all bottom-feeding for-profits, either. In fact, for-profits are fairly rare. Yes, there are outfits like Laureate with chains of universities around the world, but most privates have either been setup by academics who didn’t want to work in the state system (usually the case in East-central Europe) or are religious institutions trying to do something for their community (the case in most of Africa).

Anyways, privates as “demand-absorbers” – that’s still the case in Africa and parts of Asia. But what’s interesting is what’s happening as to private education in countries heading into demographic decline, such as those in East-central Europe. There, it’s quite a different story.

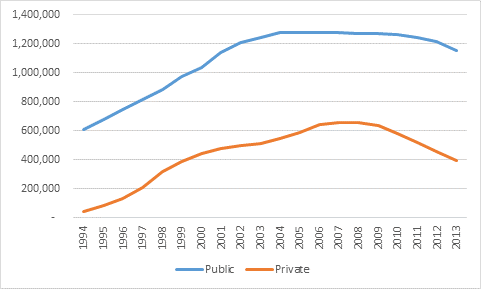

Let’s start with Poland, which is probably the country in the region that got private education regulation the least wrong. There was a massive explosion of participation in Poland after the end of socialism, and not all of it could be handled by the private sector, even if they could charge tuition fees (which they sort of did, and sort of didn’t). The private sector went from almost nothing in the mid-90s to over 650,000 students by 2007. But since then, private enrolments have been in free-fall. Overall, enrolments are down by 20%, or close to 400,000 students. But that drop has been very unequally distributed: in public universities the drop was 10%; in privates, it was 40%.

Tertiary Enrolments by Sector, Poland, 1994-2013

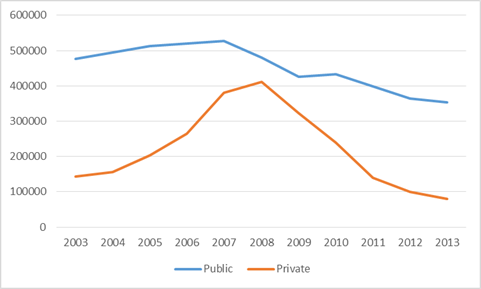

In Romania, the big picture story is the same as in Poland, but as always, once you get into the details it’s a bit more on the crazy side – this is Romania, that’s the way it is. Most of the rise in private enrolments from 2003 to 2008 was due to a single institution named Spiru Haret (after a great 19th century educational reformer), which eventually came to have 311,000 students, or over a third of the entire country’s enrolment.

Eventually – this is Romania, these things take time – it occurred to people in the quality assurance agency that perhaps Spiru Haret was closer to a degree mill than an actual university; they started cracking down on the institution, and enrolments plummeted. And all this was happening at the same time as: i) the country was undergoing a huge demographic shift (abortion was illegal under Ceausescu, so in 1990 the birthrate fell by a third, which began to affect university enrolments in 2008); and, ii) the national pass-rate on the baccalaureate (which governs entrance to university) was halved through a combination of a tougher exam and stricter anti-cheating provisions (which I described back here). Anyways, the upshot of all this is that while public universities have lost a third of their peak enrolments, private universities have lost over 80% of theirs.

Tertiary Enrolments by Sector, Romania, 2003-2013

There’s a lesson here: just as private universities expanded quickly when demand was growing, they can contract quickly as demand shrinks. The fact of the matter is that with only a few exceptions, they are low-prestige institutions and, given the chance, students will pick high-prestige institutions over low-prestige ones most of the time. So as overall demand falls, demand at low-prestige institutions falls more quickly. And when that happens, private institutions get run over.

So maybe it’s time to rethink our view of private institutions as demand-absorbing institutions. They are actually more like sponges: they do absorb, but they can be wrung out to dry when their absorptive capacities are no longer required.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post