It was released yesterday. And it’s godawful.

It’s a thirty-page document, but minus the cover page, colophon, table of contents, introduction, twelve pages of fact sheets, and another four pages to describe previous consultations and provide global context, it’s really just ten. Of these ten, roughly half describes initiatives the government has already undertaken, (existing scholarship programs, Mitacs funding, etc). So, then, five pages, maybe. Part of this is spent re-hashing lines about Canada’s “brilliant” reputation for international education – a claim which their own research says is utterly false (see: this previous post on DFAIT’s brand research).

In those five pages, the Government of Canada makes specific commitments to:

- Spend $5 million to give Canada a re-brand. And do a bunch of stuff already announced in the last budget

- Consult regularly with stakeholders

- Establish a Trade Commissioner presence within the Canadian Consortium on International Education to “co-ordinate efforts” (to what end is not stated)

- Support an event management system to better co-ordinate events held by stakeholders.

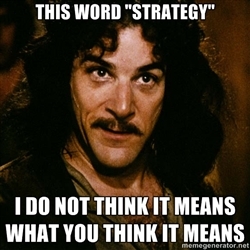

That’s it. That’s the entirety of the strategy’s commitments. There are some additional words in there that talk about “developing the export of education know-how… by supporting marketing efforts of Canadian stakeholders”, but it’s all vague, meaningless guff.

Amazingly, the document sets no real goals for the government. It sets targets for other people (e.g. doubling the number of foreign students by 2022), but that’s not the same thing. There’s no rationale for such numbers as are in the strategy, and the activities in the strategy are not linked to intended outcomes in any way. Similarly, although the document talks about focussing efforts on selected certain foreign markets, these markets turn out to be India, China, Brazil, the entire friggin’ Middle East/North Africa region, Mexico, and Vietnam. The rationale for the last two are mysterious; the first four contain half the world’s population. That’s some focus.

Towards the end of the document, the government informs us gravely that it will be monitoring effectiveness, and putting performance measures in place – checking whether their “inputs” (spending 5 million bucks on a brand, and doing some consultations) are producing the appropriate “outputs” (265,000 more international students by 2022, a greater proportion of whom choose to stay here after studying). When I say it is laughable, I am not using a figure of speech. Honestly, I haven’t laughed so hard in weeks.

This “strategy”, if we can call it that, is without question the most thorough and comprehensive argument for why the Government of Canada should stay the hell out of higher education. It is shallow. It is abject. It shows no sign of being the product of discussion with either the provinces, who are responsible for education in this country, or the colleges & universities who deliver it. It does not articulate problems well. It does not focus resources in a meaningful way, nor are the investments it lists in any way proportionate to what few goals it does set out.

In short, if one is left with any thought at all about this document, it is this:

Canada, as a country, can and should do better than this.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

That document was, by turns, mush and glitter, possibly a political posture document. It is about as clear as reading uni-level strategic planning docs that never make clear precisely *why* the big mad rush to stuff our campuses with as many international students as will fit. Of course, cynical mini-me says that it is about collecting the higher international student tuition, and bolstering softening enrolments, but the first is easily circumvented with a cute little trick: send junior to Canada for just long enough to attend high school and gain residency, and junior can pay the same tuition as the domestic students. But that’s cynical mini-me.

And how do they calculate that all these int’l students will not just take the credential and leave? Because Canada is some inarguably awesome paradise on earth where six figure jobs are on every gold-paved street corner?

I am reminded of the Soviet planned economy model here for some reason. In the sixties, they gradually came round to the realization that their “growth” measured as net material product output was strong, but that the gov’t input as investment was higher than those outputs. About 5% additional input resulted in about 3% ROI. Now, 5 million federal bucks is not even the whole picture of the “input” value when you also compute the other int’lization inputs by individual universities combined.

Now there is a good research question for you, Alex: precisely how much are all the proselytizers of internationalization – from uni operating budgets to all levels of gov’t – pumping into this scheme? Match that to a best guesstimate of what the “output” value would realistically be and see if the scheme will turn out in the financial black or the red.

The word “strategy” should be banned from the entire sector period. Neither universities nor governments are using it properly.

There are also a lot of hidden costs to this strategy for those of us on the front lines actually teaching these students. My cynical side thinks that a bunch of people will get some really nice recruiting trips out of this, as well as some more $ to keep university budgets in good shape, but what about the program delivery side of things? I am all for having more international students for all the reasons usually cited, but too many change that way that courses are delivered and this may be a disservice to Canadian students. Often foreign students come in unprepared for the culture of Canadian universities and lack the language skills necessary to succeed. They avoid the critical thinking classes and head straight for the technical classes. As such, we might also be doing the international students a disservice by not giving them a true “Canadian” education.

The countries that are targeted are also very aggressively developing their own systems of higher education and so, at best, we might see a temporary increase in international students until the new systems have matured.

Me thinks that this is simply another part of Canada’s immigration policy, rather than a national education policy.

If it were part of an immigration strategy, you;d expect to see a theory of how students become immigrants and some actions targeted at improving that transfer rate. Nothing like that in sight.

Who says they are being transparent?

The choice of program also has an impact on how “profitable” international students actually are for an institution. In many ways the concept that international students represent a huge profit for institutions is a myth, especially at the graduate level. At least in Ontario, the forgone revenue from the provincial government (BIUs) is almost equivalent to the premium on international fees.

If all our international students were History undergrads, the myth would hold true. For Engineering grad students, on the other hand, the difference in income for the institution can be as little as a few hundred dollars.

What bothered me (among other things) in this document was the implication that the benefits from international students were evenly spread, despite the well-documented fact that the vast majority of these students are being drawn to institutions clustered around Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. At least in the GTA, the provincial government is also pressuring institutions to increase capacity for the growing local population