Last week, Yukon Education Minister Doug Graham announced that the territory was going to change the name of Yukon College to Yukon University. The College then proceeded to state that it would launch new degree programs and seek membership in Universities Canada in 2017.

Well, now. How is that going to work exactly?

Universities Canada has some pretty clear guidelines about membership. Point 4 says that a prospective member must have “… as its core teaching mission the provision of education of university standard with the majority of its programs at that level”. At the moment, only five of Yukon College’s fifty-odd programs are at degree level (Social Work, Public Administration, Environmental and Conservation Sciences, Education – Yukon Native Teacher, and Circumpolar Studies). Now, presumably it could upgrade some of its career & tech programming into full degree programs to change the balance a bit, but it’s not clear that would be to students’ benefit: there are good reasons – cost among them – to keep programs like business administration, early childhood education, and various technologist programs at two years rather than four.

One possible solution would be to split the administration of the college and the university, so that the two could share physical space, infrastructure, and back-office functions, while at the same time having separate management and programming. This might get Yukon College off one hook, but it would quickly get snagged by another. Universities Canada also requires prospective members to have 500 FTEs for at least two years before joining.

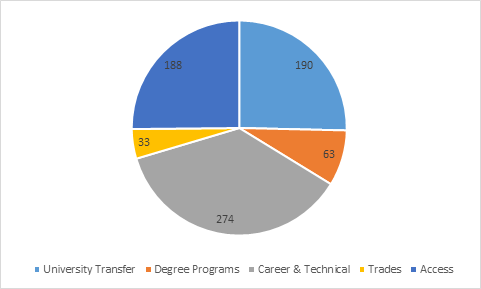

In terms of student numbers, Yukon college looks like this:

Yukon College FTE Students by Stream, 2012-13 (Yukon College Annual Report 2013-14, FTE = FT + [PT/3.5])

Degree and transfer programs together only make up 253 FTEs, or about a third of the college’s 748 FTE students in credit programming. One would need some really big increases in student numbers to change this. But Yukon College would likely have trouble moving the needle much. Here’s the history of Yukon College enrolments:

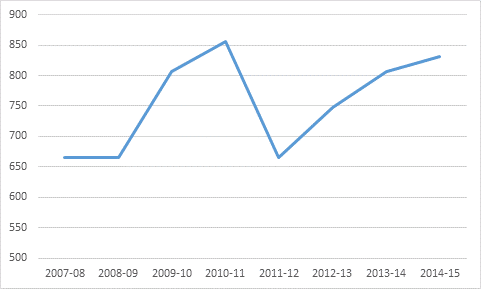

Total FTE Enrolments at Yukon College, 2007-08 to 2014-15

Numbers at the college have never gone over 850, and the highest two-year average is about 820. Even assuming you could nudge university numbers from a third to a half of total enrolments, that would still leave a newly-separated university nearly 100 students shy of the required 500.

Now, there’s nothing stopping a Yukon institution from using the name “university”, even if Universities Canada doesn’t agree. Quest University seems to be doing fine without Universities Canada membership, for instance. But Universities Canada is still the closest thing Canada has to an accreditation system, and so being on the outside would hurt.

But here’s a wild-and-crazy suggestion: Yukon wants a university; Nunavut wants a university; presumably, at some point, the Northwest Territories will glom onto this idea and want a university, too. Any one of them, individually, would have a hard go of making a serious university work. But together, they might have a shot.

Of course, universities are to some extent local vanity projects. I’m sure each territory would prefer its own university rather than share one. But these things cost money, especially at low volume. We could have three weak northern universities, or we could have one serious University of the North. Territories need to choose carefully, here.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Alex Usher has proposed an interesting model for how Yukon College should become a university. I would like to suggest a different model.

I should disclose that my wife and I own a little house in Whitehorse where we spend as much time as we can. (Long story.) I do not have any clients in Northern Canada.

The challenge in creating a university with campuses in each of the three territories, as Alex proposes, is that transportation links across the territories are almost non-existent.

From Whitehorse to Yellowknife there are two commercial flights a week. From Whitehorse to Iqaluit, the best options involve staying overnight in Yellowknife or Ottawa. You don’t want to ask about costs.

By contrast, there are several commercial flights daily from Whitehorse to Vancouver, and the flight time is less than from Toronto to Winnipeg. There are also several flights a week from Whitehorse to Edmonton and Calgary.

With no real opportunities for faculty, administrators or students to travel from one campus to another, an all-Northern university would need to rely on virtual connections. There is nothing wrong with that, but there is no inherent reason to prefer an all-Northern virtual collaboration to a North-South collaboration.

The reality is that the territories are at different stages of postsecondary development. The 2011 National Household Survey found that the Yukon had 110 PhDs and 1,346 Master’s degree-holders. The Northwest Territories had slightly fewer. Nunavut had about one-third as many. The 2006 Census showed a similar pattern.

Yukon College has earned more than $4 million in sponsored research funding in each of the past two years, placing it among the top 14 colleges in Canada. The colleges in the other territories each have research strengths, but their sponsored research funding does not place them in the top 50.

Given its circumstances, Yukon College might give serious consideration to a North-South collaboration, by finding a university partner in southern Canada that would be an academic sponsor in the new university’s early years. The University of Toronto played this role for York University in the early 1960s. Student numbers will improve as students see that the new university fully meets the academic standards of a well-established institution.

Yes, creating a new university from a small college is a challenge. But some of Canada’s universities started with fewer strengths than Yukon College has today. With well-chosen collaborations, there is real potential to establish a specialized university that serves its community and creates new knowledge about the environment and culture of the North.