Every once in awhile, you’ll hear folks talking about the scourge of youth unemployment. If you’re really lucky, you’ll hear them describe it as a “crisis”. But how bad is youth unemployment, really?

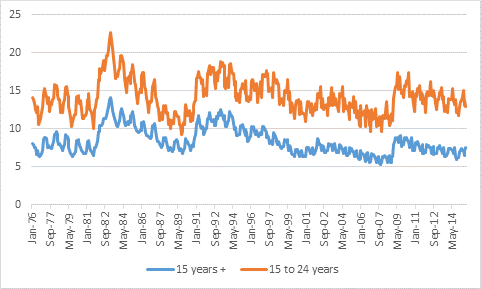

Well, the quick answer is that you can’t really separate youth unemployment from general unemployment. As Figure 1 shows, one is a function of the other.

Figure 1: Youth Unemployment Rates, 15 and Over vs. 15-24 Age Groups, Canada, 1976-2015 (Source: CANSIM 282-001. Seasonlly-Adjusted)

As Figure 1 also shows, compared to most of the last 40 years, youth unemployment is currently fairly low. In the 476 months since the Labour Force Survey began, it has been lower than it is today only 29% of the time. If this is a crisis, it is of exceedingly long duration.

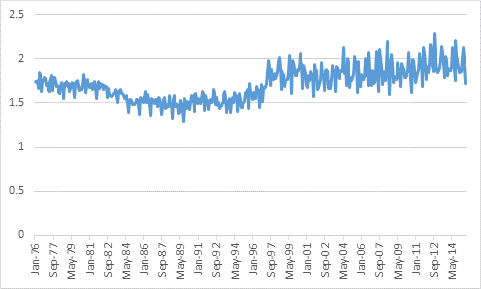

Now, what some people get upset about is the fact that youth unemployment is “twice the overall rate”. But is that really historically unique? Figure 2 shows the answer.

Figure 2: Ratio of 15-24 Unemployment Rate to 15 and Over Unemployment Rate (Source: CANSIM 282-001)

So, there are two things here on which to remark. The first is that 2:1 isn’t an immutable ratio: it has changed over time, most notably in the mid-90s when it increased significantly. The second thing is that the ratio is a lot more seasonal than it used to be. It’s not entirely clear why this happened. I had thought initially that it might have something to do with increasing PSE participation rates, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. A mystery worth pursuing, at any rate.

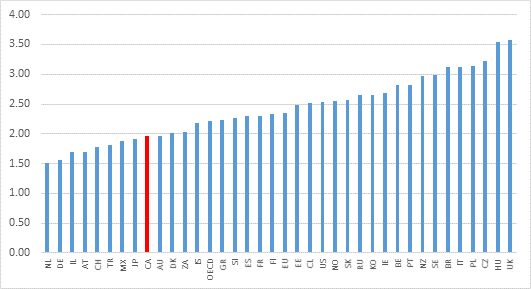

In any case, we should also ask: how does Canada look in comparison to other countries? In Figure 3, I show the ratio of youth unemployment to overall unemployment in various countries. Canada’s current ratio – about 1.96 – is not world-beating, but significantly better than the OECD average (2.2). It suggests that the question of youth employment ratios is actually something all economies – with the exception of the Netherlands and Germany, perhaps – deal with.

Figure 3: Ratio of Youth Unemployment Rate to Overall Unemployment Rate, Selected Countries (Source: OECD)

To get right down to brass tacks: workers gain value with experience. By definition then, young workers are, on average, less valuable than older workers. This is the reason why they have trouble getting hired. And this is why, in the end, the only way to bring down youth unemployment is to give them more value to employers; which is to say, they need more job-ready skills.

Could we do better than we are doing? Yes, of course. But even the best countries in the world aren’t doing much better than we are. So, let’s work on this problem, but maybe tone down the rhetoric about the its extent.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Hi Alex,

Thanks for this, it is very useful. In terms of the seasonality, I once asked Statistics Canada if a high school/university student looking for a job in the summer could be considered unemployed. I think I got three different answers, one of which was that if they were looking for a job they would be counted as unemployed.

I get frustrated with commentaries like this that don’t parse out the quality of employment on offer, and fall back onto the “skills/experience deficit” to justify the glut of crappy, insecure jobs that people — sometimes very well educated people — earn a living from. I don’t know that anyone would argue that young adults have somewhat less value due to inexperience, but the whole “skills deficit” argument is just a convenient excuse for employers to avoid any long-term or principled commitment to their workers. Paid internships at least offer young adults the opportunity to gain experience, but there’s a whole lot of exploitation out there justified by the “lack of job ready skills.”

One big reason for the trend line in figure 2 would I think be the weight of the 15-24 group in the overall numbers.

The value of the comments is quite clear, particularly as they provide an antidote to the old chestnuts dragged out in the original post. Hands up all those who want to earn a living by working part-time at McDonald’s!

It is much more useful to track the (relatively) high wage, stable employment some younger workers undertake. Apprentices do pretty well, and from time to time various ministers urge the post-secondary institutions to produce more training like the apprentice programs. Those officials are so badly informed that they do not realize that the crucial sequence in apprenticeship is employment first, then training. More useful change will come from tracking and emulating what works.