Governments love to talk about STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) programs. They were given prominent space in the last Canadian federal budget, and the acronym permeates U.S. educational policy discourse. It’s conventional wisdom that increasing the number of STEM graduates is essential to economic growth. You might think that the chief purpose of the modern post-secondary institution is to churn out graduates in STEM fields – and that as a corollary, arts students are some sort of vestigial leftover from a bygone era, kept around only to avoid the pain of their excision.

The full-court press to jack up STEM graduate production rates overlooks one important detail – the STEM fields are hardly a monolith, and there are some very important differences among them. Indeed, sometimes it’s unclear why these fields are grouped together at all. The issue, in large part, lies with the “S” – an undergraduate science degree is much less likely to get you a job.

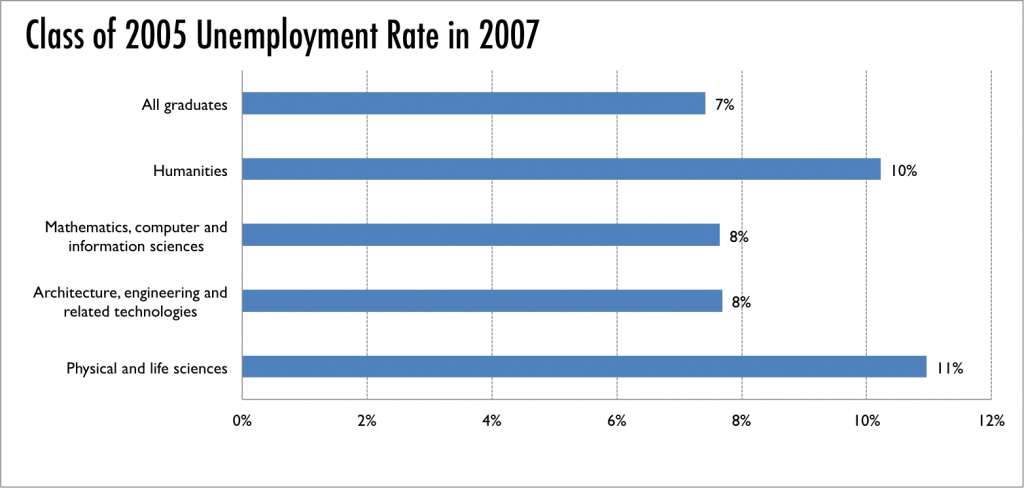

Take a look at labour force status of the class of 2005 two years after graduation, courtesy of Statistics Canada’s 2007 National Graduates Survey. For comparison, we’ve left in data for the humanities – a field that is seldom lauded as the ticket to immediate success in the job market.

It becomes quickly apparent that one of the STEM fields is not like the others. Graduates in the physical and life sciences have extremely low employment. Barely half of them have a full-time job, only two-thirds are employed at all, and almost a quarter are not in the labour force – two years after graduating. Moreover, they have the highest rate of unemployment (11%). Students in engineering or math and computer science, by contrast, have full-time employment rates of around 80% and employment rates around 85%, with unemployment under 8%. Based on short-term employment outcomes, the sciences have little in common with the other three. It makes you wonder: if “TEM” sounded half as good as “STEM,” would we be so quick to lump in the sciences with the rest?

Of course, the sciences still offer great value to their students and society – even if that value doesn’t pay off as employment in the short term. And should science’s showing on these graphs make it feel lonely, there’s another field that might be its friend. As the data shows, a science student’s employment prospects are rather similar to those of a humanities graduate. And that’s something we shouldn’t hide behind an acronym.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One response to “Why is there an “S” in STEM?”