Yesterday, we discussed why student debt burdens were falling. One of the key ingredients in that recipe was that student debt had remained stable, or even fallen, over the last decade or so. This is a puzzling piece for many because it seems counterintuitive. So what’s going on?

Well, costs are increasing, but only modestly so: since 2000, tuition has only been rising about 2% above inflation. There’s been no real change in the percentage of students living away from home – and for those who do live away from home, the picture is mixed: students in Western Canada are paying a lot more than they did 10 years ago; students in Ontario, on the whole, tend to be paying less. Nationally, it mostly evens out. Given these changes in costs, one would expect modest but noticeable increases in borrowing, ceteris paribus. So something else must have changed in order to offset this. But what?

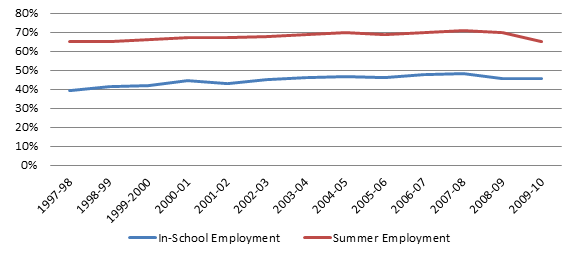

Is it a question of students themselves having more resources? Probably not. As Figure 1 shows, student employment is remarkably stable over time. So, too, is their average hourly income from wages, which surveys show is almost always 20-30% above minimum wage.

Figure 1: Student Employment Patterns, Canada, 1997-8 to 2009-10

What about money from parents? This seems to be up a little bit: average transfer in 2001-2 was about $2000 (in $2011), and is now about $2500. What has changed, however, is the amount of money students get through RESPs. This was negligible ten years ago; now, roughly 30% of students receive money from this source, and it’s a significant amount, too ($4,000/year, on average). Obviously, much of that’s going to students who aren’t on student aid, but for those who are, it’s more than enough to explain the slowing rise in debt.

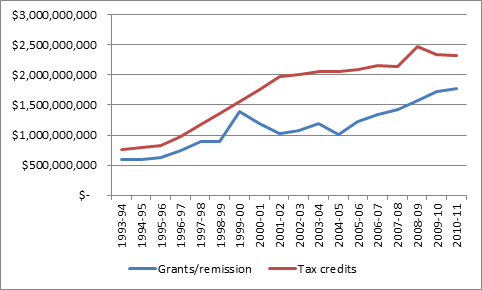

Then there’s the rise in student assistance. Institutions have massively increased their scholarship budgets. In the 1990s, about one in three new students got some kind of entrance scholarship. Now it’s two in three. The total amount spent on grants and remissions by provincial and federal governments jumped from $600 million/year in 1995, to almost $1.8 billion in 2010 (both figures in $2011 real dollars). And of course, governments have added an extra $1.5 billion in tax credits. Not all of that ends up in students’ pockets (some ends up with parents, some gets deferred until after graduation), but enough does to take a bite out of rising costs.

Figure 2: Increases in Total Government Student Assistance, Canada, 1993-94 to 2010-11 (in real $2011)

None of these, on its own, amounts to a silver bullet to explain why student debt is stable or falling. But together, it’s easy to see: more grants, more tax credits, the creation of the RESP are, together, probably putting about $3 billion extra into students’ hands every year. Call it about $3,000 per year, per student. Then add institutional aid, and throw in the extra billion or so that has gone to grad student funding in the past fifteen years. That brings us to about $4,000 extra, per student. That’s more than enough to explain why debt isn’t increasing.

In fact, the real question may be: why hasn’t it decreased more?

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Any sense as to how uniform these patterns are across the country? I know Atlantic Canada has significantly higher average debt and a higher percentage graduating with debt, but has that consistently been the case?

Hi Jim. Thanks for writing.

As far as I;ve been watching this stuff, yeah, that’s been the case. Don’t know the 86 data particulalry well, could go back and check – but otherwise, for Atl Canada, assume avg debt is about 5K over national avg and incidence of debt is 10 percentage points higher.

How would you assess the additional debt some student loan borrowers take on through lines of credit from financial institutions?

Hasn’t changed much in the last decade: https://higheredstrategy.com/the-curious-case-of-disappearing-student-debt/

If average student debt is holding steady or going down, and largely as a result of the factors you’ve outlined, does this mean that student debt is becoming more unequal, with far more of it being carried by students without access to RESPs, parental aid and scholarships?