Before Christmas, I made a bit of a fuss about the six Ontario Colleges who had made deals with private career colleges in the GTA to teach international students. The previous provincial government had decided to shut these agreements down because they seemed to pose systemic reputation risks to Ontario colleges, but the new one decided not only to leave them alone but to allow those colleges to double down on them, ostensibly on the grounds that they all really, really needed the money. I decided to find out if that were true by looking at the colleges’ latest financial statements. And, you know, wow.

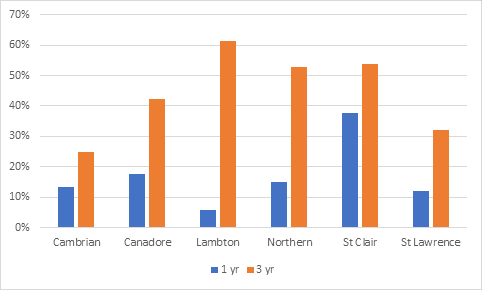

Figure 1: Increase in Revenues, Ontario Colleges with GTA satellite campuses, 2018-19 vs 2017-18 and 2015-6

All but one of the six colleges saw an increase in total revenues of over 10% in 2018-19. Not tuition revenues; total revenues. Increases in tuition revenues varied, but in at least one case the increase was over 50%. In one year. Over three years, three of the colleges saw increases in revenues of over 50%. Yes: Five. Zero. And yes, it’s basically all international student revenue.

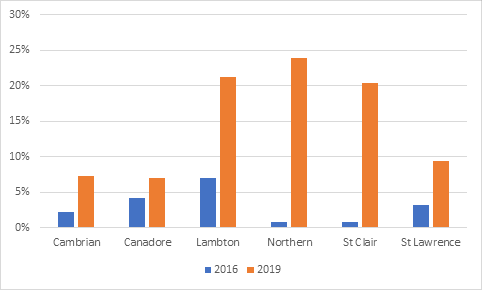

And keep in mind, this is just revenue. If we look instead at net revenue – that is, revenue minus cost, or what we would call profit if these weren’t public institutions – you see something even more staggering. Some of these institutions now have net revenue figures of over 25%. Which is up there with the casino industry for sheer margins.

Figure 2: Net revenues as a percentage of total revenues, Ontario Colleges with GTA satellite campuses, 2016 vs 2019

Wild, huh? But of course, in order to demonstrate exactly how wild this is, I need control group. So, I selected six similar colleges, all outside Toronto, which did not have GTA satellite campuses. Because those schools don’t have the same opportunities to make out like bandits and are probably much poorer and…wait, what?

Figure 3: Increase in Revenues, Ontario Colleges without GTA satellite campuses, 2018-19 vs 2017-18 and 2015-6

This is not what I was expecting. Turns out that, at least in 2018-19, all these schools also made out like bandits on international student tuition, even without dodgy arrangements with private vocational colleges. In fact, across these control-group schools, the average one-year increase in revenues was 22%, compared to just 18% for the dodgy colleges group (the first group still did better over three years, 44% to 35%, and the control group’s “net revenues” averaged just 10% in 2019, compared to 15% for the satellite campus group).

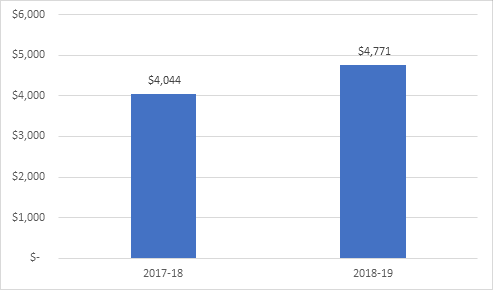

So, I take the final step and ask myself – what happened at the other twelve colleges? Exactly how much did the system as a whole make last year? I couldn’t quite get the full system because Humber appears not to have put its financial statements on the web yet, but other than that the data is complete. And here’s the low-down: system-wide, total income in 2018-19 rose from a little over $4.04 billion the previous year, to $4.77 billion. That is an 18% increase. One. Eight. By far the largest single-year increase in revenues in the system’s history. Ever. Only two colleges (Lambton and Niagara) saw increases of less than ten percent, while four – Centennial, Conestoga, Confederation and Sault, saw one-year increases of over 25%. And as nearly all of it came from international student tuition.

Figure 4: Total Revenues in Millions, Ontario College System (ex-Humber), 2017-18 and 2018-19

My jaw is still on the floor. This can’t possibly end well.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Alex, you might enjoy the analysis of Australia’s experiences with the financial impact of international students – in particular, the report by the Nous consulting group on “what might happen if the tap runs dry” https://www.nousgroup.com/insights/international-higher-education-tap-at-risk-of-running-dry/. They highlight the difference in institutional approaches between those who have used revenue from international students to “turn on the taps” versus those who have used the revenue to “dig deeper wells”…Tom Carey

Smart and timely analysis. Some further thoughts. First, the analysis should motivate the government to review and reset the Small, Northern, and Regional grant program. The program is based on a population density and economy scale model that, for those SNR-eligible colleges with satellite campuses, is seriously out of date. Taken one step further, the HESA analysis would indicate the extent to which additional satellite campus revenue has already defeated the economy of scale argument. The previous government had chances to do this in the 2016 formula funding consultation, and, again, in response to the 2017 special advisors’ report on International Postsecondary Education. The current government, which in other areas has expressed concern about double-dipping, seems to be willfully ignorant of the connection between its policy on Public College-Private Partnerships Policy and the SNR grant program. Second, the reported increases in revenue may be having an effect on the colleges’ reserve funds, leading to a question about whether all the net revenue is actually being spent on the operational costs of delivering programs.Third, maybe it is time to revisit the “visa pool” model for colleges.