The province decided to release the report of its Blue Ribbon Panel on Post-Secondary Education Financial Sustainability last Wednesday. Remember, this was a report commissioned by the provincial government in response to a pair of reports from the Auditor-General, one on Laurentian University and another on other smaller institutions in November 2022. It’s not what I would call an ambitious document; the panel’s terms of reference instructed that any recommendations “be considered through the lens of fiscally responsible and affordable actions”, so by necessity a lot of the calls to action are small beer. It is, however, a serious document and well worth an examination.

So let’s dive in! For simplicity, I’ll divide the discussion into four sections: the Revenue Discussion, The Savings Discussion, The Miscellany and the Government’s Response to the report.

The Revenue Discussion

The panel goes some distance to describe the problem of underfunding, albeit in a more understated manner than most people in the sector would have done. The big recommendations are:

- The Government should immediately raise its grants to institutions by 10%, and then increase by inflation or 2% for the next three years thereafter (the actual value of this will vary a bit depending on what inflation will be).

- Tuition should rise by 5% immediately, and then increase by inflation or 2% for the next three years thereafter. For professional and in-demand programs, the immediate hike should be 8%. (the panel also claims that college fees should rise even faster because domestic fees are lower than the national average…but this is hard to verify since there is no publicly-available national tuition fee data for colleges, only an annual and secret survey of provincial “base” fees done by the provinces which, I suspect, does not have much to do with “averages”).

- To offset the increase in tuition fees, Student Financial Aid rules should be amended in a variety of ways. The panel offered a variety of potential rule changes, some good (eliminating the requirement that a minimum of 10% of aid come in the form of a loan), some not so good (eliminating interest on loans).

It’s not clear how much the third point would cost (mainly because it’s not clear which of these options might be taken up). But the financial effects of points one and two are reasonably easy to work out.

Here’s what the impact of point 1 looks like, assuming (optimistically) that inflation stays at 3% for another year and then drops to 2%. That 10% increase only ends up being a 7% boost after inflation: equal to about $450 million, split roughly 66-34 in favour of universities. As shown in Figure 1, that would bring public funding back up to about where it was two years ago. It would still be 12-13% lower in real terms than it was when the Ford government took office. If the government pursues this path, institutions will find it helpful, just not especially so.

Figure 1: Projected Public Subsidies to Ontario Institutions by Type, if Panel Recommendations are Accepted, in Billions of $2023, 2001-02 to 2026-27

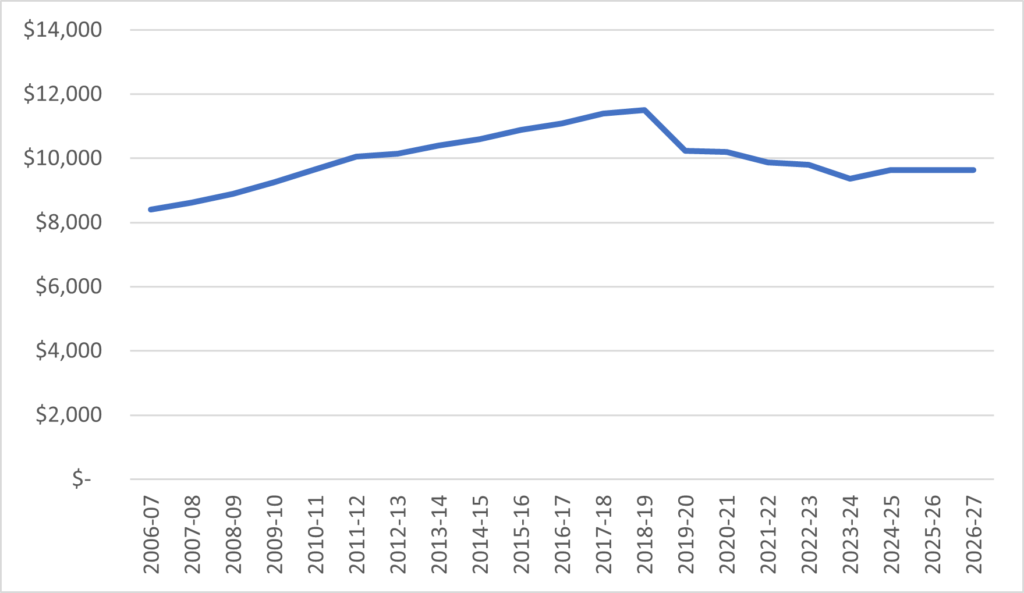

As for point two, a 5% increase in tuition for most undergraduate programs plus 8% for professional/in-demand probably means about a 6% increase overall. But, assuming 3% inflation next year, then this increase is just 3% in real terms. And it will leave tuition 16% lower, in real terms, then it was in 2018 when the government took office. Again, any help will be welcome, but any impact will be limited.

Figure 2: Projected Average Undergraduate Tuition Fees, Ontario, if Panel Recommendations are Accepted, in $2023, 2006-07 to 2026-27

The report also contains a lot of talk about altering the funding formula to shift the distribution of funds within the envelope. This does not make a difference to the overall financial state of the sector, but it could be that certain types of alterations would make a difference to some smaller institutions. However, the level of detail at which this is discussed in the paper itself makes it somewhat unclear which institutions would benefit from these kinds of proposed changes.

The Savings Discussion

The Terms of Reference directed the panel to look at ways to make universities more cost-effective. This was a difficult ask, since cost-efficiency is notoriously hard to measure in education (if you can’t define quality, and the most common quality metric is how much money you spend, then by definition cost-efficiency can’t exist!) and it’s not like the panel was given any resources for research. In the absence of any research budget it seems the best they could do was to talk to consultants who specialize in reducing labour costs in universities; specifically, the Nous Group (whose work I looked at back here). The gist of what Nous told them was “there is room for efficiencies at universities” which…you know, no kidding. Specifically, the major duplications of effort at the central and faculty levels over the last couple of decades could be undone (U of T probably doesn’t need twelve registrars or however many it has – but then again U of T isn’t exactly hurting for cash). But that’s more of a big university thing than a small or medium-university thing and while Nous has plenty of experience with big universities, it’s not clear how well the lessons of those institutions transfer to smaller schools. And while the panel did point to interesting cost-savings consortia for small schools in the US (Claremont College Services, Five Colleges Incorporated), it is worth noting that they all to some degree depend on mutual proximity, which is not something that, say, Windsor, OCADU and Lakehead possess.

Kudos to the panel, though, for making the point that Ontario’s universities already have the country’s lowest salary and benefits costs per FTE of any province, which is largely a function of economies of scale at Ontario’s many mega-universities. I doubt the Government will mentally take this on board, but glad the panel made the point anyway.

The Miscellany.

The panel was asked to pronounce on a whole bunch of things not entirely related to financial sustainability. These included:

- What the heck do we do with French language universities in Ontario? I posed that question a few weeks ago back here: the panel framed the issue in similar ways (and indeed one of its three options is darn near word-for-word what I suggested). But it did not, in the end, answer the question definitively, instead providing the government with three options.

- What about International students? As you would expect from a report that has minimizing growth in public expenditures as part of its terms of reference, this report does not recommend a retreat from international enrolments. It does, however, suggest – rather too politely, in my view – that the province enforce its Ministerial directives and start talking to institutions in advance about their future plans.

- A whole chunk of stuff around research, data (big shock – it’s terrible), Indigenous institutes, student supports, the higher costs of northern institutions…too much to summarize really, but do read the document if any of this is of interest.

- The chair of the panel made an interesting plea for treating U of T differently from the rest of the system on the grounds that it is a genuinely unique institution which continues to carry the lion’s share of the load on research and graduate studies in this province. I think it’s an interesting question worth debating (Canada does not think enough about what matters to flagship institutions) but while the other panel members plainly disagreed with this notion, the group unfortunately chose not to print any counter-arguments.

The Government Response

Given that the Government has had a copy of the report in its hands for about three months, it chose not to publish a response to it at the time of its release last week. Instead what we got was this press release, which ignored everything about the call for greater public funding and basically said “thanks for the report, glad to hear about all the possible efficiencies.”

For the government not to have any policy response to the only serious external review in the past six years is utterly inexcusable. There are a variety of explanations for this behaviour and I am not sure which is worse. One possibility is that the government is content with the status quo, has no intention of responding to the report, and only commissioned the report to get the AG off its back. Another is that it is desperately desirous of change but is simply incapable of coming up with a coherent response within three months, either because the department itself is operationally dysfunctional, or because it doesn’t have enough heft to get the Premier’s office to sign off on anything substantive. Presumably we will find out more between now and the provincial budget, but I have to say things do not look promising.

The one thing that the Government cannot say from this point forth, though: the next time a Laurentian happens (and I’ve been told by a few people that one institution came very close to not making payroll this spring), it cannot say that it wasn’t warned. For that alone, the Panel report is a welcome document.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

There is little discussion of the large scale over-building at Ontario colleges and universities over the last decade. These facilities are now way beyond the requirements of the domestic population and add substantially to institutional operating and capital costs.

It has been estimated that between 30 % and 50 % of the jobs in an advanced economy do not require a university degree. This continuing expansion seems to be questionable.