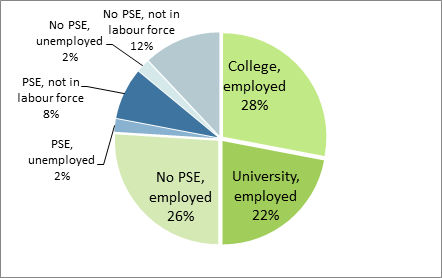

So, recently, a colleague sent me some data produced by CMEC on the subject of labour market outcomes by educational attainment, among 16-65 year-olds. Here’s the first one, showing outcomes for Canada.

Labour Market Status by Educational Attainment, 16-65 Year-Olds, Canada, 2012 (Source: The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, 2012)

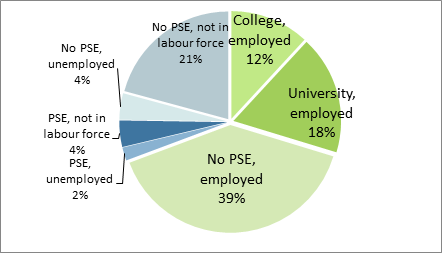

And here’s a similar one, showing the same thing for the OECD as a whole.

Labour Market Status by Educational Attainment, 16-65 Year-Olds, OECD, 2012 (Source: The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, 2012)

(Just so we’re clear, when talking about the OECD as a whole, “College” means PSE below bachelor’s degree [ISCED 4/5B for higher ed data nerds], “university” means PSE bachelor’s degree or higher [ISCED 5A/6], and “PSE” refers to the two combined. That’s not a perfect translation of what those qualifications mean in other OECD countries, but it’s close enough.)

If we compare Canada and the OECD, we notice two things right away. First, there are some pretty massive differences in education levels. Fully 60% of Canadians have some kind of credential, compared to an OECD-wide average of just 36%. Second, there is also a difference in employment levels: 75% in Canada versus 69% in the OECD.

An optimist (or at least a higher education lobbyist) would no doubt try to link these two factors, and say: Yay Canada! Our higher attainment rate causes higher labour force participation rates! And while that’s certainly one way to read the data, it’s not the only way.

Try looking at it like this: in both the OECD and Canada, exactly one-sixth of the PSE-educated population is either unemployed or not looking for work (6/36 in OECD, 10/60 in Canada). In Canada, 35% of people with no PSE are either unemployed or not looking for work; in the OECD, 39% are. Not a huge difference. A much more pessimistic reading of this data, therefore, is thus: to a large degree, Canada educates people to no real purpose. The fact that we have a higher percentage of the population educated hasn’t appreciably increased the probability (at least vis-à-vis other OECD countries) that those with higher education are employed.

There is, of course, a third reading of the data: that education levels and employment levels aren’t linked statically in any meaningful way. National labour markets develop in different ways over time, in response to varied economic conditions. Countries with varying education/skill compositions can have similar levels of employment (though not necessarily similar levels of national income); conversely, countries with identical sets of skills can have quite different levels of employment and output, depending on a host of other institutional and environmental factors. As a result, generalizing about economic outcomes based on educational ones is a bit of a mug’s game.

I’d kind of like the first option to be true. But overall, my money’s on number three.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thank you for this interesting data and your (quite reasonable) take on it. Without disagreeing with the likelihood of your third interpretation, I would urge 2 little bits of caution.

First, there’s some danger in making interpretations that group unemployed and out-of-labour-market populations in analysis. In some OECD countries, certain populations (e.g. women) may be less likely to ever intend on being in the labour market and may therefore not seek PSE. In those cases, the labour status is more like the independent variable and the education the dependent variable instead of the other way around.

Secondly, I fully agree with your ‘warning’ not to causally link educational attainment and employment, I argue that there is still a case to be made in many regions for linking educational attainment to employability. The difference being that employment is a collective rate and employability is a measure of an individual’s likelihood of gaining employment in whatever market and at whatever rate of employment exists in that market. Policy makers are rightly interested in questions of how promoting public education might affect employment rates. But individuals want to know if there is a Return on Investment for their efforts in PSE. A labour market, being a market, may not employ more people if more people have PSE, but it is more likely to employ the people who have an educational competitive advantage. I would hate for anyone to interpret your conclusion that Canada is educating people without achieving the purpose of higher employment rates as meaning an individual is not more likely to be employed if they have PSE in the Canadian market.

P.S. “no real purpose”….ouch! I always enjoy your tongue-in-cheek and direct commentary, but I also always want to remind readers that there are other purposes to PSE other than employment/employability.