Morning all. It’s been just over a year since the Laurentian University President and Board of Governors made the decision to declare insolvency. Largely because of the institution’s decision to maintain radio silence with its own community and with journalists it doesn’t feel it can handle, there are major aspects to this story where we still do not have a complete picture of what happened, either in the long term (how did Laurentian get into this pickle) or the short-term (what were the specific steps in 2020-21 that led to seeking CCAA protection and – crucially – were there any alternatives?). I spent a good part of the holidays going back through the public record to try to work out some of this stuff. What you’re going to read for the next four days are the fruits of that effort. Today’s effort looks at the story of Laurentian’s mid-decade construction spree, tomorrow’s will take us through the key events between the building spree and the arrival of COVID, Wednesday’s will look at the ten months leading up to the Insolvency announcement, and Thursday will look at what we can learn from all of this and what Laurentian’s way forward will be.

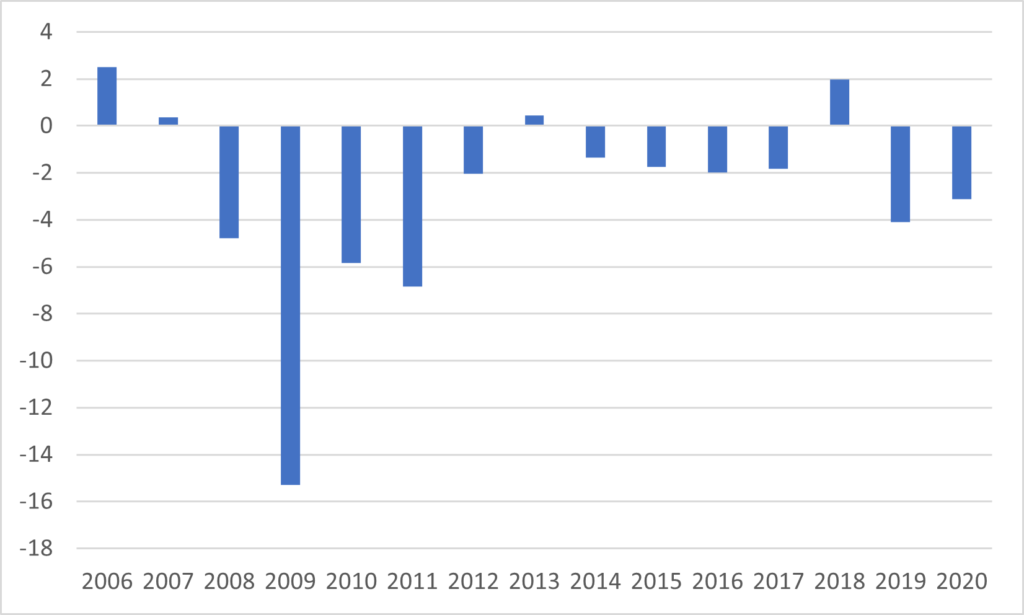

Laurentian long had trouble balancing its budgets. Figure 1 is the institution’s total revenue minus total expenditures for the past 15 years (the 08-09 figure is pretty eye-popping – something that happens when a generous new faculty agreement kicks in in the same year as a global financial crisis).

Figure 1: Laurentian University’s Revenue Minus Expenses, (in unadjusted millions of $s), Fiscal Years Ending 2006-2020, in millions.

You should take two things from Figure 1. First, and most obviously, sustainability was not Laurentian’s strong suit, and literally no one on campus should have been in any doubt that the institution was in serious trouble heading into COVID. But if you look more closely, you can also see why Laurentian might have thought it had turned the corner around 2012-3 and was in a position to dream a bit larger. And that’s exactly what leadership did:

- They gave its student residences a serious renovation: a good investment since demographic trends showed clearly the university was going to need to attract a growing number of students from outside the Sudbury area to survive. This cost $7.7 million and was completed in mid-2012.

- They built a new and quite glorious building in downtown Sudbury for its school of architecture. Cost: $42.6 million, later defrayed by $10 million through a donation from Ron and Cheryl McEwen.

- There was a $50 million program of renovation and building (250,000 sq. ft of the former and 20,000 sq feet of the ladder, where the latter was largely for a new student centre and the also glorious Indigenous Sharing and Learning Centre), simply known as “Campus Modernization.” Some of this cost was offset through donations and dedicated student fees.

- They built a massive (47,000 sq ft) new addition to the Engineering Building at a cost of $30.3 million.

- Pay attention to this one: they built a Cardiovascular/Metabolic lab which initially was supposed to cost $5 million (later rising to $6 million) more or less specifically to house the research unit of the university’s new VP Research, Rui Wang.

And remember, it did this at a time when the unrestricted operating deficit at the end of fiscal 2014 was $8.2 million – but, as Figure 1 shows, things appeared to be getting better.

One needs to get deep into the financials to understand what was going on, but there are two key points that became crucial in early 2021. The first is that not all of this construction was covered by long-term debt, and the second is that the long-term debt was all unsecured, because a) the banks assumed the university was implicitly guaranteed by the provincial government and b) what’s the point in having the option to re-possess part of an Engineering building (for example) when it would have almost no value to anyone other than the university itself?

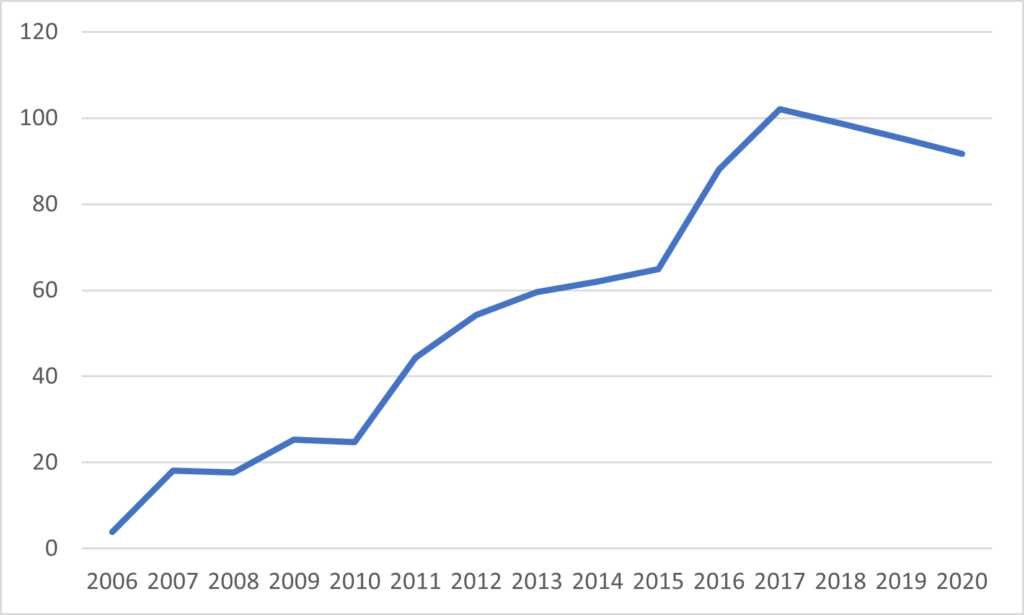

As Figure 2 shows, the long-term debt would eventually reach its peak in the 2016-17 fiscal year, at just shy of $102 million dollars. When people talk about Laurentian having gone on a construction binge, this is usually what is brought to mind. Laurentian was paying well over prime on these loans: different loans had different effective rates, but the blended rate on the whole debt was about 4.5%, well above prime. This may sound a foolish waste of money, but it’s a pattern seen across many Ontario universities; U of T’s blended rate on its $710 million or so of long-term unsecured debt is actually slightly higher, at 5.26%. The bet universities are making is that locking on these rates will save them money in the long run (the maturities on these loans are all 15-25 years in the future). In any case, actual annual payments on these debts were never more than $3.5 million, or, put another way, never more than 2% of university expenditures.

Figure 2: Laurentian’s Long-term debt (in unadjusted millions of $s), fiscal years ending 2006-2020

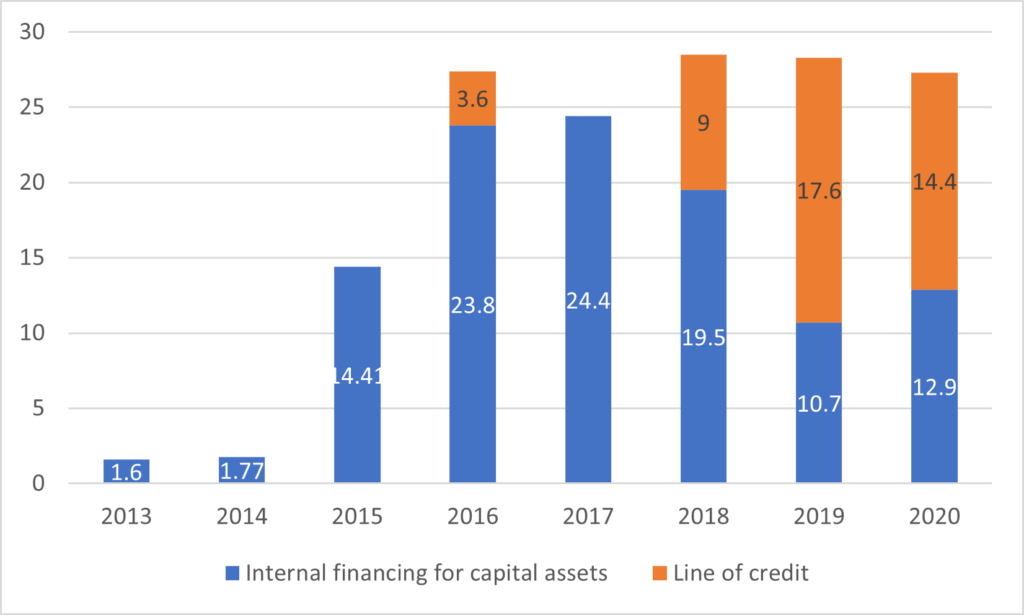

But the real action was in the stuff not covered by long-term debt. These were covered by “internal financing”. Apparently, the university had always done this in a small way, but never for more than $2 million in a year. In the years after 2015, this sum raced up to over $20 million. About a third of the Campus Modernization ($17 million) project was financed this way, as was the entirety of the Cardiovascular/Metabolic Lab ($6 million) and sundry amounts for other projects. Essentially, the university was lending to itself for these sums.

But from what funds?

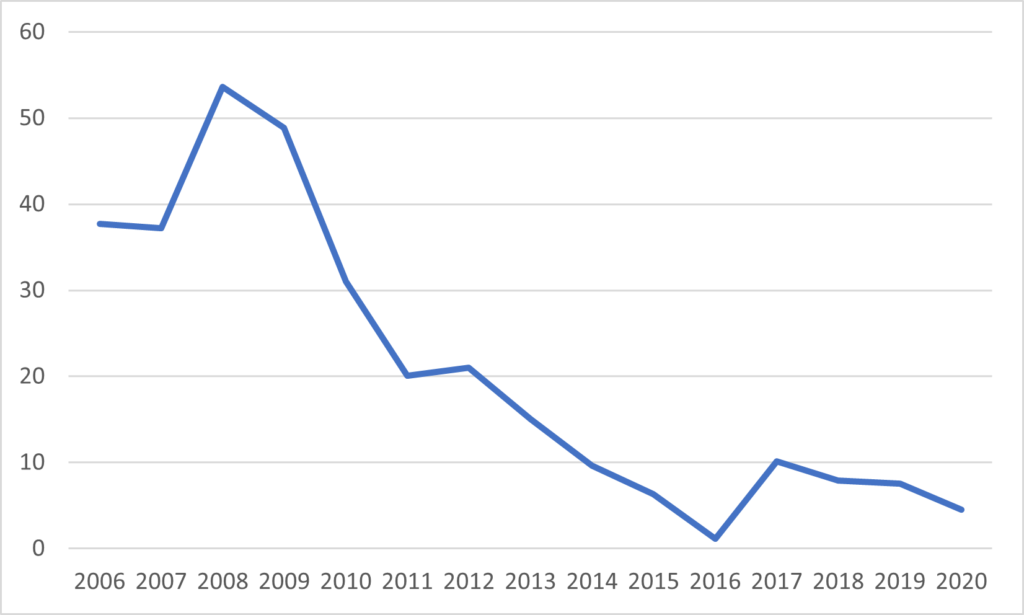

Internal net assets were negative because of years of deficits (almost $20 million by April 2020). And the answer is that the university seems to have been spending various parts of its piggy bank for things like pensions, future benefits liabilities, research grants, etc., and calling it a “loan”. You can see how bad things got just by looking at their cash/short-term investment position on April 30 each year. On average, for the last five fiscals for which there is data, cash was equal to about 3% of total expenditures. Adjusted for revenues, if you look at universities with under 10,000 students across Ontario, Laurentian was holding cash balances of about half to one-third of the Ontario norm.

Figure 3: Laurentian Cash and Short-term Investments (in unadjusted millions of $s), fiscal years ending 2006-2020

Eventually the cash crunch got too much. Laurentian began to look to the banks for lines of credit, and received two: one from Desjardins for $26 million, and another from the Royal Bank for $5 million. Basically, the institution was having trouble staying liquid through the entire year based on its own resources, particularly during the eight-month gap between students’ January and September tuition payments. So, it would draw on that line of credit in, say, February, and then pay it down each fall. Naturally, these sums showed up on each April 30 financial statements. But, weirdly, they would show up as “repayments” on internal findings (see note 12 in the 2019-20 Financial Statement). So to understand the real situation you have to portray both the internal financing and the lines of credit, as below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Laurentian Internal Financing Plus Outstanding Lines of Credit (in unadjusted millions of $s), fiscal years ending 2013-2020

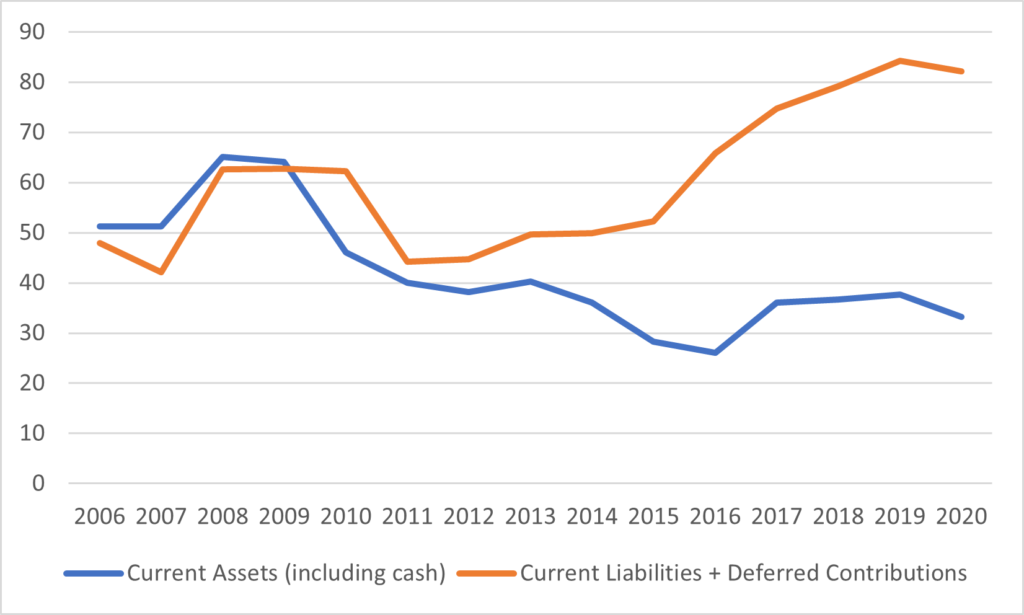

Here’s the takeaway from all of this: Laurentian was in trouble in the late oughts. By the early 10s, it had righted the ship somewhat and begun making large investments in new research facilities, student housing and overall renovations. It should have been clear to the Board and anyone else watching closely (this includes the union, which had an ex-officio non-voting seat on the Board) that the university was sailing very, very close to the wind. As Figure 5 shows, in 2013 the institutions’ current liabilities and deferred contributions combined were at least in touching distance of its current assets. But that position deteriorated rapidly over the next five years. From 2014 onwards, the institution was increasingly exposed financially, and while it made progress on its long-term debt, on the short-term liquidity front it was still vulnerable to external shocks.

Figure 5: Laurentian Key Financials, 2006-2020

Tomorrow, we will look at those shocks in detail.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

High risk financial situation was not met with appropriate finncial wisdom..

This is very good but omits two aspects 1. No declaration that he is a consultant to universities especially regarding the attracting of foreign students and that some of his reporting might have a self interested bias or conflict of interest 2. No acknowledgement of others’ analysis who earlier pointed out the mounting debt and deficit situation under the Giroux regime, indeed he mentions the dates but not the persons in the administration and on the board, aside from the deal with Wang. Even undergraduate essays are expected to provide information on other, differing or similar accounts. Readers might want to consult, among other, https://www.thesudburystar.com/opinion/columnists/unmaking-a-university-laurentians-insolvency

Hence, this remains a start and we have to see if the auditor General can pin down who is responsible for what when.

I look forward to the next instalments.

Dude, this is a corporate website. If you come here and read a piece and not realize that it is coming from a consultant, that’s on you not me.

Your form of address says much about your ethical approach

In my view, unethical is coming to a website that is openly a page for the consultant’s business, criticizing said individual for not declaring their potential bias as a consultant (which should frankly be obvious to anyone reading), then using their platform to promote your own piece on the matter in question.

Further, you previously cherry-picked a remark from a previous article on this website and accused Mr. Usher of defending the Laurentian administration when he later used that point to “call bullshit” on the administration’s claims. But he’s the unethical one, is he?

The tax payers of Sudbury also contributed $10M to build the school of architecture.

There are two other factors affecting the budget which you are neglecting. First the huge growth in the the administration over the past several years which has been partially addressed in the CCAA process. The second was the growth in thr faculty and staff who chose not to retire after 65 which strongly impacted the budget as these numbers grew. Both these factors are infecting other universities colleges and hospitals and needs to be addressed by the government.

I was President of Laurentian University from 1998 to 2001. At the time, we had a zero based budget, strongly enforced by my Board of Governors.

Tough and very unpopular decisions had to be made by me and my entire management team on a regular basis to keep the budget balanced and on track.

During my tenure, Mr. Ron Chrysler, was the VP of administration and the financial overseer. He was a very tough, an extremely knowledgeable and an outstanding ethical administrator for whom I had a lot of respect.

He managed the finances of Laurentian as though every cent was coming out of his own pocket. I listened to him and in most cases followed his sound advice. I had and have the upmost respect for this incredible man.

The University was very fortunate that this gentleman was in charge of its finances for so many years.

The dismal financial carnage and all its unfortunate consequences would never have happened under his guidance and his watch.

I would echo Dr. Watters comments about Ron Chrysler. I knew him when I worked at the Council of Ontario Universities in the 1980s and 1990s and always found him very knowledgeable and approachable. – James A. McAllister, Ph.D.

As rightly pointed out by a commentator on this thread, you should have declared your conflict of interest as someone who had served as an advisor to a previous President of Laurentian University (at least this is what I have heard). Hence, your take on/analyses of the university’s affairs are questionable, to say the least. Regardless, the whole truth will come out – just a matter of time.

A minor correction to D.. Goldsack’s comment above: I am a retired Ontario community college faculty member. I was appalled when I heard that Laurentian (and other universities’) faculty were receiving both pension and salary. This is blatantly unethical, and is ruled out in the college system under the terms of the pension plan. Perhaps some retired faculty assume short-term, part-time contracts to fill needed gaps in certain specialties, but one cannot be simultaneously a full-time employee and a full-time retiree (unless the universities have some special quantum features in their budgets).