Universities – and to a lesser extent colleges – are dependent for their livelihood on a steady supply of young people coming through their doors. For the past decade or so, most of the young Canadian population has been on a downswing, with some parts of the country seeing their youth populations drop by as much as 20%. The result has been a slight drop in total domestic enrolment nationally, and some significant drops locally. At many institutions, this fall in domestic numbers which has permitted the significant expansion in the number of international students: had numbers been higher, there would have been no spare capacity.

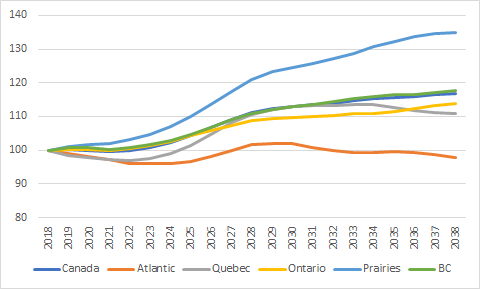

But we always anticipated that the drop in domestic numbers was going to reverse itself after a decade. And it’s now been nine years since the last peak. So, what does the future look like? Take a gander at Figure 1, which shows the anticipated change in the size of the 18-21 age-cohort out to 2038 (I tend to keep projections to 17 years, because at least everyone in the projection has been born).

Figure 1: Change in 18-21 Population by Region, Canada, 2018-2038, 2018 = 100

Nationally, the numbers will start to trend upwards after 2023, rise rapidly until about 2027 and then grow more moderately from 2027 to 2038. Overall: the growth from 2018 to 2038 will be about 17%, which is very respectable (if you’re having trouble spotting the “Canada” line on the graph, it’s because it’s obscured by BC, which mirrors the national trend almost completely for the entire 20-year period).

But while this national story holds for BC and Ontario, the rest of the country is a different picture. In the Prairies, we’re looking at significant growth rate through the entire two decades, culminating in a stunning 35% increase by 2039. In the Atlantic, numbers stay below 2018 levels until 2028, peek above them briefly for five years before slipping down again. And in between is Quebec, which mirrors the Atlantic for the next couple of years before spiking sharply and then falling off again in the latter half of the 2030s.

In other words, the picture really depends on what part of the country we’re talking about.

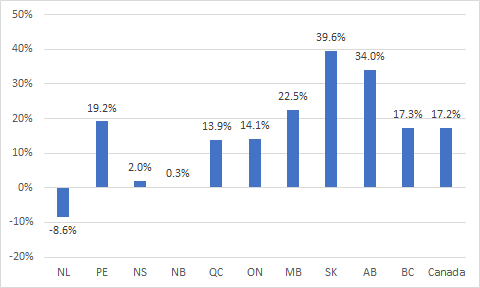

But even within regions the story isn’t always the same. Figure 2 illustrates the change from to the present to 2038, by province. Within the Atlantic, Prince Edward Island seems to be in decent shape; Newfoundland and Labrador is in serious trouble. In the Prairies, while all provinces are expecting serious growth, it is much more pronounced in Alberta and Saskatchewan (39%!!!) than it is in Manitoba.

Figure 2: Change in 18-21 Population by Province, Canada, 2021-2038.

There are some implications to all this.

In the Atlantic, the lesson is: there is no alternative to international students, barring massive increases in immigration. Provinces that are showing this level of demographic stagnation do not have money to spend on higher education: there simply is no scope for a public bail-out here. Based on this, I expect that by 2038 there will be a lot more institutions resembling Cape Breton University – that is, majority international students — particularly Memorial.

The Prairies – and especially Saskatchewan and Alberta – are in a different kind of situation. The kinds of numbers we are looking at here are huge: an extra 23,500 young people in Saskatchewan (basically another U of S) and 72,700 additional 18-21 year-olds in Alberta (basically, another U of A *and* another U of C). This implies a need to add capacity in a relatively steady fashion over the next two decades. But where does the money come from?

On the one hand, these provinces are going to be growing in population over the next couple of decades, and with it their capacity to finance educational institutions. But at the same time, the increasing number of potential domestic students means that institutions will have trouble accommodating extra international students. And in the short-run, because of provincial cut-backs, Alberta universities are banking heavily on being able to recruit international students. But what these numbers suggest is that absent some major public investment, institutions are probably going to have to start reducing their international exposure over the next two decades just to service local demand.

To a lesser extent this is a problem which is going to affect institutions in British Columbia and Ontario as well. The easy gains from international students have been won through a brief period in which domestic demand declined and there was some spare capacity that could be filled. All international students had to do was cover their own costs and everyone was a winner. But that time is over. Now international and domestic students are going to be more directly in competition with one another.

It’s going to get crunchy.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Great post. Wondering why universities, e.g. in the Prairies, shouldn’t pursue growth in domestic and international at the same time?

One thing worth noting is that 29% of kids under age 15 in Manitoba and 27% in Saskatchewan are Indigenous (compared to more like 15% of middle-aged adults). I don’t know how much of this growth in the number of youth in the Prairies is accounted for by Indigenous people, but it seems like it would be a significant contributor.

And university attendance/access among Indigenous people is horrendously low due to a multitude of issues and forms of discrimination.

*Could* these kids be going to university in a decade, if the Canadian government made very extensive and sustained efforts to increase equality of access to education? Yes.

Will they be? I’m less hopeful on that. Education gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians have been very slow to close – and at the university level, they’ve widened.

I would appreciate your thoughts on this.

Hi where did you get the data for sask and alberta?

If capacity is not increased in the Prairie provinces, could/would those students end up studying in the Atlantic provinces?

Reduce the length of full degrees from 4 to 3 years (or at least make it an option)? That used to be typical in the UK (well England and Wales). Could be achieved by increasing course density or length of semesters, especially in provinces where there’s significant pressure on numbers.

Signed, the product of a 3 year Hons degree (and 3 year PhD) in the late 70’s/early 80’s.

Two factors—from an Alberta perspective—to add to this.

While Alberta and Saskatchewan have the highest change in 18-21 Population by Province numbers they also have two of the lowest participation rates in college and university studies. Alberta is tied for lowest with 34% participation (from 18/19) and Saskatchewan is tied for 2nd / 3rd at 37%. Compare to BC at 43%, Ontario at 47% and Quebec at 50% (!).

Second, in Alberta, we are seeing a concentrated attack on higher education with unprecedented cuts to all institutions.

Even though Alberta may have a surplus of possible future students, they may not be as interested in attending and the institutions themselves may not be well placed to receive them. Additionally, with the unprecedented cuts and the concomitant knock-on effects, many students in Alberta may be looking to provinces that have invested in higher education.

Source: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2020027-eng.htm

This post has been eating away at my brain for several days for one reason in particular: The Statistics Canada projections appear starkly different than those from the UN Population Division. I did a quick comparison of the projected growth from StatCan M4 projection of 17-22 population to the UN’s “medium variant” for 2020 -2040 (the 5-year intervals are easier to deal with the UN data) and came up with 17% vs 6% growth, respectively. I haven’t had time to check that it’s an ‘apples-to-apples’ comparison, but my first take is that the datasets tell very different stories. That’s a concern for those of us who do comparative research and it’s going to keep me up nights until I understand why the two projections diverge so dramatically…