I spent Friday morning with a delegation of University Vice-Presidents at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s offices in Paris, discussing a variety of issues pertinent to Canadian higher education. As we ranged across a variety of topics, I realized I had fallen behind on my think-tank reading, because there were a few really important papers discussed that I had not read. I took some time over the weekend to read three of them and thought I would put on my knowledge-disseminator hat and give y’all the short précis.

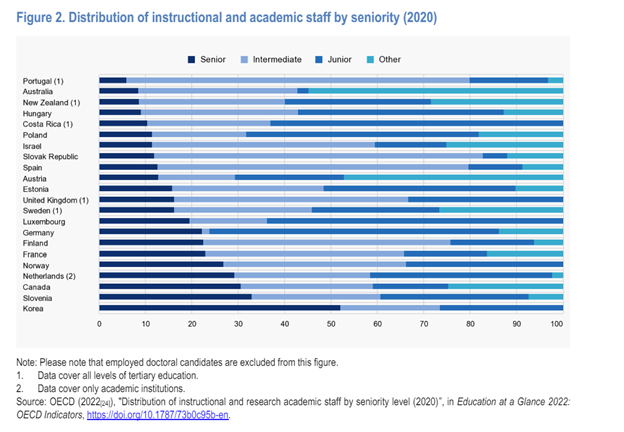

Maybe the most interesting was the one written on The State of Academic Careers in OECD Countries, which was in part funded from the European Union, which is starting to come under pressure from the higher education sector to find ways to harmonize academic careers in order to ensure/increase academic staff mobility from one country to another (an idea which is unfortunately pretty much entirely alien to the Canadian university system). It focuses on eight aspects of academic careers, some of which are dealt with in more accuracy and detail than others. But where it does have comparative data – which it does in spades around contract types – it’s pretty awesome. Below is cross-national data on what proportion of academic staff are at different levels of seniority. Canada stands out in relative terms as having very high levels of senior faculty otherwise known as full professors (believe me, if our pyramid looked like Israel’s or New Zealand’s, our institutions would be way more financially stable).

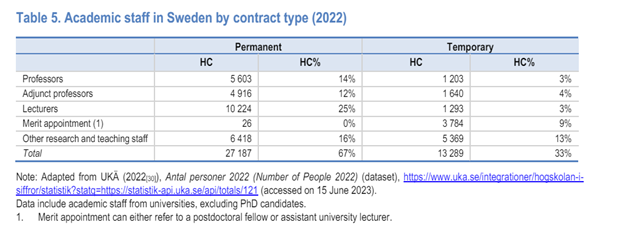

The report spends a lot of time on precarity in employment in academia particularly among early-career academics, and concludes (as I did last Wednesday) that it is a worldwide phenomenon, more or less regardless of the kind of funding or managerial systems in place. Occasionally, the piece provides some nice deep dives into national data series. Who would have thought that in hyper- egalitarian Sweden with its publicly funded universities, nearly half of all teaching academics (excluding doctoral students), roughly half would be outside the ranks of permanent, ranked academics?

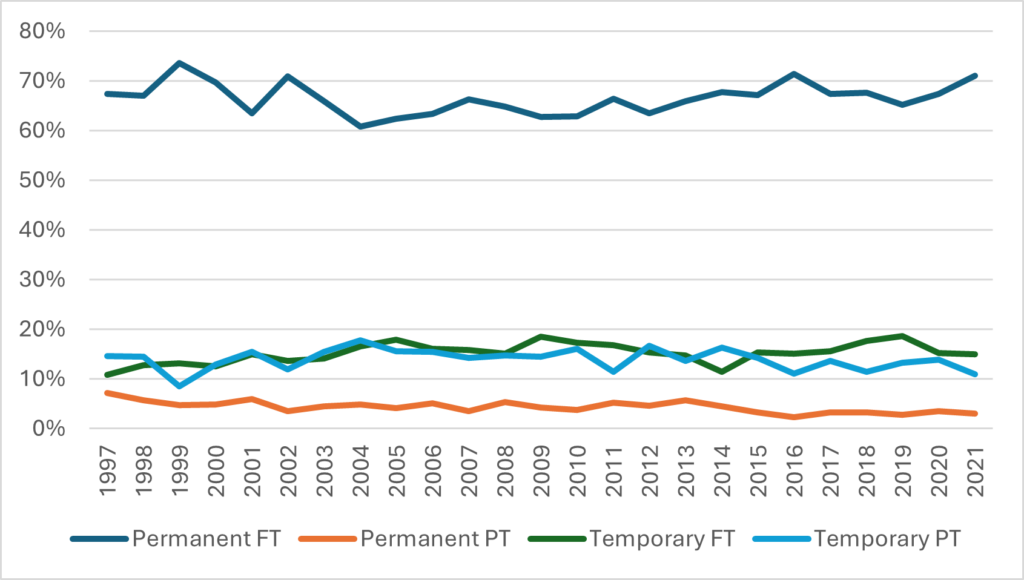

In fact, I would argue that the Swedish data, although calculated and portrayed differently, doesn’t look that much different from the data Canada, as this graph from The State of Post-Secondary Education in Canada, based on Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey data shows).

Figure 1: Distribution of Jobs among Labour Force Survey Respondents Indicating their Primary Occupation is Teaching in a University, by Intensity and Security, Canada, 1997 to 2021

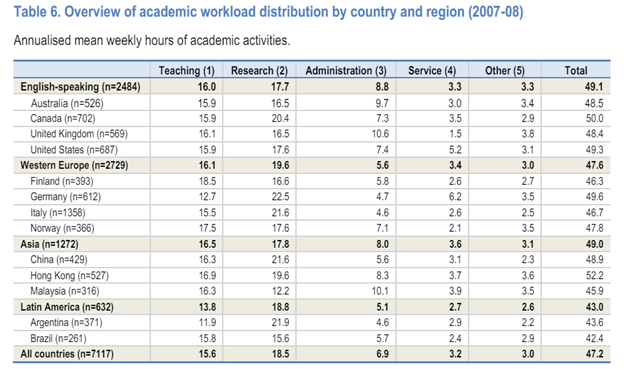

Another interesting aspect of this publications is the attention paid to academic workloads. Now, you can take these with a grain of salt if you want—all of them are based on time self-reports, which I suspect inflates the numbers a bit. But overall, I think the table below is a pretty persuasive demonstration of the fact that—again, regardless of funding levels or managerial regimes—both total faculty workloads (equivalent to a 6-day week) and the division of academic work between various tasks is actually pretty close to universal.

This work is important background to a discussion on a revision of academic workloads and career reward models, and I think this piece is very helpful in providing some interesting and useful new models that are worth watching in the years to come (in particular the new recognition and rewards model at the University of Utrecht known as TRIPLE, and the use of external panels to judge teaching merit in Sweden). There is also some interesting cross-national discussion about requirements for teaching credentials as well as research credentials in order to be a university professor (it still amazes me that no political party in Canada has never caught on to this one a potential vote-winner among students at election time).

The second publication I interesting was is called Doing Green Thingsby Stefanos Tyros, Dan Andrews and Alain De Serres, which uses cross-national data to look at not just which kinds of occupations are likely to be most affected by the green transition, but also which occupations are likeliest to be able to make such a transition. To quote the executive summary: Significant cross-country differences emerge in the underlying supply of green skill and the potential of economies to reallocate brown job workers to green jobs within their broad occupation categories. In a majority of detailed brown occupations, workers have in principle the necessary skills to transition to green jobs, with the exception of those in production occupations, who may require more extensive re-skilling. In contrast, workers from most highly automatable occupations are generally not found to have the sufficient skills to transition to green jobs, suggesting more limited scope for the net-zero transition to reinstate labour displaced by automation.

Do read it. There is a lot of fairly interesting data, of the kind of the kind we should be getting more often on more topics. Unfortunately, Canada is omitted because – surprise! No data! (though I don’t quite understand why: it seems to me that most of the relevant data or something quite close to it should be available). If I have a complaint with this one, it is that some of its analysis assumes away problems in geography. Sure, so-called “brown” (i.e. dirty) industry workers could transition relatively easily into green industries, but it’s not at all clear that in fact the jobs in one set of industries will be spatially located anywhere near those in the other, which makes “transitioning” from one to the other significantly more challenging. And to the extent that skills are transferable, it would be good for someone to pick up on this work and create something similar for other industries in transition.

The third and final piece to which I wanted to draw attention is called The Geography of Higher Education in Quebec, which was written by the OECD’s EECOLE unit which looks at the nexus of Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Higher Education (the keeners among you may remember my interview with EECOLE’s Raffaele Trapasso last fall). Nothing about the paper is especially groundbreaking in methodological terms: it is however a very thorough exposition of how universities in a particular jurisdiction contribute to their economies through technology and skills transfer, a mapping of some of the most important examples of university-business co-operation, and an overview of some interesting new policy initiatives (in particular the multi-dimensional “Zones d’Innovations” in Sherbrooke and Bromont). Add to that some judicious recommendations to build on the systems’ successes (and, the OECD seems generally less skeptical about Canada’s performance in innovation than most Canadian experts do) based on best international experience, and you have a policy document which is genuinely really useful.

Anyways, while these are all excellent papers that are worth your time, collectively, they also pose an important question: why does no Canadian government seem capable of putting out documents of this quality on topics like skills, higher education policy or innovation? It’s not like we’re incapable of doing it. We just…don’t.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Here is an interesting recent paper on academics time use. Seems like there is more variation across schools and profs than across countries.

https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/24-036_347e091f-838b-4ecc-b1a3-d793ea737188.pdf