Morning all. It’s the Wednesday after Labour Day and that means, as usual, that it’s release day for The State of Post-Secondary Education in Canada, by Janet Balfour and yours truly (with a big assist from Jiwoo Jeon). You can download it in all its glory here.

In many recent years, I have used this document to talk about international students and the increasing role they play in Canadian post-secondary finance, but I figure you guys have probably heard that story one too many times for it to interesting again this year. So for a change I wanted to look specifically at Canadian post-secondary education without international students. And the picture…well, it’s not great.

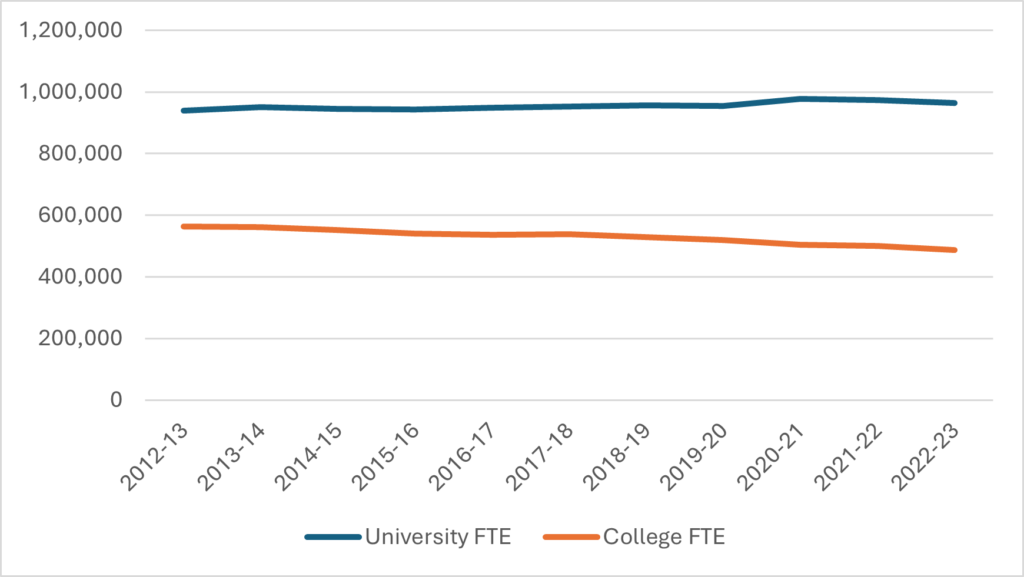

Let us start by looking at full-time equivalent domestic enrolments in Canadian universities and colleges over the past decade. Overall, enrolment is down by 3.5%, but the numbers at colleges and universities tell different stories. Domestic enrolments are up 2.6% at universities, but they are down by 13.6% at colleges, where enrolments now sit at their lowest level since 2003. The decline in college enrolment is most pronounced in non-Polytechnic institutions outside Quebec, which is to say institutions that are primarily located outside of large cities.

Figure 1 – Domestic Enrolment, Full-Time Equivalent Basis, 2012-13 to 2022-23

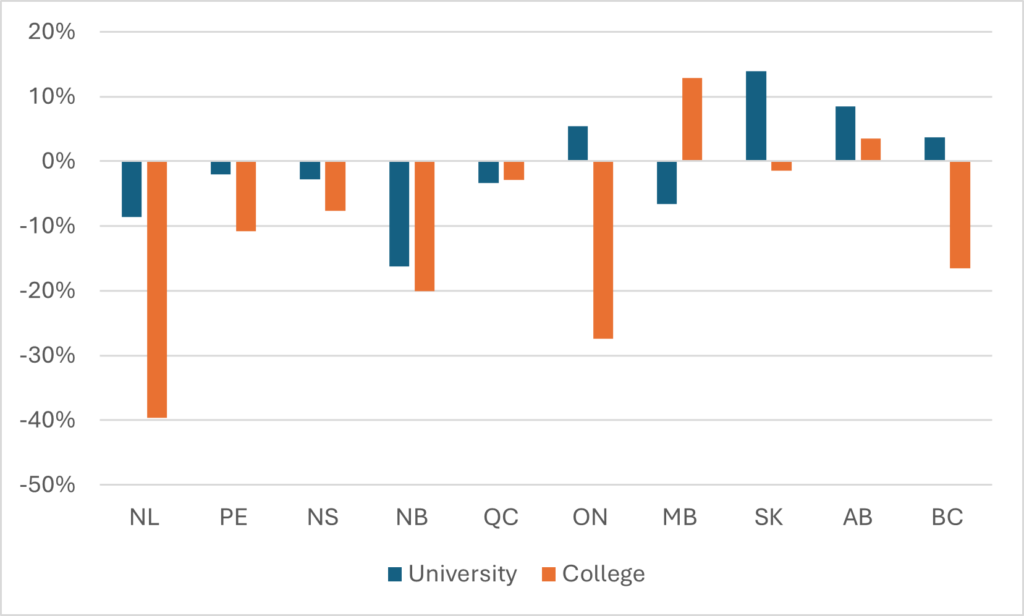

Naturally, this pattern differs by province. East of the Ottawa River what we see is a pattern of universal decline in both the university and college sector. New Brunswick has seen double-digit declines in domestic enrolment in both universities (-16%) and colleges (-20%). College of the North Atlantic in Newfoundland has undergone a remarkable drop of 40% in domestic students. But west of the Ottawa River, there are bright spots. Domestic enrolments at Ontario universities have risen by 5% since 2012, but college enrolments have crashed by 27%. Similarly, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia have seen rises in one sector and declines in another. Alberta is the only province in the country where enrolments are up in both sectors.

Figure 2 – Change in Domestic Enrolment by Province and Sector 2012-13 to 2022-23

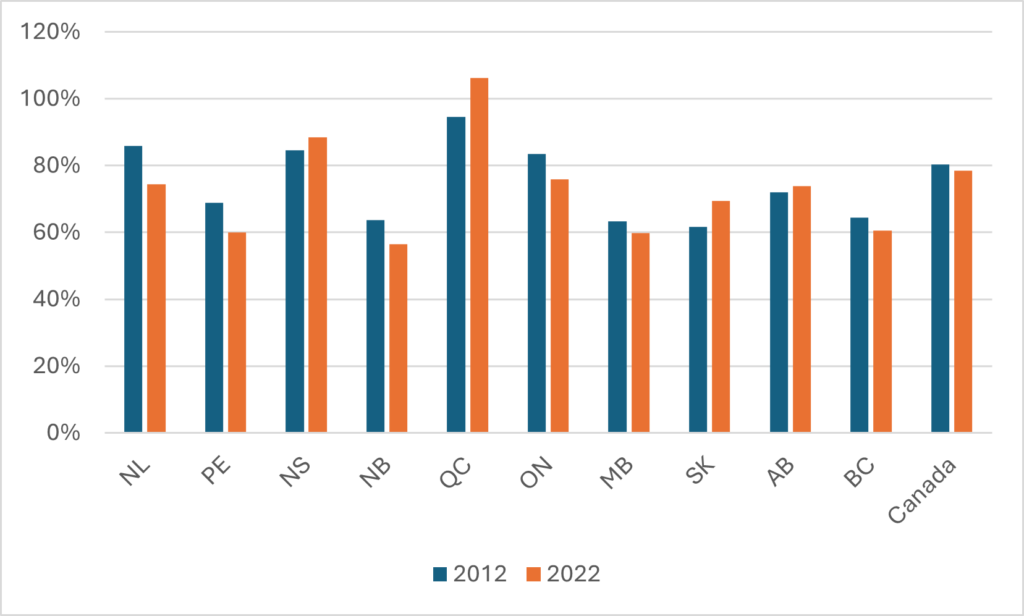

Nationally, a portion of this enrolment weakness can be laid at the feet of a declining youth population: the number of Canadians aged 18-21 declined by about 1.2% between 2012 and 2022. But that still leaves a substantial chunk of declining students unaccounted for. Figure 3 shows estimated domestic gross participation rates[1] by province from 2012 and 2022. In six of ten provinces, the participation rate fell. In Newfoundland, the decline was an extraordinary 12%. But in others, notably Saskatchewan and Quebec, it rose substantially (in Quebec’s case, it was a matter of enrolments staying stable even as the relevant age cohort fell in size by close to 15%).

Figure 3 – Gross participation rates by province, 2012-13 vs 2022-23

It is difficult to know what to make of this data because the patterns are not consistent across the country. In theory, with youth population numbers set to increase substantially over the period 2022-2032, we could see very large increases in enrolments: on the order of 15% east of the Ottawa River, and ranging from 15% in Ontario to around 35% in Alberta on the other side of it.

But is the system actually prepared for this wave of new domestic students?

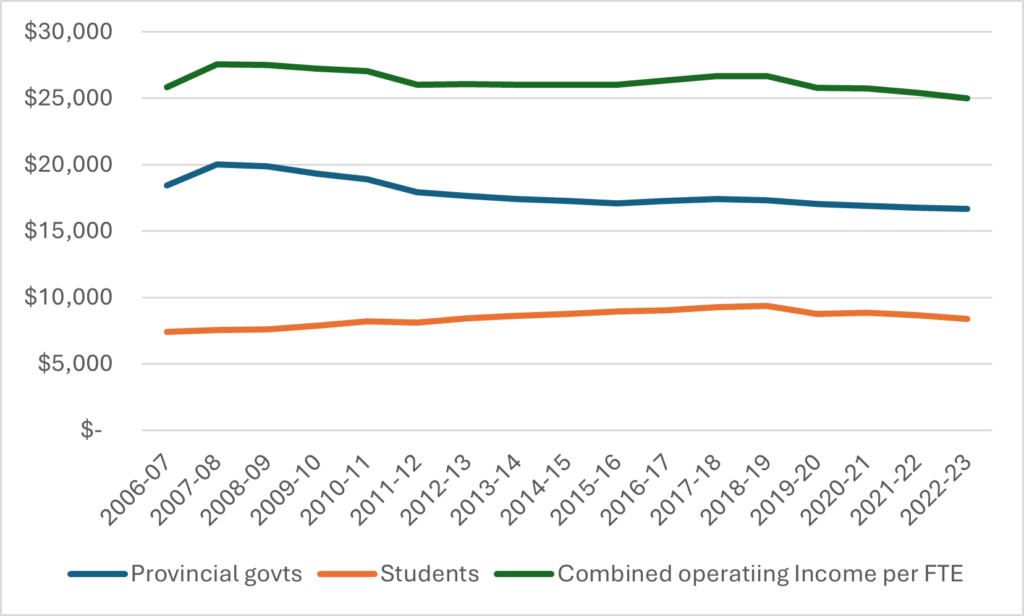

Figure 4 shows university operating income per domestic FTE student from 2006 to the present day. Provincial government support for universities peaked in 2007 and has since fallen by about 15%. For several years, this decline was offset by rising tuition fees; however, for the past few years, tuition fees have been falling in real terms. As a result, total domestic operating income per domestic student is down 9% from its all-time high in 2007 and 6% from when national tuition levels were at their height in 2019. It has fallen the most in Alberta, Ontario and Newfoundland, but has actually risen somewhat in British Columbia and Quebec.

Figure 4 –Operating Income per FTE Student by Source, Canadian Universities, 2006-07 to 2022-23, in constant $2022.

The last time a big wave of new students hit higher education during a period of underfunding was in the late 1990s, when the front wave of the so-called “baby-boom echo” graduated from secondary school. Then, universities and colleges were given large increases in public funding and were also allowed to raise tuition in order to get themselves out of a hole and accommodate larger student intakes. There is no sign whatsoever that something similar is about to unfold this time out. The allure of foreign student dollars over the past decade or so is, in this context, pretty clear. And while some have speculated about whether international students are taking spaces away from domestic students, it is worth asking the question: will universities be able to handle the influx of domestic students without the income that international students provided? If not, and institutions close their doors to new students because they can no longer sensibly accommodate growth in student numbers, as many effectively did in the mid-1990s, it seems likely that access to education will become a much more salient political issue in the coming years than it has been in quite some time.

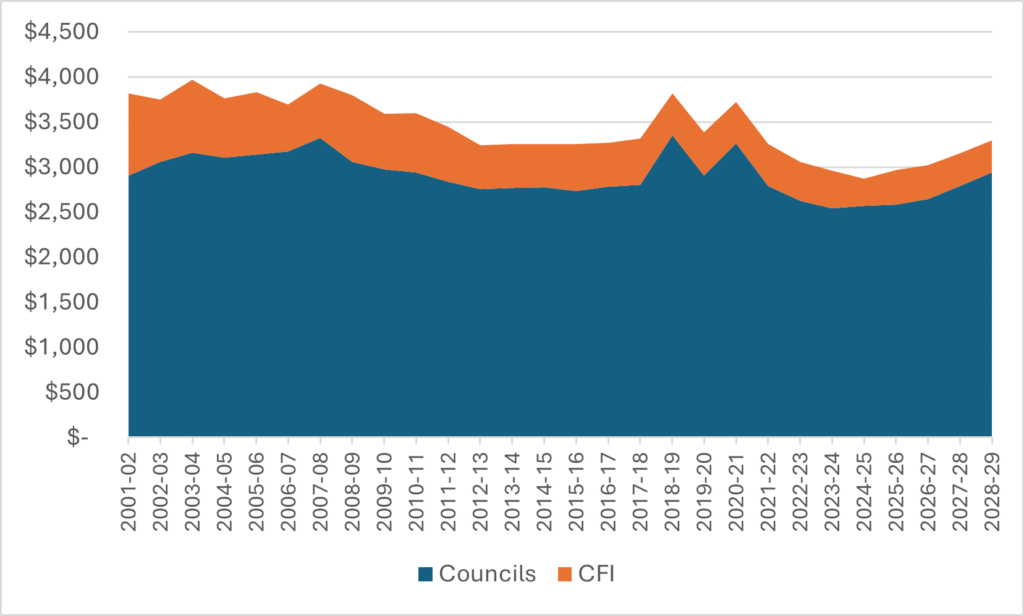

Enrolments trends are far from the active dynamic in post-secondary in Canada. It would be inappropriate, for instance, to provide a summary of the current state of Canadian post-secondary education without looking at research. Figure 5, below, puts total federal expenditures on the tri-councils and the Canada Foundation for Innovation into long-term perspective.

Figure 5 – Historical and Projected Institutional Income from Tri-Councils and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, 2001-2 to 2028-9, in millions of constant $2023

Despite a widespread perception that the Trudeau government is friendlier to research than its Conservative predecessor, the plain fact is that it has allowed inflation to erode science budgets. New investments from a much-vaunted five-year investment program announced in 2018 were entirely eaten away in real terms within of the new investments coming to an end. A major set of new research investments were announced in Budget 2024, but 88% of the new investments are slated to come after the next federal election. If they Liberals win, these commitments are safe; but if a tax-cutting Conservative government comes to power there is no guarantee it will view these commitments as binding. Meanwhile, total research funding for 2024-25 is actually down somewhat. It’s now at its lowest level in over 25 years in inflation-adjusted dollars because of a major clawback of unused (carried-forward) funds at the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

In summary, then, when we look up from the issue of international students and the income they do or do not bring to the Canadian post-secondary sector, the picture is not encouraging. It is one of stagnant or declining domestic enrolments, along with stagnant or declining per-student funding. A demographic bulge may be about to bring a new wave of students to Canadian institutions, but there is little sign that governments are interested in either providing the additional support or allowing institutions to meet the extra costs associated with this: neither funding rises nor rises in domestic tuition levels seem to be on the horizon. This will leave institutions a choice between denying access to part of this new youth cohort or teaching them with significantly fewer resources per student. And all the while, Canada’s scientific research capacity is eroding because the federal government seems unable or unwilling even to keep investments rising with inflation.

It is not condition red, exactly. But it is flashing a rather deep shade of yellow.

[1] Technically, Full-time equivalent domestic enrolment in both colleges and universities divided by total population aged 18-21.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Demographics vary widely across the country. University age population drop this past decade was supposed to be much more significant in Atlantic Canada

I have downloaded the report. Glad to see it on my RSS feed. I may be the only person in the world still using an RSS reader, but I like it!

Thanks for this. Always good to see the apocalypic state of the sector with some numbers attached.

The 27% drop in domestic enrolment in Colleges in Ontario is striking. Curious to know if this an even drop across the 24 colleges? Alternatively, is there’s a relationship between the Colleges that rapidly transformed towards the international market (eg, Conestoga, Fanshawe, Niagara, Seneca) and a resultant decline in domestic enrolments as they took a reputational hit, especially in the past few years? Or does the expansion and huge budget surpluses translate to more marketing and newer facilities that attract more domestic students while the Colleges that were more tentative with international visas (Fleming, Confederation, Mohawk) have fewer funds so suffer the greater drop in domestic enrolment?

So many questions…