Our annual publication, The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada, is out today. You can read it here. Consider it your free annual almanac of everything PSE-related in Canada. If you have any suggestions for improvement in future years, please let me know.

This is an odd year to be writing almanac-like documents. Normally, you can look forward to future events by relying on data that are a couple of years old. Partly, it’s from necessity, thanks to Canada’s lackadaisical attitude to producing decent data. But also it is because in most years, annual shifts don’t matter much. Most trends in PSE are long-term and the fact that you have a bit of a data lacuna doesn’t substantively impact future forecasting.

Not this year. 2020 is one big hairy discontinuity and predictions made off old data won’t cut it.

That’s why the main innovation in this year’s edition – apart from a new chapter looking at graduate outcomes – is a new approach to data collection. For financial data, instead of waiting for Statscan to do its thing, I have consulted every single institution’s financial statements directly, giving us a largely complete picture up to the end of the 2018-19 fiscal. Similarly, for universities, I have used institutional sources to get student data up to 2019-20. This was a long and – trust me – painful process, but we now have some relatively up-to-date data to help us understand if not how the COVID crisis will resolve itself then at least which institutions are most at risk from an international student collapse.

We all know the basics of the story: in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Canadian governments stopped increasing their spending on postsecondary education, but universities and colleges didn’t stop wanting more money. Instead of reducing the rate of spending growth, many of them chose to ramp up the recruitment of high fee-paying international students. From 2007-08 to 2018-19, international student fees grew from $1.5 billion to $6.9 billion (both figures in 2019 dollars), and from 4% to 13% of total system income (colleges and universities combined).

In short order, the system became addicted to international student money. Not equally by any means: Atlantic universities and Ontario colleges engaged in this game more heavily than others. But for those institutions that partook in the feast, the results were phenomenal. Since 2012-13, funds from international students have covered slightly more than 100% of the collective increase in operating budgets. Every faculty member at every institution who saw their pay rise in the last five years did so because of international students. All the new student services and IT personnel who were hired over the last five years have jobs thanks to international students.

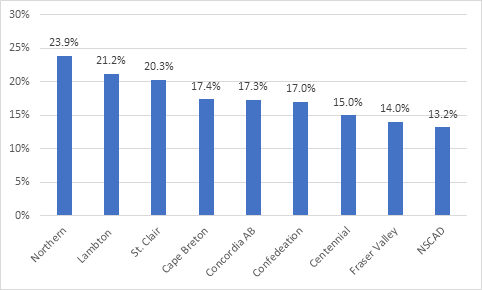

Surpluses have piled up at institutions across the country. Some institutions saw their net margins – that is, the surplus of regular (non-donation) income over expenditures – rise to well over ten percent. Figure 1 shows the institutions with the largest net surpluses. Unsurprisingly, most of the institutions on the list either have student bodies composed of over 25% or have recently seen increases of 50%+ in their international student numbers.

Figure 1. Top Canadian Postsecondary Institutions by Operating Margins, 2018-19

(A note here: because Figure 1 is in percentage terms, it misses some institutions whose surpluses are massive in absolute but not relative terms. For instance, Western’s margin in 2018-19 was $113 million, UBC’s was $136 million, York’s was $156 million, and Toronto’s was an eye-popping $403 million, or about $10 million more than the entire budget of Wilfrid Laurier University. Yes, really.)

The point here is that yes, many institutions are highly reliant on international students. But many institutions were also socking away money in the months before COVID, which means they might be well-placed to survive a temporary financial hit. The institutions that are going to be hit hardest by COVID aren’t simply the ones that have a lot of international students – they are the ones with a lot of international students and weaker financial positions.

So, which institutions are most vulnerable? Well, it’s difficult to say on the college side because so few colleges make data on international student enrollments available. Only in Ontario do we have decent data (and you can see their data in the introduction of today’s publication – tl;dr they were mostly saving money away at an astounding rate but Cambrian. Canadore and Seneca might be int the most danger). But on the university side, it’s better. Apart from the UQ system and a handful of smaller institutions in Ontario and BC, we have pretty complete international student data up to 2019-20. And what that allows us to do is to take a look at institutions according to both their financial position and their international student numbers, which I do below in figure 2.

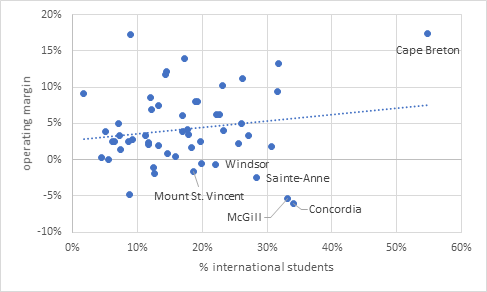

Figure 2: Operating Margin vs. International Student Enrolment, Canadian Universities, 2018-19/2019-20

The way to read Figure 2 is as follows: an institution in the top left corner is both financially healthy and has low exposure to the international student market. Institutions in the bottom right-hand corner are financially in trouble and have high exposure to the international student market. As the trendline shows, institutions which have more exposure to international students tend to be better-off financially because, hey, money! Take Cape Breton, for instance: massively exposed to the international student market but also the biggest operating surplus in the country. On the other hand, there are a lot of institutions which have high international student numbers and yet are still running deficits: in particular, Concordia, McGill, Sainte-Anne and Mount St. Vincent. These are probably the most theoretically vulnerable institutions right now.

(Note to McGill folks. Yes, I know you theoretically ran a balanced budget in 2018-19. But it was dependent on donations, which are excluded from the margins for all institutions because it’s not clear what proportion of these donations are actually accessible for operations in the financial year and how much is going to endowments).

Now, theoretically vulnerable is one thing – actually vulnerable depends on international student behaviour: what has actually happened to new international enrolments. Have they been convinced by our efforts to make for a good online semester (or two)? Institutions, for the most part, aren’t talking about this publicly, so we don’t know yet. My bet is international enrolments are down, but not as much as initially feared. But on the other hand, the drops will be felt unequally: high-prestige institutions like McGill will probably be ok, but I suspect things will be tougher for institutions like Mount St. Vincent.

All of which is to say: international students have, for many years, been the tidal force keeping the system afloat in the absence either of more government spending or of concerted institutional cost-control. But as Warren Buffet once famously said, “only when the tide goes out do you discover who has been swimming naked.” For Canadian higher education, COVID is the ebb tide. The system will no doubt survive, but it’s not yet guaranteed that all individual institutions will do so in their current form.

Happy reading.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

In figure 2 there are some outlier institutions in the top left that have high operating margin but low (relative) exposure to international students. I’d be interested to know who those were and your thoughts on them.

Two thoughts about the report on the state of college and university finance.

The smart question about how “balanced” McGill’s budget really was and the difference between expendable gifts and endowed gifts can be taken step further. If the endowed gifts were restricted to purposes specified by donors, they may not serve to balance an operating budget. Bond rating agencies now take this into account and usually do not regard restricted gifts as collateral against risk.

Maybe some colleges and universities were deliberately, as you say, “socking away money” in anticipation of the impact of COVID-19 international enrolment. It may, however, be more coincidental than strategic, and as closely tied to a very recent event like the pandemic as it appears. In most cases, international students attract no public funding, and their fees are in effect unregulated market prices. Institutional fiscal stability over the first two decades of the 21st century was due, as HESA to its credit has shown, almost entirely to a 100 per cent increase in enrolment of international students. However, total income and expenditure per student over approximately the same period was virtually flat. There is an explanation for what otherwise might be seen as a contradictory conundrum. During most of the last decade demographic domestic demand for access declined, in some provinces by as much as 17 per cent. For many colleges and universities, this meant that international students were filling already funded under-subscribed places. Marginal costs did not rise, hence the surpluses available for “socking away.” This may have been as much good fortune as a long-term strategy. As domestic demographic demand for access begins to rise, as is projected between 2024 and 2026, even if international enrolment holds-up, the marginal revenue/marginal cost advantage will diminish. In that case, reserves can finance bridges but not solve structural shortfalls.