Good morning. Today marks the launch of the fifth edition of The State of Post-Secondary Education in Canada (SPEC). You can download it here. It’s a bit different from previous editions: it includes a new section on research in Canada, as well as a new Appendix containing a set of information-sheets for each province (patterned on the “nutshell” series which y’all seemed to have enjoyed). And I am sure it also includes a whole new batch of mistakes, too, which I look forward to hearing about as folks spot them, and for which I obviously take full responsibility.

We’d like to thank the sponsors for this year’s edition for helping to keep this a free publication: ApplyProof, World Education Services (WES), Studiosity, and Pearson.

For the most part, there were no surprises in this year’s data; this is higher education, and nothing moves all that quickly. The precise extent to which Ontario colleges have pivoted to serving the international market raised an eyebrow (see Chapter 1), perhaps, as did Memorial University’s intriguing research profile (Chapter 7). But one thing did stand out, and it’s what I want to talk about today: recent changes in the provision of student aid, and specifically the massive run-up in student grants which has been occurring.

Most people know part of this story: that the Wynne government in Ontario combined a number of loan remission and tax credit programs into one large up-front grant program which temporarily jacked up the availability of grants until the Ford government reversed many of the reforms. From this, people conclude that Canada is back at the status quo ante.

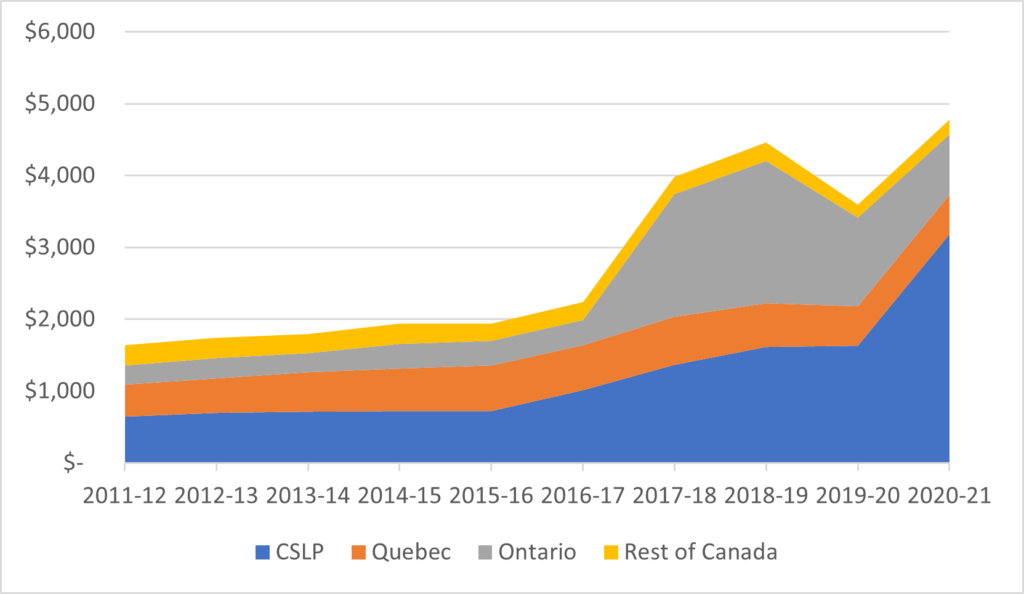

But this is not true. For one thing, Ontario did not reverse the policy entirely. And second, caught up in the all the commotion of COVID in early, the Trudeau government doubled the size of the maximum Canada Student Grant. This did not increase the number of students receiving grants, but it did significantly increase disbursements; according to the Canada Student Financial Assistance Program’s (CSFAP) Annual Report, the rise in annual grant spending due to this change was on the order of $1.5 billion. And what this means in turn is that in 2021, government grants alone (that is, excluding institutional financial assistance) constitute $4.8 billion, double the amount allocated in 2016-17 and nearly triple what it was in 2011-12.

Figure 1: Student Grants by Source, 2011-12 to 2020-21, in millions of constant $2020

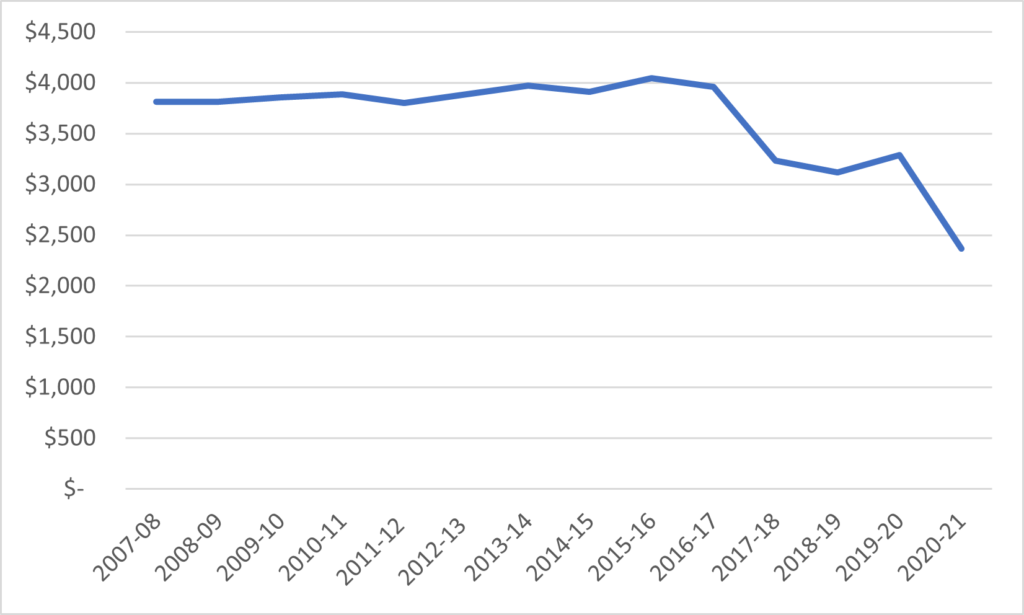

One way to show the effect of all this money is to look at what has happened to average “net” domestic tuition fees where “net” is equal to total fees minus total grants and divided by the number of full-time equivalent students. This is done below in figure 2. Domestic fee income minus grants (which here includes loan remission programs as they are simply delayed grants) per FTE student was pretty consistent from 2007 to 2016; since then, “net” fees have fallen by over 40%.

Figure 2: Net Tuition (Fee Income Minus Grants) per FTE Post-Secondary Student, Canada, 2007-08 to 2020-21, in constant $2020

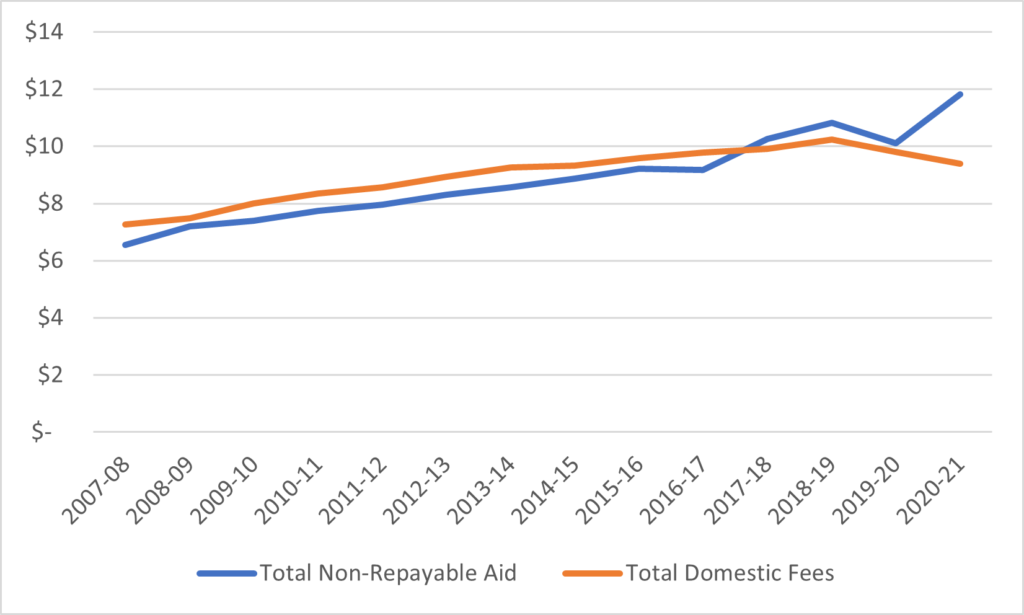

One could also justifiably take a wider view of “net” tuition and include not just government grants and remissions, but other forms of assistance as well, such as institutional grants/scholarships, tax credits and Canada Education Savings Grants. The total amount of all these types of assistance (but still excluding things like provincial or federal merit scholarships, the Post-Secondary Student Support Program which transfers money to First Nations to support their students, etc), is currently between $11 and $12 billion. Meanwhile, institutions’ take of domestic tuition fees has been falling, both because of decreasing rates and a decline in the number of domestic students. It has long been the case that Canada has had something like net-zero tuition in the sense that non-repayable assistance was roughly equal to total domestic tuition. Now, however, we appear to be in a net-negative tuition situation, where total aid exceeds total tuition taken in. This does not mean that every student receives more aid than they pay in tuition, but it does mean that a great number of students receive more in payments than they spend on tuition.

Figure 3: Total Non-Repayable Aid vs. Estimate Net Total Domestic Tuition Fees, 2007-08 to 2020-21, in billions of $2020.

Obviously, the key takeaway here is that Canadian policymakers – particularly at the federal level – have been paying keen attention to affordability over the years and, thanks mainly to the COVID crisis, have succeeded in addressing issues of affordability (even if this has not entirely sunk into the public consciousness). This is to the good. But at the same time higher education has another, perhaps more pressing issue, namely that government funding of institutions has not increased in real terms in nearly fifteen years, with the result that over the past ten years, 100% of net new income has been accounted for by international student fees.

The desire to fund students rather than institutions is easy to understand: delivering money to individuals makes for better retail politics than writing cheques to institutions or – God Forbid – provincial governments. But cheap education is not necessarily good education: institutions need to be nourished just as students do. If it were possible for some of this funding to flow through to institutions through higher (domestic) tuition fees, that would be one thing: but retail politics have taken over the tuition fee debate as well. The result is that despite this quite significant increase in public investment in higher education, institutions are only able to meet rising costs by going abroad for new students.

Now, it is certainly true that not all the push to attract international students can be laid at the feet of government restraint. In Ontario’s college sector for instance – by far the nation’s most egregious case with over a third of students and nearly half of all revenue now coming from abroad – the ratio of new tuition dollars to “lost” public dollars is about eight to one. Institutions are doing what institutions do when left to themselves: spending all the money they raise and raising as much money as they can. But this is perhaps precisely the problem: Canadian governments do in fact let institutions more or less get on with raising money without any interference. And so, the combination of limited local funding and seemingly limitless international funding is leading to what might best be termed sporadic internationalization of campuses, with very little thought or planning (particularly where student housing is concerned), and which is increasing leading to negative externalities in the communities where those students are located.

Other futures are possible for Canadian universities and colleges; ones which involve thoughtful system-wide planning, co-ordination between institutions and various levels of government, and above all more attention to local communities. But all these futures require governments to ease off on the exclusive focus on students and affordability and recommit to investing in institutions. Quickly.

In any event, happy reading.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post