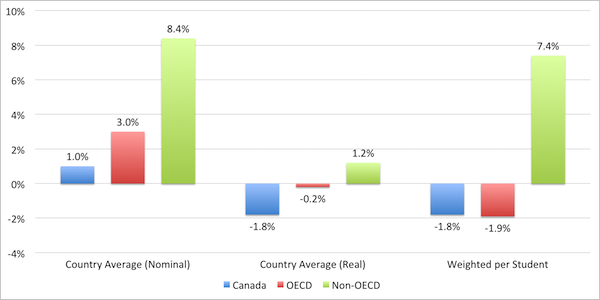

Sit down before you look at this graph, which shows new investment in higher education in 2011. The data comes from our annual survey of 40 countries around the world which make up over 90% of all enrolments and scientific production.

Change in Public Expenditures on Higher Education, 2011

The basic story here is this: in the OECD, we’ve finally hit what I call “Peak Higher Education”; the point beyond which we can no longer expect any increase in public investment in higher education. Between shrinking youth populations and catastrophic fiscal pressures across most of these countries, there simply isn’t room for expenditures to grow the way they have over most of the past forty years. At the moment, the downward pressure is mostly coming from the United States, and there are some countervailing pressures from newer OECD members (Turkey, Israel and Chile all saw double-digit increases) – but even in the medium term this trend looks unstoppable.

But outside the OECD it’s a whole different story, where the country average increase was 8.4%. Now, some of that was due to inflation, which tends to be much higher in these fast-developing countries than it is here. And the average hides the fact that there is movement in both directions: funding drops in places like Ukraine and Pakistan topped 20%. But the big hitters are furiously increasing spending; in India, a 21% real increase (albeit from a pretty tiny base) and in China it’s 10%. Small players aren’t being left behind, either; Singapore’s increase was close to 30% last year.

Now, we don’t need to get all Lou Dobbs about this. It’s not as though the rise of universities in other parts of the world poses some sort of existential threat to our own schools – the spread of education and knowledge like this is a great thing. But let’s not ignore some of the obvious ramifications. It means increased competition for top faculty, which will drive up prices at the top end of the scale. It means both increased sources of and competition for prestige, which will lead many universities to expand their activities into some very distant parts of the world.

It’s not going to all happen overnight. Many of these countries are starting from a very long way behind our universities in terms of resources, so even with very large annual increases, it could be a couple of decades before they reach western levels of expenditure (and because prestige is a stock rather than a flow, it will take another couple of decades again before institutions in these countries will be seen as broadly comparable to ours).

It will happen; it’s just a question of time. Many more years like 2011, and it could happen a lot sooner than you think.