I’ve made a few key points over the last couple of days:

1) Canadian Universities will be lucky if they keep being able to increase their incomes by 3% per year, holding enrolments constant.

2) The kinds of salary settlements we have seen recently at Canadian universities, if allowed to continue, will eat up easily 70-80% of that income, maybe more, leaving precious little left over for IT, infrastructure, etc.

3) It’s not a problem of administrative bloat. The ratio of academic salaries to non-academic ones hasn’t changed in over a decade.

To put it bluntly, this isn’t sustainable. Things have to change.

Could the solution be on the revenue side? Certainly, that’s part of the current problem. Over the past two years, things have been pretty dire for higher education, with institutions only receiving about 0.45% per year in government funding increases. That might improve a bit in some provinces over the next year or two, but my guess would be that both Ontario and Quebec will see significant cuts in the 2015 budget cycle, once they’ve both had elections. So that’s not in the cards.

Ask students to pay more? That would make oodles of sense in many places (especially Alberta, BC, and Quebec), but it’s a tough sell in a recession. To the extent this is possible, it will be for professional Master’s programs, which are going to spread like mushrooms.

Admit more students? Well, that would work in some places, but not east of the Ottawa River, where things are drying up. International students are always a very viable alternative, though it’s not clear that every institution is equally suited to acting (as Brad DeLong recently wrote in a delightfully bitchy post about the University of California) as finishing schools for the superrich of Asia.

That leaves expenditure – the largest and fastest-rising bit of which is salaries. And here there are only three options: cut jobs, cut salaries, or some combination of the two. Tenure limits institutions’ ability to do the former (to academics, at least), so that suggests that restraint on the salary side is where the action is going to have to be.

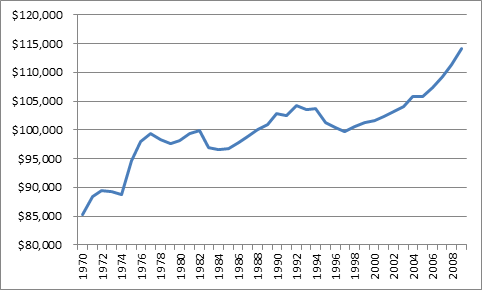

It’s not even a matter of cutting salaries. It’s about getting the rate of salary increase back down to where it historically was for most of the 70s, 80s and 90s. The 2000s saw an historically unprecedented rise in professorial salaries, as shown by Figure 1:

Figure 1: Median Academic Salaries, Canada Real $2012

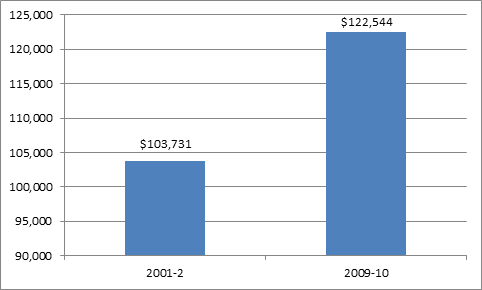

More relevant for university finances was the fact that average salaries were increasing even faster than the median during the 2000s – 18% in real dollars vs. 11% for the median.

Figure 2: Average Academic Salaries, 2001-2 and 2009-10, in Real $2012

You know the good old days everyone talks about? Maybe they were good precisely because salaries weren’t cannibalizing the rest of the budget. Something to think about, anyway.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

All institutions are investing more in research. In part this is a response to the challenge of building reputation. Investment in research is not highly visible, but it is happening through reductions in standard teaching load and the granting of teaching releases for research. So tenured faculty are teaching fewer classes. We see this translated into increased class sizes and increased use of part time faculty.

If we have to cut expenditures, should we not look at the return on investment of this increase in research expenditure? Why must expenditure cuts be directed at students through higher fees, increased class sizes or reduced services?

as much as institutions are opposed to the teaching focused vs research focused institutional categorization, maybe that is the only solution that is efficient and affordable.

What was so bad about all of the primarily teaching-focused undergraduate institutions on the 60’s and 70’s? They produced many of the leaders of government and industry as well as faculty of today.

A tricky problem, so I apologize for a possibly over-simplified solution: caps across the board. Presidents capped at 200k, Provosts at 150k and down through admin ranks. Tenured salaries at 100k. Given that somewhere in the neighbourhood of 50% are part-timers, perhaps half of whom are trying to crack into the TT market – with hires in several areas just drying up – what might be optically unsustainable is paying the big adjunct army ⅓ to ½ of the equivalent to tenured salary for teaching portion of workload for effectively the same job. And, of course, we are not talking here about ABD or fresh-off-the-PhD program instructors either: we are talking folks with over ten or more years teaching at demonstrably high quality.

So, with the capped salary model, increases would be set at inflation plus COL increases. It’s a tough sell for both academic and non-academic staff who might be accustomed to a certain income level.

Restraint can come in a whole rainbow of reforms:

1. Unis can stop paying ridiculously high consultancy fees for stuff that can be done in-house.

2. Instead of erecting brand new facilities, fix up the existing ones.

3. Perhaps a small cut to the athletics

4. Buddy up with other unis to get into joint-purchasing schemes for IT which might reduce per unit costs

5. Put a check on grad program expansion: we are simply not going to “grow” our way out of this; alternatively, put a cap on admissions that is reflective of post-grad employment. This one is a very sensitive topic.

6. Revisit the advertising budget and question if there is any real and meaningful ROI.

7. Investigate what makes SLACs work fairly well, at least according to my data. Is it their focus in not trying to be all things to all people? Slightly lower compensation?

And perhaps the reform that would touch off an enormous, raging, and vitriolic denunciation: revisit tenure. By that I mean the possibility of finding a different way of protecting academic freedom without a job appointment that more resembles a supreme court justice than an average worker. If the uni has a strong enough union shop, that might be suitable enough to prevent wrongful dismissals. This could be coming down the pipe anyway if trends continue, or follow the US model. The sacred cow of tenure is coming up in various US states, and down there where 75% are adjuncts, a lot of them eligible for food stamps, sheer numbers of underpaid teachers may be less sympathetic to the institution of tenure when they are performing many of the same duties teaching-wise as their tenured colleagues for a fraction of the pay and job security of about 4-8 months at a time, without much support.

Alex,

If as you state the ratio of academic to non academic salaries has stayed stable for the last decade then a graph of median or average non-academic salaries should also reveal a steep increase similar to academic salaries. Assuming salary restraint is the direction universities need to go, this would suggest a broader based approach to salary restraint rather than one focused mainly on academic salaries. What about looking at the share of academic and non academic salaries as a share of university budgets and seeing what the trend is also.

Hi Livio. Did that back on Monday (though over a shorter time horizon); https://higheredstrategy.com/how-universities-are-becoming-more-labour-intensive/. Agreed the issue is salaries as a whole rather than academic salaries specifically. Would do the same for non-academics but the typical problem of availability of statistics arises.

I worry that framing this as “average salary” is a distortion of sort. I’d rather see it as a proportion of operating budget used to pay academic salaries. Profs salaries are very much a function of how old they are, and in my experience departments are getting top-heavy. My own department has 50 full time faculty members, of which 3 are tenure track Assistant Professors. So yeah, the average salary is going to look high. Meanwhile, Professors are reluctant to retire, what with the elimination of mandatory retirement in some places, and the hit that defined contributions pension funds took in the last 5 years.

Administrations are surely aware of the significant cost savings they could realize if they could just get some of their older faculty to retire. Yet their actions have had very much the opposite effect – when they refuse to commit to replacing retirees with new probationary-stream hires, they encourage tenure faculty to stay. Instead Administrations seem happier to pocket the recovered salaries when retirements do happen, and use short-term and part-time hires to fill the gap. A 65-year-old Professor would be a lot more likely to step out of the way if there was some belief their Dean would use their salary to hire a new and promising scholar to replace them. It’s not happening, even in high-demand departments where this kind of replacement hiring is warranted.

It might be interesting to see how, say, McMaster or McGill compare to Goettingen or Uppsala: total expenditure per student, government funding, external research $, tuition (for domestic students), and median faculty salaries.

I would be willing to bet that McMaster and McGill would be higher than Gottingen and all those categories (except possibly govt funding). They would *definitely* be second to Uppsala in gov funding but would probably lead in every other category.

I think a much more detailed analysis, while probably not possible, would be useful. There are several things that have happened over this time period.

As mentioned above, we have an aging professoriate, but we have also had more emphasis placed on hiring world-class scholars through the CRC and other programs which have put upward pressure on salaries to attract this talent (as reflected in the second chart).These programs were in large part due to the fear in the mid-1990s that Canada was losing her “best and brightest” to the US and other countries and that we needed to attract and retain this talent in order to be competitive globally.

How has the composition of faculty changed over this period? Have business and other professional schools (along with their higher-than-average salaries) expanded over this period in response to demand for these programs? I suspect so. I doubt these numbers would look the same if the salaries were limited to those in the arts and sciences.

Further, it is common to look at the inputs into the university production equation (since these are easy to measure), but what about the outputs? Surely systemically we are producing more students (although I won’t comment on quality) as well as more research than ever before. Indeed, it is my understanding that Canadian research productivity ranks among the highest in the world per faculty member.

Salaries have increased for faculty, certainly, but so have the expectations regarding our teaching and research. Today we are much better teachers and more productive scholars than the faculty who taught my generation. Many of my professors came into the Canadian PSE system in the early 1970s in response to the expansion of PSE in Canada at this time, and several published little to nothing over their careers. This hiring spree is nicely reflected in the first chart which shows that median salaries increased by about 16% in real terms from 1970 to 1976 (from about 85k to abut 99k), which is higher than the approximate 15% increase from 1976 through 2009.