I am sure most of my readers are aware of the Biden Administration’s plans to forgive student loans. However, what may have gone under the radar is the way the current administration is staking a lot of money on an attempt to re-build the country’s student loan system.

The basics are this: the Democrats want to make student aid repayment easier in three ways. The first is by raising the repayment threshold – that is, the income level at which students must repay student debt from 150% of the official poverty line to 225% of the line (very roughly, from a bit over $20,000 US to a bit over $30,000 US, which is about where our repayment threshold is). The second is that they also wish to reduce the maximum rate of repayment above that level from 10% to 5% (for undergraduate loans, at least; graduate loans would stay at 10%). The third is that for anyone under the threshold, government will pay the interest so that loans will not face accumulating interest (Canada has been doing this for 40 years, and it’s a major reason our loan system works so well). And, for those loans under $22,000, forgiveness will kick in earlier than the current 20-year mark, bottoming out at just 10 years for those with debt of $12,000 or less (which would include a very substantial fraction of those earning associates’ degrees).

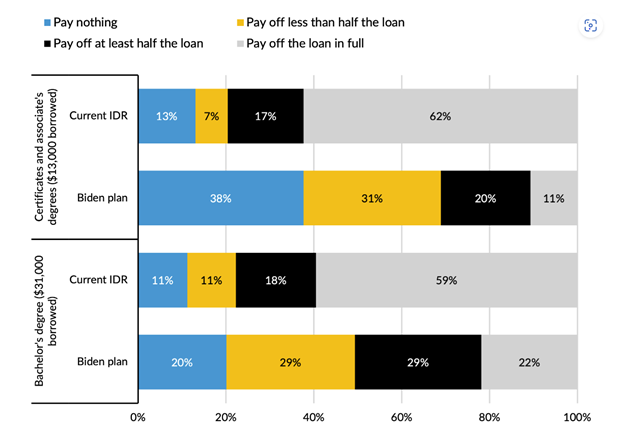

Now, the basic upshot of all these changes is that by design most students will not pay back their student loans in full. Just do the math. Someone with a $60,000 income will only be required to $1,500/year in student loans, or $125 per month. That would be enough to repay a loan of $19,000 over 20 years, but for something close to the median loan – say $30,000 – it would leave at least a third to be forgiven at the end of 20 years. That’s pretty generous! In fact, according to an analysis done by a group of authors at the Urban Institute in Washington, only 11% of borrowers with typical debt levels at the associates level and 22% of those at the bachelor’s level would be expected to pay off their loans in full; meanwhile 38% and 20% of those with typical debt levels, respectively, would pay nothing at all.

The political logic here is clear. If you can’t get budgetary approval to increase Pell grants, use executive authority to alter the terms of the loans so that they become something close to a grant, at least for a large number of student borrowers. The nominal debt exists, but in practice borrowers will enjoy low capped monthly payments and generous forgiveness so that in fact there won’t often be a link between what is owed and what is paid. Political winner, right?

Not so fast. There is another country that dreamed up a plan something like this: high fees, high debt, but generous loan thresholds and forgiveness such that – at one point (rules have changed a bit since) – well over 70% of total debt was expected to be forgiven (it’s now around 50%). And that is the United Kingdom. The UK’s loan repayment threshold and repayment rate are a little bit higher than the US, but in broad outline the proposed US program is almost indistinguishable from the one the UK has been running since 2012.

Dear reader: would it surprise you to learn that the UK loan system is not in the least bit popular? That despite its clever design in which the poorest graduates pay nothing or very little, everyone focuses on the size of their initial debt (roughly £45,000 or C$76,000 at PPP) and not the generosity of the repayment exemption?

In short: the Biden plan will, without a doubt, make life easier for students, though at significant cost (the Biden administration makes it out to be $138 billion over ten years, which is roughly as much as combined Canadian provincial expenditures on universities and colleges over the past ten years). But will it make Democrats popular? Probably not. The policy instincts at work are correct it, but the comms problems are likely to overwhelm it.

One Response

the SL proposed by the USA sounds like one of those psychological problems in which we value lower debt or the perception of lower debt as opposed to actual lower debt but just a little later.