Time was – say, for the thirty years or so after Vannevar Bush wrote Science: The Endless Frontier – everyone had a pretty good understanding of what was meant by the term “research”. Basically, it was the stuff that pointy-headed people did in labs and was the opposite of “development”.

Figure 1: Ancient Understanding of Research

But then, people on the development end got a bit snippy. They, too, did research, it just had a more focused sense of practical use than did the work of the lab-eggheads. And so, we ended up with a slightly altered understanding of research, shown below.

Figure 2: Slightly Less Ancient Understanding of Research

Figure 2 reflects how policymakers in Canada think about research. There is the curiosity-driven stuff on the left, and the use-driven stuff on the right and – from the policy perspective – the question is how to get the balance between these two right so that the line continues into “product development/innovation” and then “productivity/middle-class jobs”. Yes, it’s a worldview which completely ignores process innovation and disastrously conflates science policy, innovation policy and growth policy (all of which should be conceptually separate), but it’s what we’ve got.

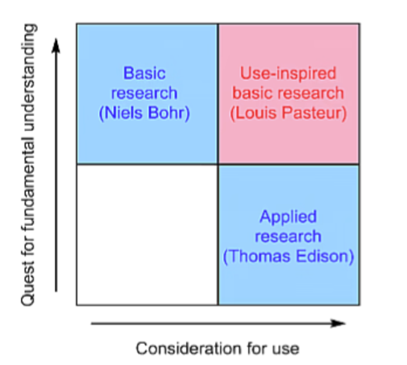

Much of the rest of the world moved on to another definition in the 1990s to a theory known as “Pasteur’s Quadrant”, after the book of the same name by the late Donald Stokes. The quadrants are based on Stokes’ insight that research needed to be plotted along two axes: a quest for fundamental understanding, and consideration of final use. This gives you three potential research types: Basic Research, like that of theoretical physicists like Niels Bohr, Applied Research close to industrial applications like that of inventors like Thomas Edison, and a third group known as “use-inspired basic research” like that of French microbiologist Louis Pasteur.

Figure 3: The Quadrants

In truth, Stokes’ typology is less helpful as it applies to individual research projects than it is to clarify the differences in how various scientific fields approach basic research. Cosmologists are looking for “fundamental understanding” when they do research, but for fields like Engineering and Medicine, considerations of use are never far away and much of their work ends up in the Pasteur quadrant almost as a matter of course.

But in the past couple of decades, a new and completely different meaning of Applied Research has drifted into general usage resulting from the advance of research activities in colleges and polytechnics. Originally, the term was used to denote the work these institutions did with local businesses to help them improve industrial processes – very much the definition of “applied research” in figure 2. But over time, I can’t help but notice that these institutions have broadened the use of this phrase to cover almost anything they do which isn’t traditional teaching.

This isn’t just a Canadian thing – I was at the annual conference of the World Federation of Colleges and Polytechnics in Spain this past June, and virtually everyone was doing it. Capstone projects for graduating students? Well, it is research, and it has an application, so it must be “applied research”. Simulation training for cyber-security professionals? Well, the simulation is an application of research, right? So, it must be applied research.

In fact, the main way that colleges/polytechnics seem to talk about “applied research” these days has more to do with innovative methods of training than actual discovery. “Applied research” often means advanced simulation techniques and more life-like teaching settings (for instance, check out the Victorian Tunnelling Centre at Holmesglen College in Melbourne – amazing stuff and one can only imagine how much better life in Toronto would have been if we’d one of these before extending the Downsview line or starting the Eglinton LRT). Sometimes it simply includes advanced training for industry, or co-located facilities which double-up as both centres for applied research for students and training facilities for industry (for example, Red River College’s Stevenson Campus).

I suspect this shift has something to do with the politics of funding. In Canada, the federal government spends about $6 billion on a year on transfers to institutions (i.e. not including the Canada Social Transfer Post-Secondary Allocation or the Canada Student Financial Assistance Program), 92% of which goes to universities rather than colleges. Because most of this money is for research, colleges figure they will have an easier time trying to get funding out of Ottawa if they describe everything they do as some form of research rather than the hodge-podge of activities it is. That and all the “parity of esteem” stuff.

But here’s a thought: why not just call a lot of these initiatives what they are, that is, advanced technical skills development? As we head into a few decades where the unemployment rate is likely to be 5% or less and businesses complain incessantly about skill shortages, the need for advanced skills training facilities is blatantly obvious. Historically, all our training efforts have been about creating more skilled workers – but in our current demographic dilemma, that’s just not on. What we need are much better workers. And that means better training and better training facilities infrastructure, something Ottawa could choose to fund on a permanent basis on a basis much like the Knowledge Infrastructure Program or the Strategic Infrastructure Fund, if it chose to do so.

In other words: ending the linguistic creep of Applied Research isn’t just good for the English language, it’s also very good policy.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post