A very good Statscan report came out last week, and didn’t get nearly enough attention. Authored by the excellent Marc Frenette, it’s called, An Investment of a Lifetime? The Long-term Labour Market Outcomes Associated with a Post-Secondary Education, and it deserves a wide readership.

What Frenette did was link the 1991 census file to the Longitudinal Worker File (LWF), which integrates data from Records of Employment, annual T1 and T4 files, and some data on employers as well, for a 10% random sample of all Canadian workers. From this, he created a sample of about 8,000 people who were born in Canada between 1955 and 1957 (i.e. who were about 35 years old at the time of the census), and who held jobs in 18 out of 20 years since then. From this, he worked out what the added value of university and college credentials were over that period.

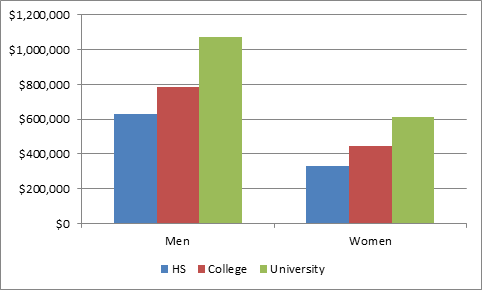

Figure 1 shows earnings by education level. For men between the ages of 35 and 55, the added benefit of a college education (vs. high school) was $153,000; for a university education it was $445,000 (for women, the figures were $115,000 and $280,000). In addition to higher salaries, higher levels of education were also associated with higher levels of union membership, and lower frequency of layoffs.

Figure 1: Net Present Value of 20-Year Earnings of Canadian-Born Workers, by Level of Education

Figure 1 isn’t exactly ground-breaking; more education = more money, and more so for men than women. Where it gets interesting is when the results are disaggregated by gender, and attention is paid not just to means and medians but also at the distributional tails. Figure 2 compares the wage premiums at various percentiles for female college and university graduates, over high school graduates in the equivalent percentiles.

Figure 2: Cumulative Additional 20-Year Earnings for Female College and University Graduates, at Selected Percentiles

Figure 2 shows three things. First, women with university degrees make more money than those with college or high school across all percentiles. Second, that said, down around the 5th-10th percentile, the premiums are so low that it’s really not clear that women are better off with higher education. And third, the premium for higher education really flattens out above the median – which, as Figure 3 shows, is not even vaguely the case for men.

Figure 3: Cumulative Additional 20-Year Earnings for Male College and University Graduates, at Selected Percentiles

Crazy stuff. Recall from Figure 1 that average gains for men were significantly higher than for women. But Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that the median gains – those at the 50th percentile – are about the same. The difference is that among males, the top ten percent – and especially the top five percent – are reaping astronomical rewards from higher education.

The last amazing thing in the paper has to do with how men and women with bachelor’s degrees fare comparatively in the public and private sectors. And the numbers there are astonishing: in the bottom ten percentiles in the private sector, women are making less money, cumulatively, than their counterparts with just high-school education. But what’s really interesting here is the fact that in the public sector, at least, women actually reap higher gains than men.

Figure 4: Median Cumulative Additional Earnings for Male and Female University Graduates in Public and Private Sectors

Nitpickers will likely snub this study – it deals with a cohort that finished school 35 years ago, it doesn’t disaggregate by field of study, etc. But methodologically, it points to ways to conduct future studies (we could do the same with a shorter period for 25 year-olds in the 2001 census, for instance), and substantively it gives us a lot to chew on, not only in terms of average earnings, but also with the distribution of those earnings. Kudos to Marc for this work.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Interesting information. If women left paid employment to raise children, would this effect these statistics? Does that account for some part of the gender differences?

Hi Pamela. For both genders, they had to be in the LF for at least 18 years since 1991, so if they left the labour force for more than two years, they were excluded from the sample. That means” i) no, it does not account for gender differences and ii) in reality, gender differences are larger than portrayed here.

Thanks again for alerting us to this wonderful piece and particularly for highlighting its methodological importance. Without denying all that, I feel I would be remiss if I didn’t raise a point concerning any study which claims to quantify the benefit of a post-secondary education. I don’t deny great benefit (in economic, social, personal and many other terms). However, such numbers are often used in arguments for higher tuitions and other such policy opinions. Some of the dis-aggregated and ‘tail’ data here could serve to make those conversations more complex and interesting.

However, I must point out that the characteristics of people who went to university in the 1970s may well be very different from those who did not. Those personal attributes and social context differences could well have contributed to differences in earnings as well. The difference between earnings of university graduates compared to high school graduates does not tell us the incremental value of higher education because the characteristics and contexts of the two populations were very different, particularly in the 1970s! To know the incremental value of higher education we would need to know what those same university graduates WOULD have made (given their personal and social contexts) if they’d not gone to university. Of course, that’s data we can’t get. But, it is not unreasonable to predict that those people, with whatever advantages and attributes they might have possessed which put them in university in the 1970s, would have also fared better than many in the workforce if they’d not gone to university. So, please be careful when claiming the dollar value of an education.