Yesterday, we talked about the Shanghai Subject rankings. Today I want to switch over to the Times Higher Rankings. Not their flagship World University Rankings, because those are basically a slightly more sophisticated version of ARWU’s bibliometrics with a popularity survey attached (plus a little bit of institutionally-supplied data about research income and internationalization). And from a Canadian perspective they always provide pretty much the same story: Toronto 1, UBC 2, McGill 3. I want to focus on a more interesting story: the THE’s Impact Ranking, which has now gone through four iterations and which now features four Canadian institutions in the world top-10.

The Impact Rankings are a genuinely new type of ranking. It’s meant to be an alternative to traditional rankings which privilege research output, by examining how much institutions contribute towards the seventeen UN Sustainable Goals. Thus, it’s not actually one ranking, it’s 18 separate rankings: one for each of the seventeen UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and one summary ranking. The summary is a composite of each university’s best three ranking results from SDGs 1-16, plus its results on SDG 17 (Partnership for the Goals).

Here’s where it gets a little odd. Usher’s First Law of Rankings says that the more interesting the concept being measured by ranking indicators, the harder it is to procure useful, consistent data across institutions. And believe me, these are some interesting concepts. To measure these, THE has come up with 232 different indicators, only about a third of which are based on standard, quantitative data such as bibliometrics or graduation numbers (i.e. share of graduates coming from a particular subject), or objectively measurable things like food waste. The other two-thirds of the indicators are 100% subjectively assessed. THE asks institutions to submit evidence on issues such as whether they have sustainable food choices on campus, or whether it provides a neutral platform for political stakeholders to discuss various types of challenges. Universities submit a portfolio of evidence to show that they can, each gets graded according to a rubric that THE does not share publicly and voila! Scores that can be combined into ranking.

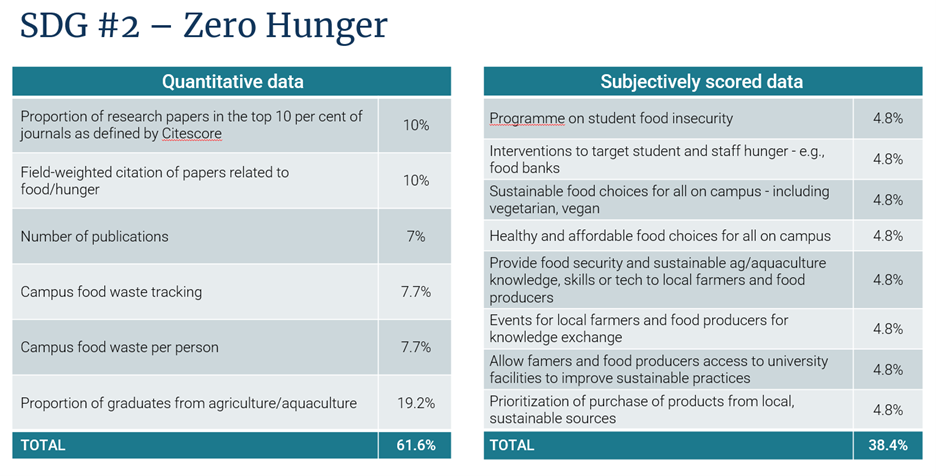

Just to get a flavour of how different these indicators are from what you usually see, here’s the list of indicators for SDG #2, “Zero Hunger” (one that Canada does very well in – Queen’s #1 globally, Alberta #2, and Laval #4). The quantitative elements are weighted more heavily than the subjective ones (in 13 out of 17 SDGs, they make up 50% of the weighting) but as you can see, the majority of the individual indicators are subjectively scored.

(You can see the full list of indicators for each SDG here.)

Three questions emerge from this.

- Is this a real ranking what with all the subjective data scoring? Look, it’s pretty clear that a lot of the points come from creating portfolios of information which “tell a story”, and institutions are getting ranked on how well they tell that story. You might think this to be offensive from a scientific/data point of view, and yes, it’s deeply opaque (universities do not get feedback from THE as to why they received the mark they did on each indicator). But “judge us by our stories!” is exactly what universities have been asking for from rankers for decades. So, you know, be careful of what you wish for.

- Holy crap – 232 indicators? This looks like a lot of work. Why would any institution sign up for this? There are two points of view on this. The first is that institutions aren’t required to put up data on all those indicators. Fifty of them are bibliometric indicators, which THE collects itself. As for the rest, institutions aren’t required to submit data on all 17 SDGs – you can enter with as few as just four, which might mean as few as twenty-two indicators requiring data indicators depending on which SDGs are chosen. And the data each institution collects must be from the last five years, which means that new data collection in any given year is not necessarily that big a deal. Second, over half of the Canadian institutions who participate in THE provide volunteer to provide the maximum amount of data and submit in all 17 SDG categories. Partly they do this because they genuinely don’t know in which categories they will do best, but partly it’s because many institutions have a commitment to sustainability, and they find that collecting this data is a good way of holding themselves accountable on the issue. So, yes, it’s a big deal, but one that many institutions find well worthwhile.

- Why do Canadian institutions do so well in theses rankings? Let’s be clear: Canada does not just do well in these rankings: we dominate them. Queen’s is in third place overall; Alberta, Western, and U Victoria are all also in the world top ten. We also make up ten of the top 50 and 16 out of the top 100 worldwide. And we’ve been getting better over time: in year 1 only one of the top ten was Canadian. And there is a lot of movement in these rankings, presumably in part because so many new institutions are joining the rankings each year. McMaster and UBC, for instance, were #2 and #3 in the world in 2019; today they are #33 and #26. It’s not the bibliometric data that’s shifting: it’s quite clear that the bar is moving on the subjectively scored data.

One reason we do well is that a lot of universities – in particular high-prestige research-intensive universities – choose not to participate in this ranking precisely because they are not guaranteed to do well based on their research output (kudos to U of T, which participates even though it comes 99th). Indeed, so little does research output count that this year’s world #1 is Western Sydney University, which might make the top 15 research universities in Australia. Put simply, a lot of the institutions we would traditionally think of as peers and competitors simply don’t show up (I am pretty sure a lot of the big US land grants would do well in this ranking, and I am not sure why they don’t take part) and their absence makes our ascendence easier.

The second reason is that the whole “telling our story” thing is something that universities in Anglo-Saxon countries do well. This is due to their relatively marketized funding sources that require them to spend more on marketing, comms, and government/community relations than the rest of the world’s universities combined – are really good at. We have more resources to throw at problems like these and we share a language with the people who are doing the marking at THE HQ (that’s a real issue with these rankings – 76 of the top 100 come from a country where English is an official language, and I suspect that’s not all down to which institutions choose to participate). So, to some extent this kind of ranking speaks to a core competence of putting out best foot forward.

The third reason is that maybe – just maybe – the story we can tell is better than the ones others have to tell. Maybe Canadian universities are, genuinely, well above average at connecting with and translating knowledge into their communities. It’s easy to see what that might be the case – outside North America, most of the world did not think of this kind of activity as core to the identity of universities until relatively recently: the notion of “flagship” universities deeply embedded in their communities barely existed outside of North America until the 1980s. And in the past decade or so, several Canadian institutions have made serious commitments on sustainability, and they have achieved some impressive results.

My advice to institutions on this ranking is this. First: get involved if you aren’t already. Being a research powerhouse is not a barrier to doing well on these rankings. Second: don’t try and cherry-pick your SDG rankings. Enter as many categories as you can, and all of them if possible. Chances are you have no idea which ones you’re good at and which you are not. And third: don’t be intimidated by the potential workload. There are likely a lot of people on your campus who can be mobilized to help tell stories about how well your institution does on various metrics (and if you need some help on this, feel free to contact us at HESA, we can help).

In sum: the Impact Rankings are a strange beast, one in which Canadian institutions seem to do well both because we do good, and because we are adept at articulating that good. Given the reputational stakes involved, it seems like the one ranking where institutions would be well advised to spend more time and resources.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post