Over the past few days, I’ve been providing a lot of data on how well global “world-class universities” are faring (briefly: most of them are doing pretty well, the ones in Canada much less so). But to some degree the real question is: does any of this matter? Do higher expenditures per student actually result in greater academic output? And if not, why not?

To answer this question requires a quick detour into the issue of bibliometrics. If you try to measure publications over time, one thing that becomes clear is that there are lots more indexed publications out there than there used to be. Part of this has to do with the fact that more journals are being published (the spread of open access journals is a big deal here), part of it is that the big indexes – those managed by Clarivate (formerly Thomson Reuters) and Elsevier – are doing a better job of covering the universe of journals. So one can’t just look at whether institutions are publishing more: across all the top 200 universities in the Shanghai rankings, between the periods 2006-09 and 2012-2015 (periods for which we have very good publicly-available data thanks to the folks at the Leiden research rankings), the average institution saw the number of publications rose by 42%, and only one institution – Tokyo Tech – failed to increase the number of its publications.

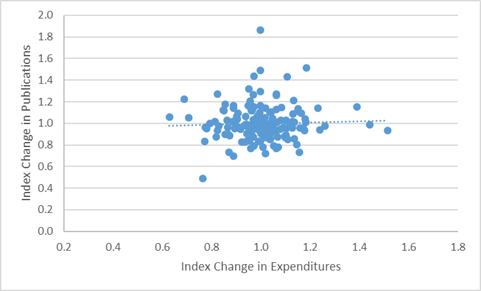

What one can legitimately ask, however, is whether proportionately larger increases in expenditures lead to proportionately larger increases in publications. So, in the graph below, what I do is plot relative increases in publications (i.e. normalized for the overall average increase of 42% in publications) versus the relative increase in institutional funding (i.e. normalized for the overall average increase of 15.7% in institutional per-student expenditures). And what we find is, basically, there is no relationship between the two.

Figure 1: Change in research publication intensity as a function of change in real per-student expenditures, ARWU-200 universities, 2006-09 to 2012-15.

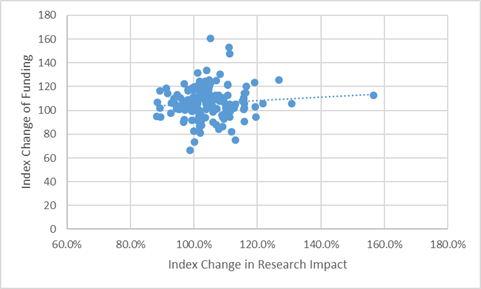

This result is perhaps surprising, but of course number of publications is simply a measure of quantity, not quality. Perhaps if we used a measure of quality, such as the percentage of papers which make the global top 10% in terms of citations (normalized for field of study, obviously), we would see a difference?

In a word, no. It’s more or less the same story: extra money at the margin does not appear to lead systematically to higher-impact papers.

Figure 2: Change in research publication impact (% of paper making the global top 10%) as a function of change in real per-student expenditures, ARWU-200 universities, 2006-09 to 2012-15.

Now, to be clear, these figures don’t quite mean that money doesn’t matter. Obviously, richer universities tend to produce more research than poorer ones. But as we saw on Tuesday , institutions in the top 200 vary widely in their financial capacities, and those at the top (eg. Caltech) have an undeniable advantage over less-rich institutions in publications in absolute terms. If you could wave a magic wand and give – say – Université de Montréal a million dollars per student instead of the $30,000 or so which it actually has, then you’d probably see a significant increase in output and/or impact.

Strictly speaking what this means is that over the short-to-medium term, incremental shifts in funding don’t move the needle very much. At the margin – which, in the real world, is how institutional income progresses – increases in expenditures don’t matter that much, at least over a five-to-eight-year horizon. Over a longer time-horizon it might make a difference, but we don’t have the data to test this proposition.

(Also, keep in mind that the global data excludes China because we have no funding data for them prior to 2012 – and the increases in output and impact there have been spectacular over the past few years. If we could include those institutions, the relationship might look a little stronger.)

But the larger point here is that even though money doesn’t matter in the short-term, that doesn’t mean that improvement is impossible. In fact, improvement seems to happen all the time. It’s just that it happens through better use of resources and better management, not an increase in resources. That’s a lesson everyone should take to heart.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post