One of the things that I find extremely worrying about higher education policy these days is that we’ve simply stopped talking about increasing access to the system. Oh, sure, you will hear lots of talk about affordability, that is, making the system cheaper—and hence arguments about the correct level of tuition fees—but that’s not the same. Even to the extent that these things did meaningfully affect accessibility (and it’s not at all clear that they do), no one phrases their case in terms of access anymore. We don’t care about outcomes. And I do mean no one. Not students, not governments, not institutions. They care about money, cost, all sorts of things—but actual outcomes with respect to participation rates of low-income students? At best, they are a rhetorical excuse to mask regressive spending policies which benefit the rich.

This is a problem because it now seems as though the process of widening access, a project which began after World War II and has been proceeding for seven decades. And yet, as some recently-released Statistics Canada data shows, participation rates are now actually in decline in Canada. And it’s mainly because growth at the bottom has stalled.

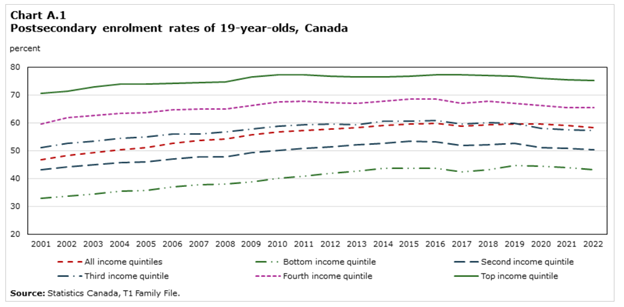

Below is the chart StatsCan released last month. It shows the post-secondary enrolment rate for 19-year-olds, which I will henceforth refer to as the “part rate” or “participation rate,” both for the entire population (the dotted red line) and by income quintile.

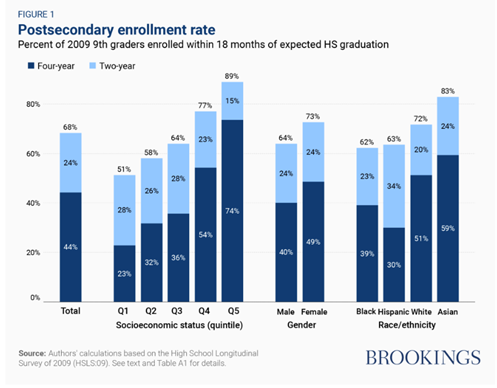

Now, the first thing you may notice is that there are some pretty big gaps between the participation rates of youth from rich and poor families; the top quintile does not quite attend at double the rate of the lowest quintile, but it’s close. And you might be tempted to say, “Hey, I’ve taken Econ 101—That must be because of tuition fees!” Except, no. These kinds of part-rate disparities are pretty common internationally, regardless of tuition fees. Here are postsecondary enrolment rates by income quintile from the United States, which, on the whole, has higher fees than Canada:

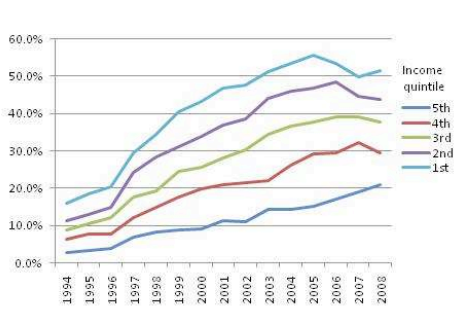

And here’s a similar chart from Poland, which mostly offers education tuition-free:

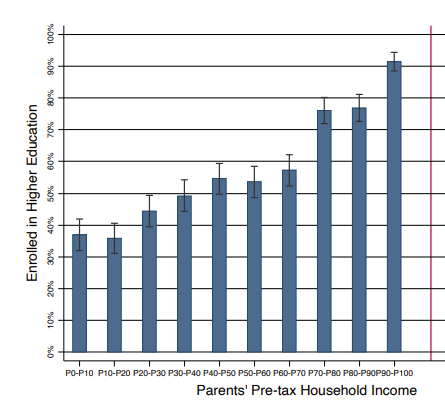

And here’s one from France, where public universities are tuition-free but students are increasingly heading to the fee-paying private sector:

I could go on, country-by-country, but I will spare you and instead point you to this rather good paper doing a cross-national analysis across over 100 countries by OISE’s Elizabeth Buckner. Trust me, it’s the same story everywhere.

But let me point out what I think are the two important points in that chart. The first is that the red dotted line, which represents the participation rate of all 19-year-olds, basically plateaued back in about 2014, the first year it broke the 59% and is currently headed downwards. This is a huge change from the previous period, 2000-2014, when overall participation rates rose from 46% to 59%. First growth, now stagnation.

The second is that during the growth period, the biggest strides were being made at the bottom end of the income scale. The part rate gap between top and bottom quintiles fell from 38 percentage points in the early 2000s to about 32 percentage points in 2014, even as part rates for the wealthiest quintile increased. That is to say, more of our growth came from the bottom than from the top. That’s good! But the growth stopped across all income quintiles and went gently into reverse for the top four income quintiles.

Now, you might think that it’s not a bad thing that participation rates peaked, that maybe we were in a situation where we were overproducing postsecondary graduates, etc. Who knows, it’s possible. I don’t know of any evidence that would suggest that 57-59% of the youth population is some kind of hard maximum, but if stipulating that such a maximum exists, then it might well be in this range.

But since it’s quite clear that this overall plateauing of participation is happening entirely by way of freezing educational inequality at substantial levels, being OK with the present situation means being OK with major inequalities, and in any democracy which wishes to remain a democracy, that’s not really OK. It is true that, as I noted earlier, disparities are the global norm, but that doesn’t mean you don’t keep up the struggle against stasis. It might be the case that there is some kind of “natural barrier” to keep the country’s PSE part rate at 57-59%, but in what world does a “natural barrier” keep those rates at 75% for rich kids and 43% for poor kids?

Increasing access overall and narrowing rich-poor access gaps is incredibly difficult. If it were as simple as making tuition free, we’d have it licked in no time, but countries with free tuition don’t have noticeably narrower part rate gaps than those that charge fees. Achieving these gaps requires a whole suite of policies to narrow educational achievement gaps as well as financial ones, to offer young people a variety of flexible program types rather than an inflexible academic monoculture and to ensure that advice and support exist for students not lucky enough to be able to access the kinds of cultural capital available to the top quintile.

As I say, achieving success in this area is very difficult: solutions are neither easy nor quick. But what makes the problem even more intractable is ignoring it the way we are doing right now. Are we a country that actually cares about equal opportunity? Or is that just a myth to which we genuflect when we wish to pretend to be more socially progressive than Americans? I lean towards option #2 but would be overjoyed to be proven wrong.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One of the books I have on my shelf is Who Goes? Who Stays? What Matters?, a collection of papers that you and several others edited in 2008 and which leaned heavily on the then-current Youth in Transition Survey data.

The conclusions you cited about access to PSE in the introduction to the book were essentially that “culture matters more than money”, that access depended heavily on family background, early schooling experiences, parental education, and ultimately personal aspirations that were in turn derived from the former circumstances.

As the K-12 system continues to decline in quality, its raw material is more and more discouraged by the process it is undergoing (as are its parents), and less and less able to see the larger point in continuing with education when it doesn’t appear to offer anywhere near the social and economic mobility it once did.

When the raw material is spat out at the end of the compulsory 12 years it is even less prepared for PSE than ever; I remain curious about patterns of persistence and the sheer amount of time and money-intensive backtracking and “remedial education” that are required to get a decent fraction of the first year cohort into the second and beyond.

But there is little to no Canadian research done on this that I’ve been able to find (the US DoE has done quite a bit of this and it’s shocking; however, it won’t be shocking for much longer because there will be no more DoE, and therefore no research).

2008 was 17 years ago – since then the inputs into the PSE system are even poorer in quality: less motivation and encouragement from exterior sources; more distracted; less prepared and resilient, and finally, less convinced of the payoffs for being there.

Of course financial factors are always there, but as you et. al. pointed out in the book, they are most important for those at the margins. Perhaps the margins, while persistent, are narrowing.

Buckner et al’s article “Wealth-Based Inequalities in Higher Education Attendance: A Global Snapshot” is available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.3102/0013189X231194307 (the link provided in the blog post doesn’t work because it’s missing the “h” at the beginning of “http:”). As informative as the article is, it doesn’t pinpoint which countries have been able to encourage higher rates of postsecondary participation. It would be interesting to know if countries such as Sweden, Norway and Denmark perform better in this regard and, if they do, what they’re doing to facilitate higher rates of participation.

I was about to write a longer response, but brtrain has said most of what I would, only better than I could.

I’d just want to add that changing “family background, early schooling experiences, parental education, and ultimately personal aspirations that were in turn derived from the former circumstances” is peculiarly difficult. Most people do something like what their parents did in life. How does one convince students from lower income backgrounds to dedicate time and money — not only tuition, but living expenses and deferred work-lives — to get a higher education?

There have been basically two solutions tried, neither convincing:

1. Emphasize the financial payoff.

2. Try to teach whatever you think members of lower-income groups (and groups associated with lower income) want to learn.

The first increasingly doesn’t seem to figure, and in any case, it prostitutes education to job training. The second seems phony, and denies students access to the sort of liberal education which would actually provide cultural capital. Neither is likely to convince a kid whose vision of the good life is working on cars all day like his Dad to become interested in arts and sciences.

In sum, it doesn’t seem that access is a problem, even if participation is. It isn’t that students from lower-income groups can’t go to university, but that they don’t.