As most of you know, UK tuition fees more or less tripled this past year. The initial applicant/enrolment data from a couple of months ago (which I covered, here) indicated that applications fell by about 8%, but also that the drop came almost entirely from older students (among traditional-aged students, the drop was just 1%). Worrying, but not apocalyptic.

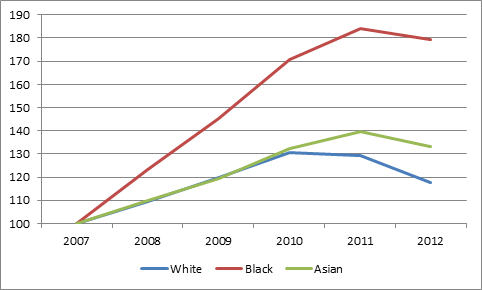

Last week, two new interesting pieces of data were released. The first was application data by race; though Black and Asian (i.e. Indian & Pakistani) students were often thought most vulnerable to changes in fees, data suggests they were actually less affected by tuition fee increases than were Whites. This year, applications from Whites were down almost 9%, compared to 2.7% for Blacks, and 4.4% for Asians. With respect to accepted applicants (see here for more information), the picture is essentially the same, except Blacks actually register a slight increase. Part of the explanation is likely that mature students – the ones most affected by the tuition hike – are just a lot likelier to be White than Black or Asian. Regardless, it’s not the nightmare outcome many predicted a year ago.

UK domestic applications by race (2007=100).

The other new data is on institutional enrolments. If you’ve read any English higher ed news in the last 72 hours, you’ve probably seen headlines about “wild fluctuations” in applications and enrolments. This seems overdone to me. Yes, the decision to make students pay more did change applicants’ behavior. But the average university in England always gets about six times more applicants than it has space for, so even if applicant numbers drop by 20% (which they did at a dozen or so universities), keeping accepted applicants (and, hence, paying customers) at roughly the same level isn’t difficult, as long as you tweak your admissions formula slightly so as to get a better yield. Anyone with major fluctuations in new enrolments simply blew their yield calculation.

The University of East Anglia, for instance, saw a 14% drop in applications, but still had an entering class 1% bigger than the previous year. Others were simply less lucky, or less astute, in calibrating their yields. Bradford, for instance, saw an 18% drop in acceptances, even though applications only fell 4%.

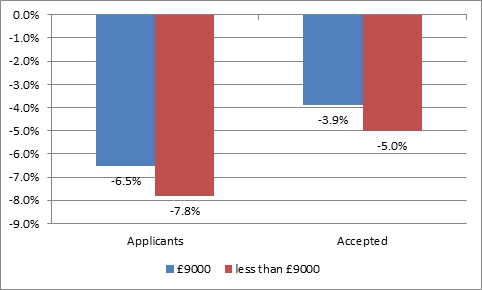

But the big question: did schools that raised their fees to the full £9000 do better or worse than those who kept their fees somewhat below that cap? Well, for the 117 public universities with over 1000 applications per year for which I could find both enrolment and fee data, the results can be seen below. There’s nothing obvious which indicates that higher fees make students go bargain-hunting, and that’s is probably why many institutions are thinking about raising their fees again, next year.

Average Institutional Change in Applications and Acceptances among UK Institutions, by Minimum Tuition Fee, 2011 to 2012.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Dear Mr. Usher,

Two other factors that might yet affect institutions in the UK. First, it appears that inter-regional flows (ie Wales – England) might have been changed by the new fee structure. Wales looks to have been worst affected, as Wales-domiciled students took advantage of a generous (and portable) subsidy from the Welsh Government to go to an English university. Second, the market is currently very constrained, with fees capped at £9K and places strictly capped too. The latter, however, is gradually changing as quotas on the recruiting of top-ranked school graduates being lifted. Top UK universities are rumoured to be planning signifcant expansion of undergraduate places on that basis. That might rob lesser-ranked institutions of students – who under a quota system often find themselves taking their second-choice university

Hi Steven. Thanks for reading our stuff.

Good point, particularly re: regional flows. A couple of welsh institutions did indeed get hammered (Aberystwyth in particular), but Cardiff seems to have done quite well (acceptances up 13%). The effects on Scotland appear quite interesting as well.