For the last few weeks, I’ve been giving you little snippets from World Higher Education: Institutions, Students and Funding. Today, I want to address a topic that came up in the document’s webinar launch (available at the University World News’ YouTube channel). It’s something I haven’t really been able to talk about because it’s something that didn’t appear in the report for the simple reason that it didn’t happen. It is, to some extent, the dog that didn’t bark. But as in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s tale, sometimes something that didn’t happen is as important as something that did.

Cast your mind back to the late 1990s and 2000s, when we entered the takeoff point for the massive increase in participation seen across the Global South. Three things were taken mostly as a given for how broadening access in the Global South would take place:

- Private education institutions were going to bear a big part of the load of enrolment expansion. We knew this was going to be the case because of the role they had played in the expansion of access in Latin America, East Asia and especially in the transition economies of the former socialist bloc in Eastern Europe.

- Public institutions would gradually become less dependent on public financing sources. Partly, I think this was because the expansion of private education was assumed, and it was similarly assumed that the public would not tolerate a major gap in pricing. But partly I think it was assumed that anglophone countries and places like the Netherlands would act as models – who wouldn’t want their universities to have all the extra funding that tuition and other forms of private income provides?

- Student loans were going to play a key role in the expansion of access, because they would make the introduction of fees easier. Here, Australia (1988), New Zealand (1993) and the UK (1998) were all seen as successful cases where left-wing (ish) governments had found ways for higher education to co-exist with the market and significantly increase access at the same time.

As I say, when I got into the business, this was all received wisdom. But if there is one thing that our World Higher Education shows, it is that precisely none of this actually happened in the period 2006-2018.

Let’s start with private higher education. Did it grow in the Global South? Yes. Faster than public education? Also yes. But not by much. Back in 2006, 21 million students in the Global South were in in private higher education institutions; in 2018 it was up to nearly 47 million. But in percentage terms, the growth was barely noticeable: 31% in 2018 vs. 27% in 2006. Most of the load of increasing access fell on public institutions.

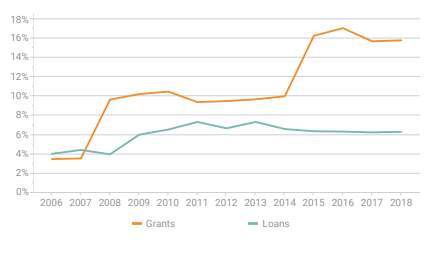

Then there are student loans. As Figure 1 shows, they did increase in scope in the Global South. In absolute terms, the number of students loans nearly tripled from a little over 3 million in 2006 to around 9 million in 2018. But over half of this increase came from China, and across the Global South as a whole, only 6% of students have access to a loan. So the expansion of access isn’t being financed through loans.

Figure 1: Share of Global South Student Body Receiving Grants and Loans, 2006-2018

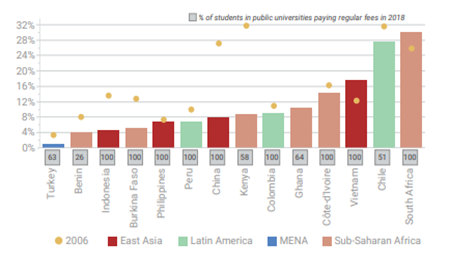

And why aren’t loans being used? After all, something on the order of 90% of students in Global South are paying some kind of fees. Well, in most countries of the Global South, tuition fees are falling as a percentage of per-capita GDP: that is to say, they are either falling in real terms, or at least falling relative to the population’s capacity to pay. The picture is mixed and defies easy generalizations, but at a first approximation it is probable to say that a considerable proportion of the money that has gone into universities in the Global South since 2018 has gone not to increase spaces, not to improve quality, but rather to lower required student contributions.

Figure 2: Average fees at public universities as a percentage of gross domestic product, Global South, 2006 and 2018

It would be understandable, of course, if money was spent this way in the late 00s when public funding to higher education was jumping at record rates (over 10% per year) across the Global South. But the amazing thing is that it continued after the cash flow was turned off in the early 10s and then fell to a rate of just about 2% per year. More private money in higher education – either through tuition in public institutions or in privately-funded institutions – could have made a real difference in terms of quality. But following the Arab Spring, few governments in the Global South have wanted to offend students, who can be still be volatile political actors. Result: higher education institutions are asked to make dollars go further and further, accepting more and more students on the same budget.

Eventually, something is going to have to break. Either institutions will need to stop accepting students, or educational/research conditions will deteriorate to the point where academics begin to exit the profession or leave to richer countries.

The issue of mobilizing non-public funds to support universities is going to return to the agenda eventually: universities in the Global South will suffer needlessly if these funds remain inaccessible. For international agencies interested in helping them take theses steps, understanding why all these governments ignored this advice for the last 20 years seems like an important task before pushing the same solutions one more time, even if those suggestions are correct.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post