In tuition policy circles, there are a lot of “grass is greener” perspectives: that is, people arguing about affordability based on foreign examples of either high or low tuition. But one of the problems with looking at “affordability” of higher education in cross-national contexts is that affordability is a matter of perspective. What’s affordable in one country often isn’t in another. I don’t mean this simply in the trivial sense that some countries are richer than others. Obviously a $3,000 tuition fee is more affordable in Canada than it is in Zimbabwe. Rather, I mean it in the sense that students and families in different countries with similar standards of living have different views about what kinds of sacrifices they are prepared to make in order to send their kids to school.

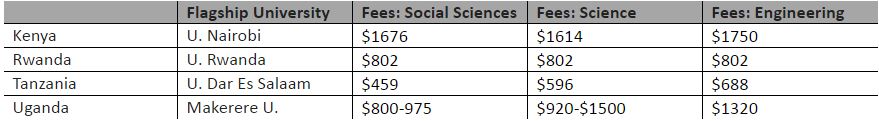

So here’s one example: East Africa. There, you have four countries with fairly similar higher education systems. Each has one obvious “flagship” institution, and a mix of private and public institutions. The private sector teaches about a third of all students in Tanzania, and about half in Uganda and Rwanda; in Kenya, the figure is between 10 and 15%. I can’t show you average fees in each country because they don’t exist, but here’s a selection of fees at each country’s flagship institution, in USD, at current exchange rates, which gives you a rough idea of the relative fee levels across the region.

Table 1: Tuition Fees at East African Flagship Universities, 2015-16, in USD

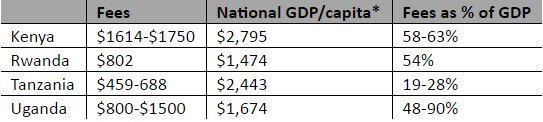

Now, let’s express those fees in terms of GDP/capita to get a sense of how “affordable” these fees are. For comparison, tuition + compulsory fees in Canada are about 13% of GDP/capita.

Table 2: Tuition Fees at East African Flagship Universities, 2015-16, in USD (*Source: World Bank 2013)

Finally, let’s talk about availability of student assistance. All four countries have student loan programs. Uganda’s is very small – only a couple of thousand loans per year, starting in 2015 – while Tanzania’s is the largest, serving somewhere between a quarter and a third of all students. The other two countries are in between, though Kenya’s system more resembles Tanzania’s, and Rwanda’s is closer to Uganda.

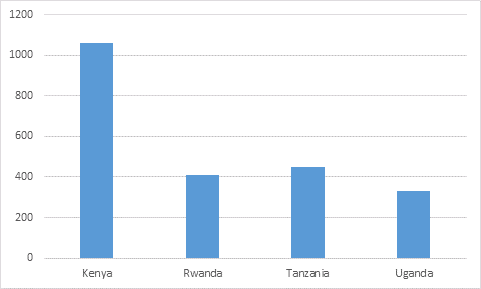

Now, based on all that, what do you think access rates look like? Most people would probably put Tanzania (cheapest, best student aid) at the top, and Uganda (expensive, least available student aid) at the bottom. But here’s what enrolment rates actually look like:

Figure 1: University Students per 100,000 of Population, East Africa, 2015 or Latest

A couple of caveats about the data. Tanzania’s numbers are different from the others because nearly a quarter of its student body is enrolled at the country’s Open University, many of them in education programs. Uganda’s numbers are somewhat lower because compared to the other countries, it has more tertiary students in non-university institutions. But that aside, the real story is that Tanzania (richer, cheap tuition, better loan availability) is a lot closer to Uganda (poorer, more expensive, almost no loans) than it is to Kenya in terms of access rates. And if you spend any time in the area, you’ll quickly learn something else: universities in Tanzania are far more likely than those elsewhere in the region to say they can’t expand without loans; the claim is that students simply won’t come if fees rise or loans aren’t expanded because “students can’t afford it”. But on the face of it, that’s nonsense, as the costs for students elsewhere in the region are manifestly higher, and they are not thought to pose quite so severe a barrier.

The difference is entirely cultural, and has to do with collective saving mechanisms. In Uganda, it is normal for a family to hit up their neighbours and co-workers for a few dollars each semester to help their kid get through school, which everyone does because they know that when it’s their turn to put a kid through school, the donation will be reciprocated. In Tanzania, people will do the same to cover the cost of weddings or sometimes hospital fees, but not for tertiary education. Locally, most people attribute this difference to the after-effects of the long period of socialism under President Julius Nyerere. This view says that Tanzanians simply got used to government paying for everything, and citizens haven’t entirely adapted their thinking to the post-1990s reality.

I have no idea whether or not this is true, but it does beg some interesting policy questions: What’s the right policy to follow if a population has sub-optimal savings and investment habits? Is there any practical way to nudge a country from a Tanzania-ish state to a Ugandan one? If not, are you stuck with permanently high tertiary education subsidies because households can’t be depended upon to contribute?

These are some serious questions, which have real implications here in Canada, too. After all, wouldn’t Quebec universities be better off if Quebecers were a little more Ugandan and a little less Tanzanian?

Something to ponder, anyway.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post