A lot of people have been speculating about what’s going to happen in the Ontario College sector now that its use of the money-printing machine of ever-increasing international student numbers has been shut off. Some have speculated about Laurentian-style bankruptcies. I think that’s extraordinarily unlikely given the way this is playing out. I do think some significant changes—sometimes quite deleterious ones—are going to occur in Ontario post-secondary. It’s just that it’s going to happen at the level of individual programs, not institutions.

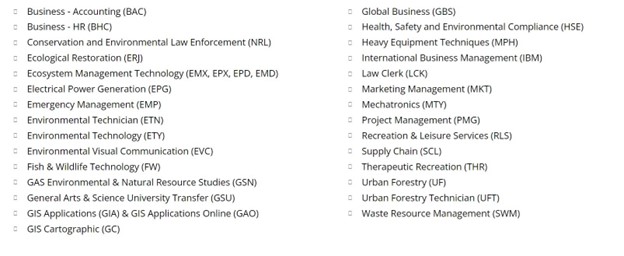

Let’s take an example here. A couple of weeks ago, Sir Sandford Fleming College announced a comprehensive set of program suspensions; that is, they are not taking any more students, but students currently in the program will be taught to completion. To my knowledge Fleming is so far the only college to make such a comprehensive statement (apologies to anyone else I might have missed). Here are the suspended programs, from the college’s website:

Now, you can imagine how the community reacted. “But there is such a societal/economic need for X/Y/Z. How can the college cut these programs?” Now the college did not, unfortunately, issue a detailed memo outlining the reasons for the cuts, but if they are like every other college I know, they did a pretty rough and ready calculation of which programs were the least economical to run, and cut them. These specific programs simply put were the ones that required too much in terms of cross-subsidies from other programs. They couldn’t bring in enough money from sources both private and public to cover costs, so they were chopped.

There are of course two ways to trigger a program closure decision. The first is if student numbers in that program fall below the level where a program can feasibly be run. That number varies a bit by the unit cost of the program and the extent of the tuition and subsidies in each program (different provinces have different formulas with respect to funding, and the tuition income depends quite a bit on whether the students in the program are of domestic or international origin), but there aren’t many programs out there that can be run at cost with less than 30 students. So one way that the loss of international students Is playing into the program apocalypse is simply that domestic demand for some of these programs is on its own insufficient to sustain them: they need international students in order to make sense economically.

Pointing this out is often extremely inconvenient because it clarifies the fact that many the programs that people are most incensed about losing are ones often don’t have high enrolment. So, for instance, if you dislike the decision to cut various environmental programs (because aren’t we in an environmental crisis?), it’s harder to criticize the decision if that program isn’t actually attracting many students.

(You can look up enrolments by program up to 2021-22 here; more recent data should have been posted by the Ministry by now but the rat-bastards simply refuse to publish more up-to-date data. It’s incredibly irritating. It’s interesting to note, though, that Fleming had a *lot* of program areas with enrolments hovering near the break-even point.)

But of course, there is another way that the loss of international students can cut into programs and that is by reducing funds available for cross-subsidization. Sometimes, for a variety of reasons, institutions run programs at a loss. This is especially true in the trades, which are incredibly expensive to run because of costs in acquiring and maintaining equipment, but are seen as a core mission by many colleges. So, for instance, there probably weren’t that many international students in the Heavy Equipment Techniques program, but the surpluses that international students are generating in other programs like business are likely what has kept the program alive for many reasons.

It should also be said that not all program closures are equal. Sometimes, a college has many programs which are very similar and people who are unable to access one can still switch into an adjacent program fairly easily. So, for instance, Fleming’s “Fish and Wildlife Technology” program might be closed, but it still has a “Fish and Wildlife Technician” program which has very healthy enrolments. So in part what the Program Apocalypse will achieve is a probably overdue process of program streamlining.

Now, you might say, “What about the public interest? Shouldn’t that play a role in decisions about program closure?” And the answer is: yes—up to a point. That’s what the public subsidy is for. The problem is, in Ontario at any rate, that the subsidy per-student is tiny: barely $6,500 per student. It is simply not big enough to make a difference, especially where high-cost programs are concerned.

And this is the real nub of the Program Apocalypse: Ontario is perhaps a special case, but right across Canada, provincial governments have been underfunding colleges for a very long time. International students provided the system with the financial slack to continue business as usual. Absent that, what we are going to see is colleges making the hard business decisions needed to keep themselves afloat. International students let colleges do “more with less” from government. We’re about to see what “less with less” looks like. It will be interesting to see how governments react.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

The other issue that needs to be considered when cutting programs is that it will remove SOME of the cost but ALL of the revenue. Overhead is a large component (over 50% in most models we’ve built) and removing programs with minimal to no reduction of overhead will simply redistribute this over fewer programs, which could lead to a worse financial position overall. Having a detailed view of which programs may be covering all of their direct cost and some overhead vs those not even covering direct cost will provide a better way of determining which programs could be cut (also noting your point about loss making core programs). The other big thing that is subsidized by academic programs is research, there is certainly lots of cross-subsidizing between schools and programs, but a lot goes to supporting internal research as well.

It is interesting to go to the College website and compare this to the many programs that are not closed.

I can see a lot of programs in the list above that politicians like to promote as being essential for employment pipelines and “real-world needs”, while on the other hand, I can see a lot of continuing programs that seem to flourish and that politicians would not promote in the same way. If technical trades programs are so essential for the economy, why is neither the provincial government nor local industry stepping up to save them? Ceramics seems to trump mechatronics. Do politicians sometimes suffer from tunnel vision and not recognize what people really care about?

If you check your stats- the heavy equipment techniques program at Fleming actually runs very efficiently. The equipment used is bought and paid for and because they are training technicians, there is very few hours put on this equipment so maintenance is all done as part of the curriculum. The issue with this program is that there are high faculty costs due to it being an accelerated delivery- but that has not been publicly stated to my knowledge. Programs like the heavy equipment operators program are the ones with high equipment maintenance As far as the government enrolment stats- they are inaccurate.Since covid- this program has run at about 80% capacity.

“Pointing this out is often extremely inconvenient because it clarifies the fact that many the programs that people are most incensed about losing are ones often don’t have high enrolment. So, for instance, if you dislike the decision to cut various environmental programs (because aren’t we in an environmental crisis?), it’s harder to criticize the decision if that program isn’t actually attracting many students.”

This would seem to make program cancellation a more-or-less arithmetical exercise of accountacy. On the other hand, a couple of paragraphs later, you note that “Sometimes, for a variety of reasons, institutions run programs at a loss. This is especially true in the trades, which are incredibly expensive to run because of costs in acquiring and maintaining equipment, but are seen as a core mission by many colleges.” Which makes program closures something different entirely, a statement of core mission, of belief, of purpose.

What I object to is the bad faith of many institutions which say that certain programs must be cut because they can’t run at a profit — i.e., it’s just accounting — while shamelessly spending more than is absolutely necessary on something else. What one chooses not to spend money on is always a matter of values, and never just a matter of accounting.