Today let’s talk about four countries in Asia: Japan, South Korea, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan.

Japan, the first Asian country to modernize, went through a thoroughly transformative economic miracle in the 1950s and 1960s. It currently has a population of 125 million, 10th largest in the world. South Korea was the next of the so-called “Asian Tigers” to follow, achieving “developed-country” status in the 1980s and 1990s. It currently has a population of 51 million. Though both have been to some extent eclipsed on the scientific front by the ascendance of China, these two countries came to be the parts of Asia that are closest to North America and Europe in terms of their higher education systems. Not only do they have hundreds of universities, but a good number of them are among the best in the world, including Todai and the other “imperial” universities in Japan, and Korea’s SKY (Seoul-Korea-Yonsei) universities.

Uzbekistan (34 million people) and Kazakhstan (19 million people) are a bit different. They are ex-Soviet republics. Both are poorer than Japan/Korea; Uzbekistan more so than Kazakhstan, which is more or less on par with bits of southern Europe like Bulgaria. But both are growing quickly, not least based on their natural resources, and Uzbekistan’s recent economic liberalization measures are the envy of the region. As far as higher education goes, their systems remain underdeveloped. Both inherited a research university as part of their Soviet inheritance (Al-Farabi Kazakh University in Kazakhstan and the National University of Uzbekistan). In addition, Kazakhstan has tried to jump-start higher education in the country by creating a massive, prestige university centre known as Nazarbayev University (it’s sort of like King Abdullah University of Science and technology in Jeddah, only with not quite so eye-watering an endowment). But participation rates in post-secondary education were until quite recently fairly low, so these systems appear—to western eyes at least—somewhat small.

(The other largely unknown factor is that both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan resemble nowhere on earth so much as the Canadian prairies. You would be hard-pressed to find two countries more similar to Western Canada climatically. The area between Samarkand and Tashkent definitely looks like Alberta’s foothills, if someone ever decided to try growing cotton there).

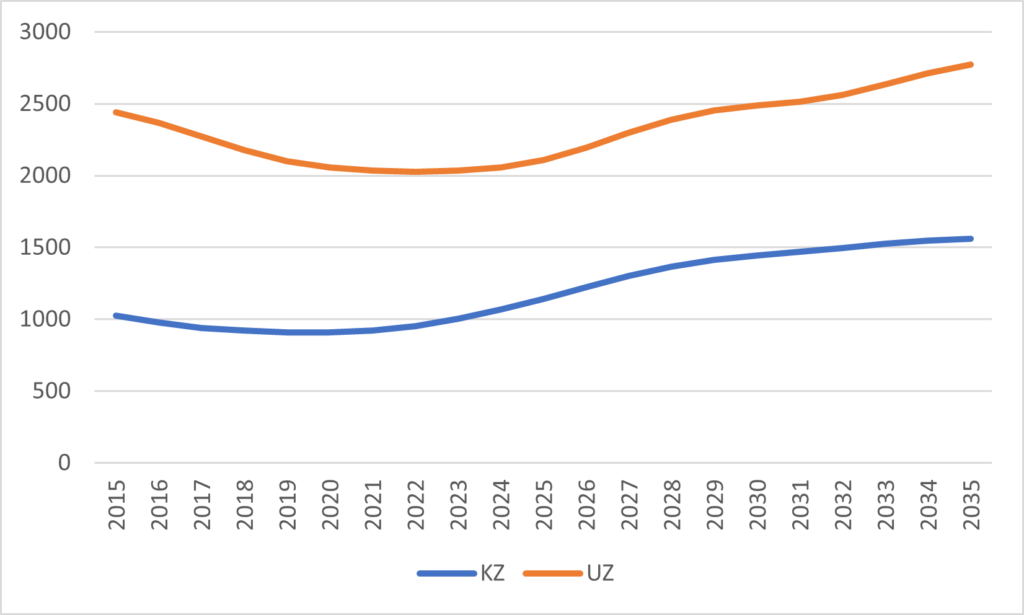

Now that we’re all caught up, take a look at this graph.

Figure 1: Actual and Projected populations of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, aged 18-21, in thousands, 2015 to 2035

Like the rest of ex-Soviet space, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan saw their birth-rates plummet in the 1990s after the dissolution of the Union and the economic chaos that followed. That created a serious fall in enrolments throughout the 2010s. But to a greater degree than Russia and other countries in the region, birth rates recovered quite strongly after 2000. And as Figure 1 shows, that’s leading to some enormous growth in post-secondary aged population. From 2020 to 2035, Uzbekistan expects a 35% increase in youth numbers: in Kazakhstan it’s a jaw-dropping 72%. And this actually underplays the challenge, because both countries have seen substantial jumps in secondary completion rates over the last decade, meaning the jump in qualified 18-21 year-olds is up by much more than these figures.

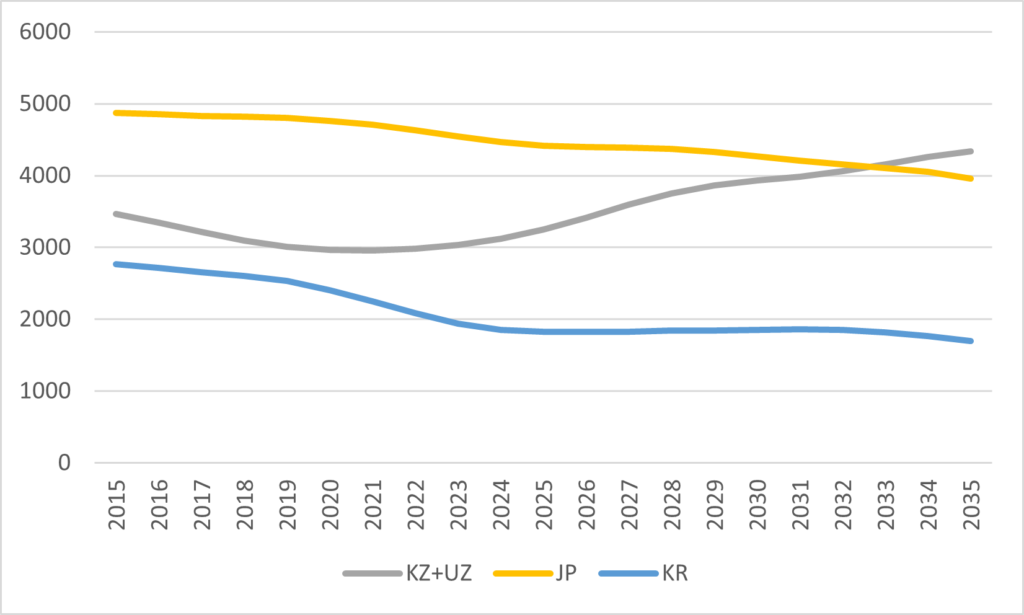

Now let me show you how this compares to what’s going on in Korea and Japan.

Figure 2: Actual and Projected Populations of Japan & Korean vs Kazakhstan/Uzbekistan, aged 18-21, in thousands, 2015 to 2035

Got that? Although in 2020 there was not a huge gap between the 18-21 population of Korea and that of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (which you’d expect since they are roughly the same size), by 2035, growth in the Central Asian countries and decline in Korea will mean that K+U will have a youth population more than twice as large. And Japan, which currently has a total population about 150% larger than our two central Asian countries, will fall behind K+U for 18-21 year-olds somewhere around 2033.

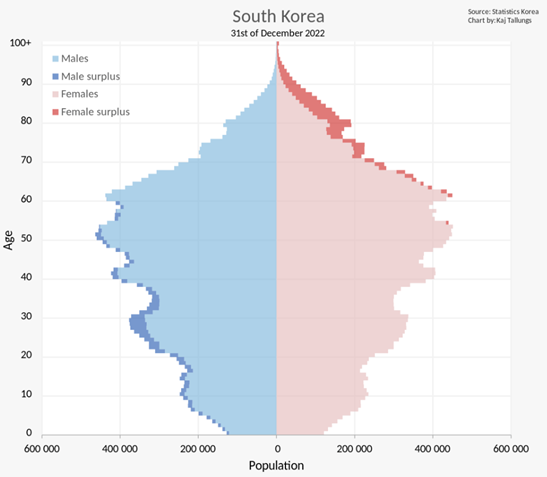

This is, of course, as much a story of demographic collapse in East Asia as it is of growth in central Asia. If you really want to see something terrifying, check out the population pyramid of South Korea, which makes clear that the real collapse in university enrolments really are going to fall off a cliff after about 2033.

Figure 3: Population Pyramid for South Korea

In any event: there is lots of opportunity here for institutions paying attention and who are in it for the long haul. Yes, obviously, these are countries where Canadian institutions should be doing more to attract students. But there are also a lot of opportunities in-country as well. Both countries are dying for foreign institutions to set up campuses there, either as standalone operations (Politecnico di Torino set up shop in Tashkent quite awhile ago), or as campuses within campuses (this Astana Times article suggests that the University of Calgary was poised to do this with Shakarim State, but I can’t find any indication of this on the U of C website, so I am not sure what is going on).

Would lack of talented students be a challenge? Probably, yes, if Kazakh and Uzbek PISA scores are anything to go by. But we know how to deal with that: just repeat the Canadian strategy in China and set up Canadian curriculum high schools (again, I am pretty sure these would have good take-up). And setting up campuses—or even just extended research partnerships—with institutions in this part of the world would get Canada in on the ground floor of working with higher education countries which are looking to start pumping money both into both post-secondary expansion and research.

Adventurous universities in Canada—particularly those that specialise in agriculture, hydrology, mining, and the like, where Uzbek and Kazakh universities also have relevant strengths—could do quite well in the region if combined with a multi-faceted approach to partnership and recruitment. And also if they have the required patience: this would necessarily be a multi-decade project.

Canada missed out on the benefits being among the first movers into places like India or South-East Asia: we need not suffer the same fate in Central Asia. That is, if we’re actually alert to the opportunities.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post