If there’s one drum Canadian universities love to beat on international education, it’s that Canada is falling way behind other countries in terms of students gaining international experience during their studies. It’s a great story, except for one tiny thing: it’s not true. It’s really not true.

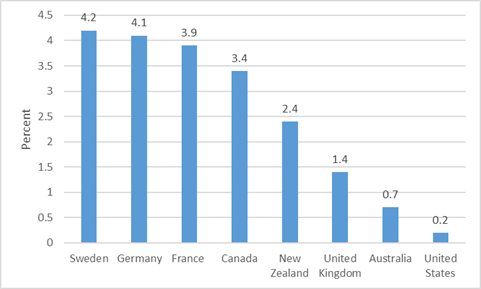

Check out, for instance, this data below, from the most recent OECD Education at a Glance, which shows the percentage of total students from each country who are enrolled abroad (Data is from Table C4.3, for those who want to a little bit of extra nerding out). What we see is that Canada’s rate of studying abroad is actually not that far from the major countries of Europe, ahead of the UK, four times higher than Australia and indeed highest of any non-Erasmus country in the OECD.

Figure 1: Percentage of National Students Enrolled Abroad, select OECD Countries 2015

Now how can that be? Doesn’t everyone know that – as Universities Canada never tires of saying – Australia has five times as many students studying abroad as Canada? Well, no, for two reasons.

The first reason is that whenever Canadian universities talk about the benefits of studying abroad, they don’t actually mean doing one’s studies abroad – what they actually mean is people studying in Canada and taking short study excursions outside the country. But there are actually a whole heck of a lot of Canadians who actually do their entire studies abroad. We’ve got over 20,000 Canadians studying in the United States – mostly graduate students – and there’s another 10,000 or more spread around the rest of the world. And proportionately, that’s way more than other non-EU, non-Erasmus country.

Now, one response to this is “that’s not really study abroad”, and the studying abroad that matters is the short-term kind. But I think at that point we would have to ask ourselves – why get worked up over short-term mobility and not count longer-term mobility? What’s so special about short-term mobility? (I think there are some reasonable answers to that question, but we need to get beyond handwaving on this).

The second issue has to do with what appears to be widespread misunderstanding of how different countries count students going abroad. Take the famous figure of 15% of Australian students who study abroad, a number (a figure which is actually a couple of years old – the figure is now 19%)., which is often compared to Canada’s (alleged) 3%. As I pointed out back here: this is an apples and oranges comparison because the Australian figure counts graduates who claim a study abroad experience and the Canadian one is the percentage in total undergraduates who have a university-sponsored study abroad experience in any given year.

These two methods can give you wildly differing results. In fact, in the United States, the annual “fast facts” which accompany the annual “Open Doors Report” (see bottom right of page 2) shows exactly how different those numbers can be. Using the Canadian method of counting, the percentage of US students studying abroad is 1.6%; using the Australian method, it is 15% (this is a slightly exaggerated effect because the 1.6% includes both students 4-year and 2-years while the 15% includes only 4-years – a more apples-to-apples comparison involving what we would call “university students” only would probably be something like 3% and 15%).

But in fact, we don’t need US examples to show that the two methods given completely different numbers. If turns out that the Australian survey which gets us that 15% (or 19% or whatever) figure also provides annual study-abroad figures. And guess what? Turns out the number of Australian students going on short-term abroad in any given year is about 40,000. Since Australia has about 1.3 million students, that puts their annual study-abroad numbers at around 3% – or exactly where Canada’s numbers are according to Universities Canada.

So, are Canada’s study abroad numbers the equal of European countries? No. But that’s to be expected because of geography. What we do have, however, is a rate of study abroad that is equal to or better than any country outside the EU. And far from us needing to “catch up” with Australia, it’s more likely them having to catch up with us.

Could we do more than we currently do? Could we use more funds to make study abroad more inclusive? Yes and yes. But let’s drop the whole “we’re falling behind” narrative. It’s demonstrably not true and continuing to use it does the credibility of those pushing for better internationalization no favours.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I am always shocked by how few Canadian students know about the cheap/free semester (or more) at partner universities.

Granted, the choices are uninspiring third-rank universities (no Harvard, Oxford etc. and other well-known for being well-known), and the costs of living abroad is more a burden to local students than they are currently paying.

Still it should be the second thing in their enrollment packages, with reminders every 2 years to take advantage of it.

But then the universities have dropped foreign language requirements from graduation, so they don’t really care. And they don’t promote the value of the location of the second- and third-rate universities they have been granted partnerships with.