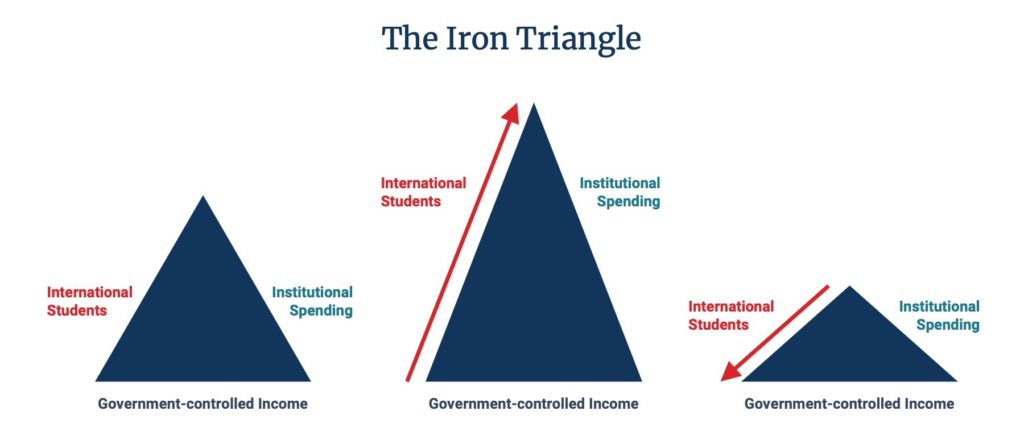

Though there are ups and downs and local variations, over the past decade, three factors characterize the finances of the Canadian higher education sector.

- Governments are refusing to increase transfers or tuition by more than inflation.

- Institutions are continuing to grow faster by 2% than inflation because saving money and enforcing priorities is hard.

- The difference is being made up by income from international students.

That’s it, that’s the whole story. It’s a classic triangle: if one side increases in length and another one does not move, the entirety of the accommodation lies on the third side of the triangle.

Now, to be fair, at the system-level this dynamic seems to work. On average, the system is chugging along reasonably, with foreign student income covering the difference between eroding government public funding and the steady growth of institutional spending pretty much exactly. But the system is made up of both above and below average individual parts. Laurentian, for instance, was below average on the international student front, and that was a major factor that put the institution at risk given the lack of either spending restraint or extra provincial funding.

For the moment, there don’t seem to be any other Laurentians out there. But there are a bunch of institutions out there who seem to be in moderate trouble stemming from challenges in international recruitment and who are therefore having to shift the other (expenditure) edge of the triangle. Three examples are the University of Regina, the University of Victoria and the University of Guelph.

University of Regina’s problems – outlined with commendable candour here – are arguably pretty containable. The institution had about a $3 million structural deficit heading into this year – largely due to a pandemic drop-off in international enrolments. It had banked on getting that money back through enrolment increases in 2022-23 but instead saw more falls, in some cases quite drastic ones. Domestic enrolment for spring/summer last year was down 15% and for fall about 4%. International enrolment is up, but by less than projected. Put all that together, and you’re looking at a structural deficit of nearly $13 million, or around 4% of income. Add in expected salary lift for 2023-24 you get close to $22 million, or 7% of income. That’s a big number, particularly when something close to half of your expenditures are effectively uncuttable due to tenure.

Regina’s response to this is basically half-revenue increases, half-cuts. They already boosted international recruitment for the winter term (netting $3m or so), and plan to see increases of 15% for next year and 10% each of the following years. Meanwhile, they are looking at cuts in expenditure totalling about $16 million over three years – basically equivalent to about 2/3 of expected raises over that period. This year’s budget presentation is here, if you want the details. It’s a pretty sober approach but i) even this only gets them back to balance, it doesn’t cover losses over the past few years and ii) the strategy quite clearly relies on international students without offsetting housing supply, meaning this budget plan is predicated on raising rents in the City of Regina and iii) goodness help them if they miss those recruiting targets.

The University of Victoria has a similar story but without the ability to do long-term planning. The university ran a $17 million deficit in 2022-23, again, mainly due to the fall-off in international students during COVID. That was permitted under COVID, but as a rule the province of British Columbia does not allow universities to run deficits, so now that COVID is over, UVic has to get back to balance promptly. Unlike Regina, its plan back to balance does not depend on large increases in international students or indeed much on increased income. Instead, it is looking at about an $11 million expenditure cut next year – a bit more than 2% of the budget – most of which is going to come through a hiring freeze. You can see a full accounting of the University of Victoria’s approach here.

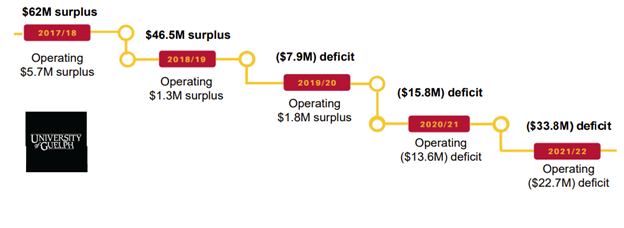

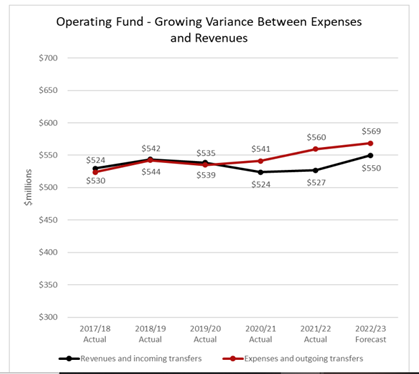

Then there is Guelph. Guelph’s story isn’t just one of COVID-era misfortune: there’s also the 10% cut to domestic tuition imposed by the Ford Government, which cost the institution something in the region of $25 million. It’s also a story of an inability to control costs in the face of these revenue problems. As a result, and as shown in the graphics below from a recent Guelph Senate document, what you see is a turn-around over five years of nearly $100 million, from a $62 million surplus to a $34 million deficit.

The initial Guelph response, for some reason, was to increase domestic enrolments (see here for my previous comments on this), a strategy which can only be described as “low-return”, since the government has capped institutional grants through its corridor model. Now, it has gone much bigger, considering whether to hand over a significant amount of their international student recruitment to Navitas (presumably with guarantees of fairly large increases in international student numbers). Though it may simply reflect the paucity of public data sources (or at least what the administration feels like sharing with the public), the recovery plan seems to be much vaguer: there is talk about “transformation”, and a culling of programs with ether low enrolment or falling enrolments/applications. Already the institution has announced plans to cut 16 programs and also announced a class-size minimum of 15 students (with exceptions possible on a case-by-case basis). The former measure seems unlikely to drive major savings (cutting programs only really cuts costs if you can also cut staff, which isn’t happening); the latter at least cuts costs to the extent you can reduce the use of sessionals and reduce future hiring needs. Time will tell whether any of this will work; at a minimum, the Guelph approach seems to have engendered a good deal more opposition from faculty than equivalent efforts at Victoria and Regina.

Let me emphasize this: these are not one-offs. In any given year, some institutions are going to have a rough go with recruitment. One rough year in recruitment equals four years of lowered revenue as each cohort takes that long to move through the pipeline. Two bad years within a span of four? That’s real trouble.

Now you can look at all these simply as “natural corrections” implied by the triangles above: when the international student side shrinks, and the government-controlled funding stays pretty much the same, the spending side must adjust. That’s not necessarily fun for anyone involved, but it is evidence of the system working more or less as intended (even if no one at any level of government has the guts to actually explain things this way).

One of these days, though, one such crisis is going to spiral out of control and there will be another Laurentian. And fingers will no doubt be pointed at institutional administrators, saying they weren’t fast enough to cut, or to add international students. But remember that this, too, is the system working as it is intended to work. Encouraging institutions to find market solutions to bridge the gap between what they want to spend and what governments are prepared to give them, while refusing to give them a safety net, was always a strategy that had the potential to create catastrophic outcomes.

*Corrections: a previous version of the blog indicated that the University of Guelph had already commissioned Navitas, but the institution is still considering whether to commission the firm. Also, for the University of Victoria, we have learned that while there were significant expenditure reductions, they were in reaction to an in-year deficit rather than an end-of year deficit (that is, the university’s expenditure reductions were preventative rather than reactive).

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

In fact, in Ontario at least, provincial government transfers and domestic tuition have fallen well behind inflation for several years.

The government cut domestic tuition by 10% in 2019-2020, and it has been frozen ever since. The cut was not compensated by new transfers. In fact, the provincial government also froze its own per-student transfers with the result that provincial funding now makes up less than 30% of total funding at many universities.

There are also limits to how much you can charge international students to cross-subsidize domestic students (currently about $50k per year at some Ontario universities): I doubt Ontario universities will always benefit from a bottomless well of wealthy international students.

Could this “special” Ontario situation partly explain the problems at Guelph? It seems that if funding and domestic tuition both remain frozen eventually neither international students (more paying more) and cuts won’t be enough to balance the budget.

In any case, sufficiently deep cuts could eventually make the university less attractive to international students, leading to a death spiral!

Laurentian is very special in that the funding shortage there was largely due to an insanely reckless building frenzy. The pandemic only brought this to the fore. So I don’t think that the situations at Guelph, UVic and UofR compare to that. With respect to those three universities, their situations in conjunction with provincial budget situations beg the question: Do governments in Ontario, BC and Saskatchewan aim for a consolidations of universities? This would be particularly delicate for BC and Saskatchewan, where provincial capitals are affected. Of course, this would presume some form of planning, albeit evil. However, I don’t think that there is any planning of any kind involved, except for the desire to not spend money on portfolios where provincial leaders feel that being cheap comes easy. Nonetheless, costs must be cut, and the sacred cow that should take the fall are merit increases. Outstanding special performance should be rewarded through one-time bonus payments, but we all know for many years now that the merit increase system is unsustainable.