One thing everybody hates is red tape – especially pointless reporting requirements which take up time, money and deliver little to no value. Of late, Canadian universities have been talking more and more about various types of reporting burden and how they’d really like being freed from some of it. For those interested in this subject, it’s instructive to see how the issue has been handled in Australia.

The peak university body in Australia (called – appropriately – Universities Australia) began the drumbeat on this issue about six years ago. They commissioned an independent third party (self-interested note to university associations: 3rd party investigations give your policy positions credibility!) to provide an authoritative report on Universities’ reporting requirements. The report went into exhaustive detail in terms of how much staff time and IT resources institutions devote to each of 18 separate data reports required by the commonwealth government. What they found was that the median Australian institution was spending 2,000 days of staff time and $800-900,000 per year on these reports, roughly a third of which went on collecting data on research publications.

Now, that may not sound like much. But that’s only data going to the federal ministry responsible for higher education. It did not include reporting costs related to quality assurance bodies and submissions to the national higher education regulator(s). It did not include the costs of research assessment exercises (and certainly didn’t count the cost of applying to various funding agencies for money, which is a whole other nightmare story in and of itself). It did not count regulation related to state governments (Australia is a federation but in contrast to Canada, higher education is mostly but not exclusively a federal responsibility), or anything relating to its required reporting to the charities commission, reporting on government compacts (similar to Ontario’s MYAs), health agencies, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, professional registration bodies….the list goes on.

The point here is not that institutions should be free of reporting requirements. If we want transparency and good system stewardship, we need institutions to be providing a lot of data – in many cases much more data than they currently provide. The point is that nobody is co-ordinating those data requests and making any effort to reduce overlap. If you’re getting data/reporting requests from a dozen or more different bodies, it would be useful if those bodies spoke to each other once in awhile. Also, as a general principle, or keep regulatory requests to what is absolutely needed rather than what regulators might just like to know (appallingly, the Government of Ontario last year attached a rider to a childcare bill gave itself the right to take any piece of data held by an Ontario university or college, including physical and mental health records, something which in my line of work is known as “as far away from good practice as humanly possible”).

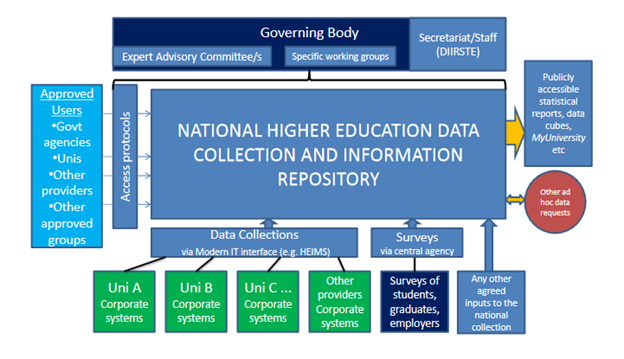

There were, I think, two key suggestions which came out of this exercise. One was that they government should be required to post a comprehensive annual list and timetable of institutional reporting. This was less for the universities’ benefit than the government’s: it helps to be actively reminded about other people’s reporting burdens. The second was a very sensible suggestion about how a streamlining of requirements could be handled by the creation of a national central data repository. The design of this system is shown in the figure below.

This is similar in spirit to the way North American universities have created “common data sets” in reaction to requests for information from rankers and guide-book makers; where it differs is that it brings data customers into the heart of the data collection process, and it explicitly requires them to put data out into statistical reports for public consumption. In other words, part of the quid pro quo for more streamlined reporting is more transparent reporting. Which is a lesson I think Canadian institutions should take to heart.

The results of this were mixed. The government held its own hearings on regulation which led to significant cuts to the main higher education regulator, TEQSA, which left the university somewhat relieved (they got a much lighter-touch regulator as a result) and somewhat horrified (while they liked a light touch for themselves, they were panicked at the prospect of light touch regulation for the country’s many private providers). As for the report commissioned by Universities Australia, while the Government responded to the review in a very positive manner very little in terms of concrete change seems to have happened.

Still, these reports change the tone of the discussion around higher education at least for a time. It would be useful to try something similar here – especially in Ontario.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post