Very few things in higher education drive me quite as spare as the focus on “affordability” in higher education.

First of all, no one defines it properly. When most people talk about affordability, they are using it as a synonym for price. But this is nonsense because affordability is a ratio: price divided by ability to pay. What is affordable for someone in Westmount or Tuxedo or North Van is quite different from what is affordable to someone from Verdun or the North End or the downtown East Side.

Second of all, there is a tendency to equate affordability with accessibility. If you define affordability strictly (that is, as a ratio), then affordability is a necessary but insufficient condition for accessibility (for instance, Sweden has free tuition but has been having increasing access problems because of the excess of demand over supply for places). If, on the other hand, you define it as a price you get something that even the briefest glance at international experiences on access would reveal as total nonsense (low/zero fee countries do not have fewer access issues, they just have different ones).

But, you know, this is the modern way of things. Despite an unprecedented era of low price-inflation, despite both average and per-capita median income having risen steadily and fairly substantially since the mid-1990s, somehow, affordability – not just of tuition but everything – has become a major political issue.

Exhibit One is this recent work done by the research and strategy firm Abacus, and a related presentation the company gave to the Broadbent Foundation. It is – frankly – one of the most horrifying things I have ever read.

Let me just give you a couple of snapshots of what Abacus found:

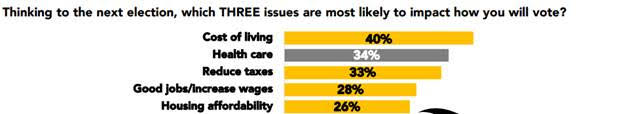

Here’s the first finding of note: that “costs” are the most important issue. This is “costs” distinct from housing (which is an issue, at least in Toronto and Vancouver). What costs? No idea. Just costs. According to the electorate, costs are bad.

According to this next chart, 90% of people say the costs of things they need in their life are rising. This is at one level true. Of course, anyone who is paying attention to facts will know that both average and median incomes are rising faster than prices and have been pretty continuously for two decades now.

But facts? Who cares about facts? Apparently 71% of Canadians think their taxes are going up. And while their have been some tax increases in the past decade in a couple of provinces, and nationally for the top 10% of taxpayers or so, the only way we can get to 71% is if we include people whose taxes are going up because their incomes are going up. Which is just nonsense.

And here are Canadians’ views on how to make life more affordable for Canadians. By a nearly 2-1 margin, Canadians believe the answer is to lower costs, not to raise wages.

It is all kind of terrifying. Apparently the Canadian electorate no longer believes – if it ever did – that growth leads to prosperity. Rather, it is suppressing the price mechanism that leads to prosperity. Conservatives campaigning on cheaper beer and (eventually) cheaper tuition are apparently on to something, politically at least. Economically, it’s illiterate and half-way to Caracas, but there we are.

The upshot of this is incredibly damaging for higher education politically. There is no world in which the economic benefits of higher education are better described by “lowering prices” than by “raising wages”. The higher-education-is-good-for-the-economy argument is entirely about accelerating economic growth, productivity and wages. If that is not, in the final analysis, how Canadians think prosperity is to be achieved, then the sector’s entire case for public support is fatally undermined.

Now, perhaps one shouldn’t panic too much over this. It’s hard to say how much of this is real, and how much of it is shaped by the wording of the questions and the survey instrument. It would be interesting to see other firms attack these questions in a slightly different way to see if the results hold. We also shouldn’t get sucked into thinking that these views are a new phenomenon; Abacus implies this is the case, but as far as I can tell there this is the first time many of these questions have been asked and so there is no time series to check. Maybe Canadians have always been this economically deluded. But still, this urgently requires attention. If Canadians genuinely think price controls are the way to prosperity, higher education is in deep, deep trouble politically. A greater focus on growth, why it is good and how institutions contribute to it, is clearly in order.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I like this post, though by comparing the Broadbent survey with arguments about affordability of education it does mix apples and oranges a bit. Still, the argument you make about affordability is well-taken, and the Broadbent survey offers a nice illustration. And all this is my my own focus is on access to education, not affordability, and indeed, I think a lot of the talk about affordability is a dodge to avoid talking about access.

I also take your point about the economic argument for education as being about growth, not savings. But the two are not mutually exclusive – if, for example, you lower the cost of building a house, more people may build a house, thus creating overall growth. The argument for reducing the cost of an education is the same.

But we are agreed, I think, that we cannot cut our way to prosperity. You need investment to create growth, and the argument really centres around questoons concerning who should make that investment, and what sort of investments create the greatest benefit.

Gosh, cost, affordability, accessibility, sounds like prelude to elections. Capitalizing and economic fear bs isn’t new, of course we’ll go broke if we vote left, lose all social supports if vote right, and will be just right if we stay in the middle. The good part is education is rarely on the of voters minds unless they’re school age or work in the sector.