A couple of weeks ago, Statistics Canada published a study that looked at overqualification among university graduates (available here). It’s a good-news story that deserves a bit more attention than it’s received.

The study uses data from the 1991 and 2006 censuses, as well as the 2011 National Household Survey, to look at the changing occupational profile of Canadians aged 25-34. To digress briefly into the world of occupation statistics: every occupation in North America is given what’s called a NOC (National Occupation Classification) Code. Each NOC code has a set of employment characteristics next to it. A job classified as “A” requires university, “B” requires college, “C” requires high school, and “D” requires “on the job training”. There is a separate category for managers, who are deemed not to have an educational requirement (sounds silly, until you realise that business owners – even those from corner shops – get classified this way). In most overqualification studies (including this one) if you have a university degree, and you’re in an occupation listed as B, C or D, you’re considered “overqualified”.

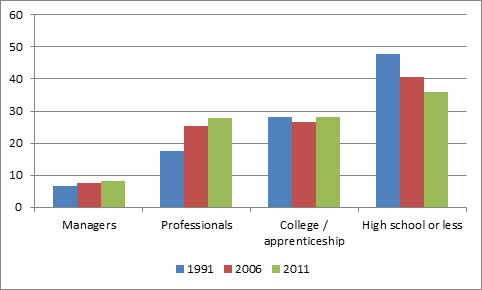

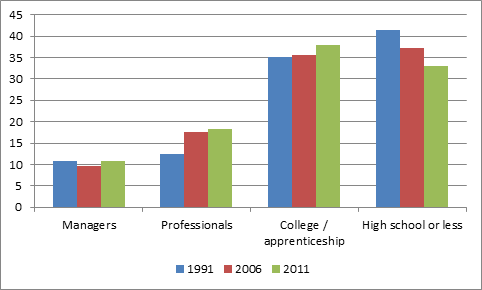

Got that? Good. Now figures 1 and 2 look at jobs by skill levels for women and men, respectively.

Figure 1: Distribution of Employed Women Aged 25-34 Across Skill Levels, 2011

Figure 2: Distribution of Employed Men Aged 25-34 Across Skill Levels, 2011

Interesting results. Aren’t people always telling us that young people are getting blocked on their career path by oldies? That sentiment doesn’t quite square with this data, which indicates that a greater proportion of under-35s are managers. Further, the increasing proportion of youth in professional jobs certainly contradicts the idea that universities are overeducating a generation.

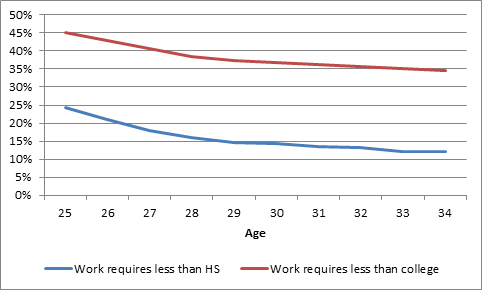

With respect to “overqualification” of university grads, specifically, the paper finds that 18% of university graduates aged 25-34 are in jobs requiring only high-school, and 40% are in jobs requiring college. But a substantial portion of that has to do with transitions to the labour market – these numbers are a lot higher for students in their 20s than in their 30s, as figure 3 shows.

Figure 3: Overqualification Levels by Age, 25-34 Year-Olds

Now, this still looks like a pretty significant level of overqualification. It’s slightly overstated with respect to graduates of Canadian universities; the presence of immigrant graduates of foreign universities, who tend to have much worse labour outcomes than graduates of Canadian universities, pushes the rates up by a couple of percentage points. But that still leaves about 15% of graduates in jobs with high-school level requirements, and about 36% in jobs with college-level requirements. Surely that’s evidence of over-production of graduates, right?

Well, no. Or, at least, no more than usual. Despite graduate numbers jumping by 50% between 1991 and 2011, the percentages of university graduates described as overqualified has remained rock-steady at these levels over 20 years, which suggests that expansion of university enrolments has been paralleled exactly by an expansion in jobs requiring graduates.

There is still the question of whether these numbers are too high, even if they aren’t increasing. It’s hard to say for sure. Some “overqualification” is structural – for instance, most Fine Arts graduates are, by definition, overqualified because NOC considers “artists” to require no more than a college diploma. Some “underemployment” outcomes will be by choice. And the rest? They might represent failure – or they might represent the beginning of the up-skilling of specific occupations, and thus, in fact, represent success.

More research needed, as the saying goes. But these results are encouraging.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post