A few weeks ago, the Parliamentary Budget Office put out a report (available here) on the sustainability of public finances. It’s an excellent little report, with some key implications for post-secondary institutions across the country. Today, I will discuss two points in particular.

The first key point has to do with the long-term sustainability of the finances of each level of government. Though this is poorly understood, the two levels of government have i) different sources of revenue and ii) different program responsibilities, each of which have respond differently to the prospect of demographic economic change. Briefly, provincial finances suffer a lot more from an aging population than federal ones do, mainly because they’re the ones on the hook for health care and social services.

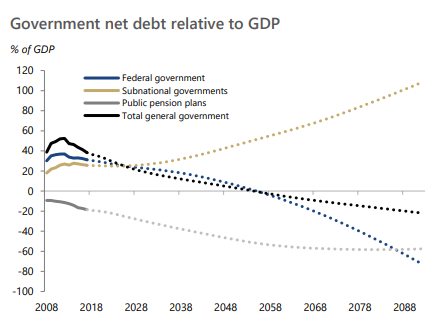

To get a sense of this, check out the graph below, which shows net debt as a percentage of GDP, projected out to 2088. Ceteris paribus, for governments as a whole, the story is positive – meaning as a country our debts as a proportion of the economy are declining, which is a good thing. It means we can afford to gently increase spending or decrease taxes over time. But while the federal position gets better as time goes on, and moves into negative net debt (i.e.. net surplus) sometime in the 2050s, the provincial (labelled in this graph as “subnational”) net debt position starts to look quite alarming from the 2030s onwards.

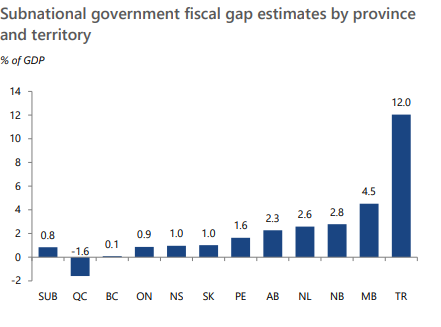

Now, this trend at the provincial level is not uniform: some are in a better position than others. The PBO report talks about this in terms of “fiscal gap” – that is, the reduction in spending or increase in taxation required to bring provincial finances into long-term balance. British Columbia is the only province which is more or less in balance; Quebec is actually in long-term surplus and will see its debt decrease over time (to anyone who lived in Quebec in the 1980s and 1990s, when the province was the fiscal equivalent of Greece or Venezuela, this is bewildering, but it tells you how seriously both Liberal and PQ were about fiscal rectitude over the last 20 years). Everyone else, though, has some work to do.

In places like Ontario, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, the issue isn’t out of control. One percent of GDP in those provinces equals $8 billion, $750 million and $415 million, respectively. That’s the size of the tax increase/spending cut required to future-proof the budget against demographic decline. But in other provinces? In Newfoundland, the tax increase/spending cut would need to be $800 million (and that’s not including dealing with the cost of dealing with the Muskrat Falls omnishambles). In New Brunswick it’s $960 million. And in Manitoba it is $3 billion, or a little over 17% of the current budget.

So, two big takeaways here. The first is that there is likely to be a significant fiscal re-balancing in Canada at some point in the 2020s or 2030s. It is untenable for one level of government to be in perpetual surplus and the other in perpetual deficit. This re-balancing could happen in one of three ways. The federal government could cut taxes and provinces could raise taxes. This is the simplest and cleanest possible solution but is sub-optimal from a provincial perspective because it requires them to take the political responsibility of raising taxes. Preferable from their point of view is to keep the status quo, but have the federal government send them ever larger no-strings-attached transfer payments. I think this is likelier, though as time passes the federal government will become more confident about demanding various types of strings, which could include various types of currently unthinkable accountability measures. The third possibility, which is theoretically possible but pretty unlikely, is that the provinces could upload certain responsibilities to Ottawa. Whichever form the rebalancing takes, it will presumably affect the way post-secondary education is financed.

The second takeaway is this: regardless of the form rebalancing takes, some provinces are in deep trouble. Over the long-term, government support levels for post-secondary education in most provinces, but especially Alberta, Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Manitoba are almost certain to decline. Institutions in those provinces need a) to get more control over revenue (particularly fees) and b) need to find ways to keep expenditure growth under control.

The good news? If you’re in BC, you can feel reasonably confident at least things aren’t going to get worse and in Quebec they might actually get better. Of course, all that extra fiscal room in la belle province just means there’s probably no political impetus to reform a needlessly-generous and regressive tuition fee subsidy, but I guess you can’t have everything.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post