Alberta has long been a fiscal outlier in Canada. It is by some distance Canada’s richest province (in the sense that household incomes per capita are the highest) and its provincial governments—mostly Conservative, but with a New Democrat interlude between 2015 and 2019—have long provided Albertans with public services to match. However, the one thing the Alberta government refuses to do is impose a sales tax or even a particularly imposing regime of personal taxes, preferring instead to ride the tiger of hydrocarbon royalty revenues. When oil and gas prices are high, this works very well; when they are low, government has a choice to make between cutting services and running a deficit. The previous (New Democrat) government under Rachel Notley went the deficit route. Last spring, Jason Kenney and the United Conservative Party were elected on a platform of, essentially, going the cuts route (technically speaking, the UCP platform promised zero change in public spending, but as everyone knows, with rising health care costs, zero change overall almost certainly means cuts in most non-health ministries).

Wisely, Kenney decided not to introduce a new budget immediately upon being elected, preferring to take the summer and early fall preparing the groundwork for a more comprehensive strategy. No doubt the timing of the federal election played a part too, with Conservatives across the country thankful the UCP did not introduce a round of aggressive budget slashing at a time Andrew Scheer was going around the country trying to reassure Canadians he would not do the same in Ottawa. In particular, he used the time to have former Saskatchewan NDP Finance Minister Janice McKinnon (probably the country’s most ferocious-ever deficit tamer, not that anyone in her party thanked her for it) head a commission to look into Alberta’s public expenditures and report back on how they could be made more efficient. This she duly did in early September (available here).

With respect to post-secondary education, McKinnon essentially made three points. The first was that there was not an awful lot of point to Alberta PSE spending, and that to some extent at least Alberta needed to adopt some type of performance-based funding system. The second was that a number of institutions seemed to provide education at very high per-student costs and that perhaps this needed to be reined in. There were subsequently many whispers about institutional mergers, particularly among regional colleges (the evidence that mergers reduce costs is pretty weak, but that’s the kind of evidence politicians rarely accept). The third was that compared to Ontario, Alberta institutions were more reliant on government funding, and perhaps Alberta could be more like Ontario, i.e. higher tuition fees. McKinnon did not, unfortunately, note the crucial difference that Ontario has a very generous student financial aid system while Alberta, ever since the Stelmach government cuts of 2010, has had the country’s stingiest one. This is something the Notley government chose not to fix, preferring wasteful tuition freezes to the more pressing job of providing extra money to students in genuine need.

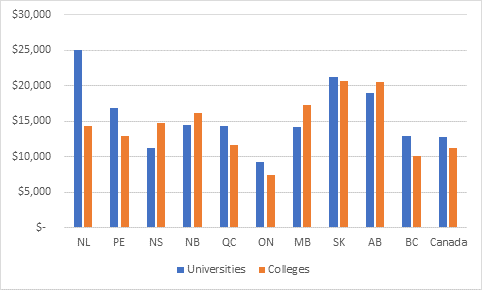

Now, the fact is, Alberta certainly does spend a lot on post-secondary education on a per student basis. It is pretty much the highest in the country, as shown below in figure 1. And what Alberta has been buying with that are, I would argue, three things. First, two public universities that are in the top-200 in the world by most reckonings, which is pretty impressive for a jurisdiction of fewer than five million people. Second, in NAIT and SAIT it has bought two polytechnics which are, again I would argue, among the best and most-industry focussed non-university higher education institutions in the world. And third, it has bought a system of regional colleges which provide access to high quality programs in relatively sparsely-populated areas. None of these things are cheap; indeed, the last one in particular on a per-student basis is quite prohibitive. But equally, the high cost is not in and of itself indicative of waste: successive Alberta governments wanted to buy these expensive items, and it did.

Figure 1: Provincial Government Expenditures per-student, by Institution Type, 2016-17

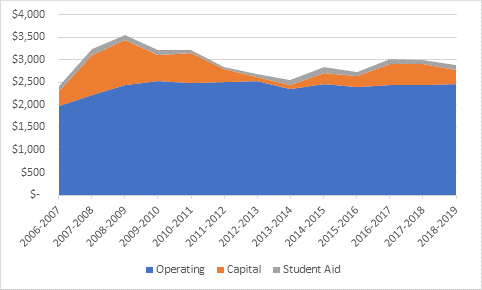

The problem is that as oil prices became less frothy, Alberta’s ability to pay for all this stuff has eroded. Figure 2 shows the Government of Alberta’s post-secondary education budgeted expenditures back to 2006 in real 2018 dollars. During the boom years, spending went up in real terms both on operating grants and—spectacularly—on capital (there was a point around 2008 where there were more cranes on the U of A campus than anywhere else this side of Beijing, and on the whole if some of your revenue sources are volatile, it’s a much better idea to blow the extra monies on buildings than to ramp up operating costs). But in terms of operating grants? Flat in real terms for a decade now. And for the last few years, the institutions were also stymied in their attempts to raise money from students by government-imposed tuition freezes.

Figure 2: Alberta Budgeted PSE Expenditures by Type, in millions of $2018.

So, with all this as background, we come to yesterday’s budget. Yes, there was a line in there committing the government to some kind of performance-based funding; no, the details weren’t there (which, you know, good because the Ontario Tories, by committing to quickly to details, ended up with some measures that were totally asinine). Yes, tuition fees are going up by a maximum of seven percent per year over next three years. Basically, that means the government of Alberta is going to make off with 100% of the increase in federal grants to low-income students that the federal Liberals promised in the manifesto they released a few weeks ago. Federalism FTW! Plus, for those not eligible for the low-income grant, their student debt—on average already the highest in the country due to a decade of policy neglect—will be even worse off, which in a province as rich as Alberta is totally unnecessary and speaks to poor priorities. Also, interest rates on the loans are going up slightly, from prime to prime plus one percent.

But the big one is the hit to institutional operating budgets: it’s big, much bigger than the initial headlines are letting on, but how big is difficult to tell because of the mindbogglingly opaque way Alberta reports PSE funding in its ministerial business plans. The Estimates for this year, 2019-2020 (i.e. the one that is already seven months over) are clear enough: a 5% decrease from last year’s actuals and a 7% decrease from budget-to-budget. This is, to be clear, a mid-year cut, which is always difficult to manage, but perhaps not impossible since this budget was so heavily trialed as a cutting budget. Also, this amount is not being distributed equally across institutions. Depending on an individual institution’s current position, the cut will be anywhere from 0% to 8% (this sounds a lot like punishing those institutions who have been most successful at cost control, but whatevs).

But it’s the medium term where things get scary. The multi-year Business Plan, unlike the Estimates, does not directly report government transfers to institutions, but rather includes all institutional expenditures in a single balance sheet. (Yes, it’s goofy, but Alberta’s done it this way forever, so roll with it.) Rather than a 5% cut, page 8 of the Business Plan shows about a 10% drop in “net operating results” (i.e. the amount governments have to cover after institutions have raised all their revenues, such as through tuition) for the current year. It goes on to suggest suggests that by 2022-23 the cut in net operating will be over 38% from last year’s actuals. Now, net operating results in the business plan aren’t quite the same thing as transfers to institutions in the estimates, but they’re close ($2.57B vs $2.27B). It’s hard to tell exactly what that means, but to me it sure raises the possibility that additional cuts of 20%-25% are baked into the plan for the next three years. Which, you know, WOW. That would make these the single largest set of cuts to Canadian institutions since the Depression. Neither the Alberta cuts of 1993 nor the Ontario cuts of 1996 were this big.

To me what was disappointing about this was less the cuts themselves than the framing. It’s perfectly OK for Alberta to say, “we want a set of post-secondary education institutions that costs the public less”. As noted above, the province historically chose to fund a luxury package of institutions, and it’s entitled to change its mind about what kind of system it wants. But unfortunately, I think the government chose to frame it as waste rather than choice, which is nonsense. Successive generations of Alberta governments understood perfectly well they were buying a Mercedes-level PSE system because they felt that was what the public wanted. To turn around and blame the Merc for not being a Honda serves no purpose other than to gaslight taxpayers and gin them up to blame public institutions for doing nothing more than what governments of the day asked them to do.

A shame, really.

PS: The blog will be off next week so I can get some sanity back in my life. See you all back here on Monday November 4th

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Here is the detail on cuts by institution:

https://www.alberta.ca/assets/documents/ae-campus-alberta-grant-funding.pdf

“…on the whole if some of your revenue sources are volatile, it’s a much better idea to blow the extra monies on buildings than to ramp up operating costs.”

There’s another possibility: build up an endowment, while keeping campuses small, with low overhead expenses. The situation of Alberta higher ed institutions mirrors that of the province as a whole, failing to put aside a sovereign wealth fund for when the boom inevitably ended.

Thanks for sharing this amazing post.