Long time readers may remember about six years ago I examined a program known as the Tennessee Promise, one of the earlier “free tuition” programs in the US. Technically, it was not a “free tuition” scheme, but rather what was known as a “last dollar scholarship”, meaning that after applying all other scholarships or need-based aid, the state brings the “net tuition” to zero. What I found was that if you looked just at students coming out of secondary school (the group targeted by the Tennessee Promise), was that in its first year, it appeared to have caused a) a 30% increase in 2-year-college going rates among recent high-school graduates, roughly half of which was diverted from other types of education and b) a 6.8% increase in transitions to all forms of colleges. However, based on a county-by-county analysis of transition rates, the increase did not appear to have occurred due to higher rates of college-going from poorer parts of the state.

So, I was intrigued to see a story from Inside Higher Education suggesting that the Tennessee college system was in dire enrolment trouble. What happened? Well, I went back to the source data (Tennessee has great source data on almost everything) to check the details, and what I found was quite interesting.

Figure 1 shows the long-term pattern of college attendance for those students who transition directly from high school. The blue and yellow lines represent 2-year institutions; the orange and green lines represent four-year institutions. Clearly, as I noted a few years ago, there was a big one-time shift towards two-year institutions and away from four-year institutions which coincided with the introduction with the Tennessee promise. At the same time, the overall transition rate jumped from about 56% to 63%.

Figure 1: Public In-State Public High School Graduate Enrolment by System, Fall 2011-Fall 2020

The situation largely stabilized within a year or so – in the sense that community colleges enrolment stayed high, and the high-prestige University of Tennessee stabilized its numbers almost immediately (one of the amazing things about this, from a Canadian perspective, is the idea that a prestigious university would pass up the possibility of increasing student numbers). But 2017 was the year unemployment in Tennessee fell to about 3%, which is where it has returned post-COVID. And that, apparently, ended the enrolment increase – the job market was simply too hot for some students to resist. Participation rates started to fall, and most of that fall was mostly concentrated in the 2-year sector.

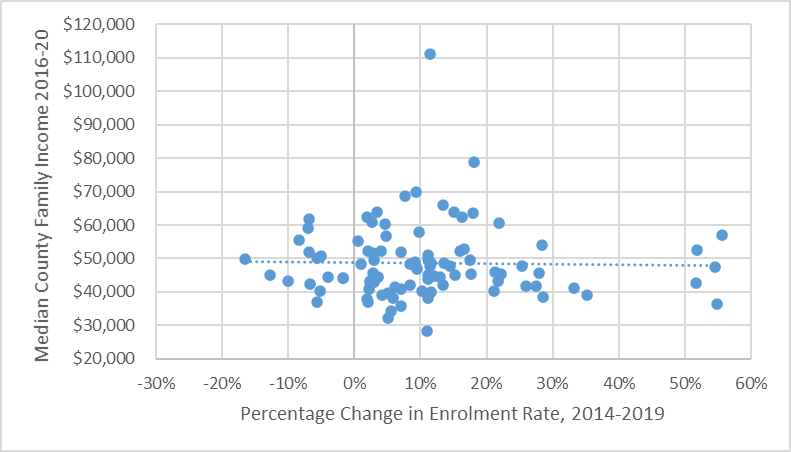

One thing that did not change much over time was the dispersion in changes in participation rates by county. Six years ago, I noted that the change in participation rates between 2014-15 was uncorrelated to median county income, which suggested that the beneficiaries were not primarily poorer students. Extending that analysis out to 2019 or 2020 (I did both, just to see if COVID many any difference) shows a similar pattern.

Figure 2: Percentage increase in college-going rate by county, Tennessee 2019 over 2014, vs County Median Household Income

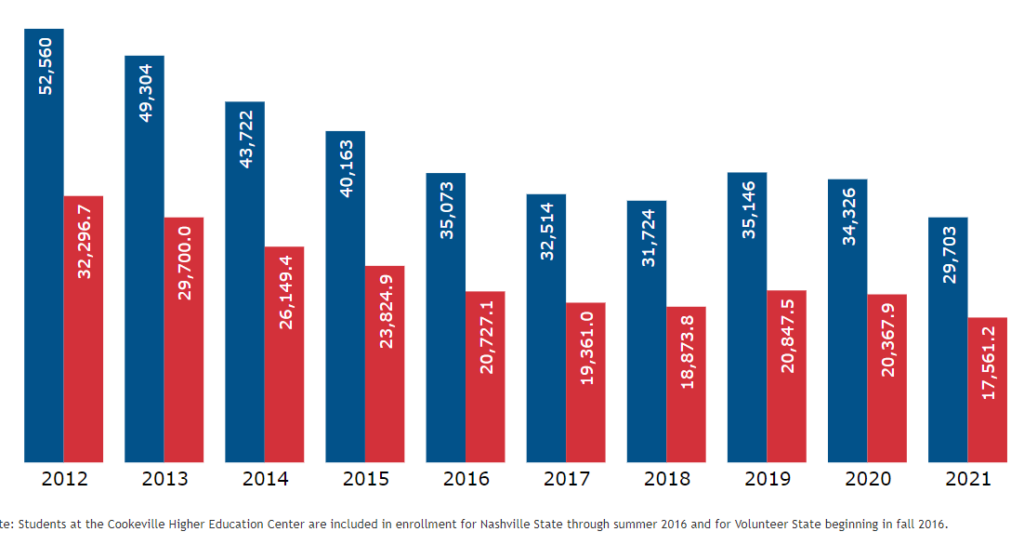

But these data points apply only to those students coming out of high school, which is only one part of the enrolment equation. If one examines enrolment in Tennessee community colleges of individuals over the age of 20, one gets a completely different picture of what’s been happening in the state. Essentially, enrolments for these students has been declining hand-in-hand with the unemployment rate for nearly a decade.

But surely part of the story is still about net price? Didn’t I just say that the Tennessee Promise was only for students leaving high school? Well, yes, I did. But back in 2018, the State of Tennessee created something called the Tennessee Reconnect Grant which extended basically the same offer to adult learners as well. The effect? Not great, as a recent evaluation of the program makes clear (go ahead: do a search for any provincial student aid program which has done a similar program evaluation…I’ll wait). COVID obviously played a role here, but that’s only part of the story.

In fact, the real story here seems to be quite different. Broadly, what we can make out from this are two things: community college enrolments are probably more sensitive to labour market conditions than they are to tuition and lowering tuition can have a temporary effect on relative preferences between 4- and 2-year colleges, but it may not last. In both cases, these suggest that one needs to be cautious about ascribing too large an effect to a reduction in tuition fees.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

We could also infer from the study that first requiring students to apply for money from everybody and their dog will minimize the effectiveness of free tuition programs, especially among lower income groups.

Still. Interesting report and discussion.