It’s been a long time since I’ve been as disappointed by an article on higher education as I was by the Star’s coverage of the release of the new HEQCO paper on teaching and research productivity. A really long time.

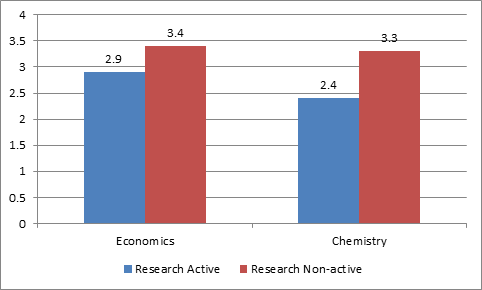

If you haven’t read the HEQCO paper yet, do so. It’s great. Using departmental websites, the authors (Linda Joncker and Martin Hicks) got a list of people teaching in Economics, Chemistry, and Philosophy at ten Ontario universities. From course calendars, Google scholar, and tri-council grant databases, they were able to work out each professor’s course load, and whether or not they were “research active” (i.e. whether they had either published something or received a tri-council grant in the past three years). On the basis of this, they could work out the teaching loads of profs who were research-active vs. those who were not (except in Philosophy, where they reckoned they couldn’t publish the data because there simply weren’t that many profs who met their definition of being research-active). Here’s what they found:

Annual Course Load by Research Active Status

To be clear, one course here is actually a half course. So the finding that “non-research-active” professors teach less than one course extra means that there are, in fact, a heck of a lot of non-research-active profs who teach no extra courses, and who teach exactly the same amount as professors who are research active.

For reasons of fairness as much as productivity, this seems like a result worth discussing, no? And yet – here’s where the disappointment comes in – that doesn’t appear to be where the main actors in this little drama want to go with the story. Rather, they appear to want to make irrelevant asides about the study itself.

Now I say “appear” because it’s possible they have more nuanced views on the subject, and the Star just turned the story into a he-said/she-said. I want to give them the benefit of the doubt, because the objections printed by the Star are frankly ludicrous. They amount to the following:

1) Teaching involves more than classroom time, it’s preparation, grading, etc. True, but so what? The question is whether profs who don’t produce research should be asked to teach more. The question of what “teaching” consists of is irrelevant.

2) Number of courses taught is irrelevant – what matters is the number of students taught. This is a slightly better argument, though I think most profs would say that the number of courses is a bigger factor in workload than the number of students (4 classes of 30 students is significantly harder than 3 of 40). But for this to be a relevant argument, you’d need to prove that the profs without a research profile were actually teaching systematically larger classes than their research-active counterparts. There’s no evidence either way on this point, though I personally would lay money against it.

Here’s the deal: you can quibble with the HEQCO data, but it needs to be acknowledged: i) that data could be better, but that it is institutions themselves who hold the data and are preventing this question from being examined in greater depth; and, ii) that this is the one of the best studies ever conducted on this topic in Canada. Kvetching about definitions is only acceptable from those actively working to improve the data and make it public. Anyone who’s kvetching, and not doing that, quite frankly deserves to be richly ignored.

16 Responses

Do you suppose what may be an inadvertent omission in the study is the role service plays in workload? How many of the research non-actives (let’s call them RNAs) are tasked with such duties as Chair or Program Director? Keep in mind that with so many uni admins preaching the “grow or die” mandate (esp. in A&H), that means introducing whole new programs. These require a great deal of setup before they are ready to start running. But, in sum, I wouldn’t consider the role of service and administrivia as a side issue here as it is bundled up in workload assignment.

Possibly. You;d need universities to open up their data on the subject to find out. Which they wouldn’t do – hence this methodology, which is indeed incapable of capturing this important facet of university activity.

More to the point, the only reason universities (meaning upper administration, for our purposes here) would keep such information on tenured faculty would be if they intend to somehow discipline them. Which they might be empowered to do, but certainly aren’t qualified to do.

It is a credit to their humility if the overhead expenses keep no track of so-called “research productivity.”

It may very well be the best study ever done of its kind in Canada, but that definition of “research active” sounds made-up to me. Why 3? Why not 5? Why not 2? They left Philosophy out because their definition gave them results that didn’t eyeball right. Not a very rigorous way to define anything.

To be clear, they actually offered stats using definitions at the 1-year, 2-year and 3-year marks. You could choose which one you want, though I think the three year one makes most sense.

I suppose you’ll dismiss this as “kvetching,” but I do have three objections to the methodology, or rather to its underlining assumptions; to wit:

1. That research is necessarily reflected in publication and grantsmanship over a three-year period;

2. That it is the business of government, universities or anyone else to tell tenured faculty how to spend their time;

3. That teaching, research and service should be divided and measurable in the first place.

For the first, one need only think of any intellectual one admires who spent time in the wilderness. Fernand Braudel took fifteen years to write “Mediterranee,” probably the most important book published in twentieth-century French historiography. Professor Sir Isaiah Berlin published very little between his early work on Russian intellectualism and his stardom as a commentator for the BBC. Peter Higgs is on record as saying that he seldom had anything to contribute to the research assessment exercise. Telling people that they must be either 1. doing something expensive and endorsed by an underfunded granting council or 2. doing something picked up by google scholar would be to rob the western academy of some of its greatest minds. People who have nothing to say at the moment should be left alone to stare out the window until they do.

Secondly, the purpose of tenure is supposed to protect intellectual freedom. Telling people when and what they have to produce is a command, and therefore its opposite. Besides, no-one but one’s colleagues are qualified to judge one’s research. Certainly the writers of this report are too ignorant to know the proper indices of each field, and so fall back on google scholar. The report implies a system of administrative fiat rather than collegial governance.

Finally, the study separates teaching and research, whereas the idea of a university is to draw them together. The implication seems to be that teaching is a punishment to be visited upon those who don’t pump out articles regularly enough, whereas the ideal is to maintain and share one’s expertise. We’re confusing measures of productivity with the life of the mind. Numbers are not things, but their signs.

As a final note, I should say that I find myself enormously more productive after receiving tenure, when the pressure is off. Commanding people to produce is likely to have a paradoxical effect, producing writer’s block, not great ideas. At most, it will add to the cultural and scientific noise, to all those unread articles that everyone complains of, not to intellectual growth.

1. If Braudel were writing today I;m pretty sure he could turn a couple of those chapters into journal articles along the way.

2. Intellectual freedom gives you freedom of research and (to a degree) of teaching. it doesnt give you freedom *from* research and teaching responsibilities

3. Teaching and research may be mutually reinforcing (though frankly there’s precious little empirical evidence of that), but they are at least to some degree mutually exclusive in terms of time. Pretending that;s not true isn’t on.

1. Maybe. But it’s none of the administration’s business if he does or not. Certainly, it would still be research.

2. It isn’t true freedom to research if it isn’t freedom to research something that won’t produce a measurable result on google docs. You’re just confusing the actual research with its measurable product.

3. I listened to a recording of a play I’m both teaching in class and publishing on in an editted collection while coming to work a couple of days ago. Was I researching or teaching? The true life of the mind is indivisible. It’s only divided for purposes of administration, which we need less of, not more.

I am shocked, SHOCKED, that an organization that takes HEQCO contracts would be so effusive in their praise for one of their papers.

Oh lord. Think up something more original. And check your facts – I can be quite critical of HEQCO papers: https://higheredstrategy.com/comparing-delivery-costs/

The email version of the post (that I got) is missing the “appear” paragraph, which is pretty important to the post.

The OCUFA response was predictable, it just avoided the issue.

The study seems flawed for a couple of reasons.

First, the study’s definition of research activity is overly restricted. It notes, “For economics and philosophy, we include only articles published in peer-reviewed journals. We do not include other research activity such as books, book chapters, conference presentations, case studies, reviews and contributions to workshops.”

In other words, the study doesn’t consider two of the main venues in which SS + H profs typically publish: books and book chapters. To omit books seems a particular problem. Books are typically understood as equivalent to several peer-reviewed articles. In other words, it could be that the Philosophy profs they look at haven’t published a peer-reviewed article in the past three years but may have published 1 or more books.

Book chapters, too, usually are peer-reviewed (though perhaps less anonymously). Conference papers, too, tend to reflect current research activity, even though they have less weight than a peer-reviewed article or book chapter. To discount these forms of publication skews the data. To be fair, the study notes that changing its definition of research activity would change the results. But this restrictive definition of research is a major problem with the study as published.

Second, counting grants as research introduces a problematic comparison. SSHRC grants are awarded at a 21% success rate while NSERCs are awarded at a 59% success rate. As a result, SSHRC depts with equivalent faculty complements as NSERC depts will have, on average, substantially fewer grants and so appear less “research active.” I.e. a SSHRC department of 10 is likely to have 2 grants awarded to it in any given year while an NSERC department of 10 is likely to receive 6. The NSERC department appears 3 times more “research active” simply on the basis of the systemic differences in agencies’ awarding of research grants.

Hi there. Thanks for writing

I;m not sure how either of those invalidate the study. WRT definition of research, it;s not going to affect economists, whose primary form of communication *is* peer-reviewed articles. It might affect philosophy, but they effectively admit that when they looked at results and decided to exclude them from the comparison exercise. WRT SSHRC vs. NSERC, that would be relevant if the purpose of the paper is to compare what was going on between departments. But that’s not what this study does. It’s looking at differences in teaching activity according to research output *within* each field of study. So the differences are already controlled for.

While you’re right that the study excludes Philosophy, the public reception or administrations’ use of the study may not grasp that. Even your post implies Philosphy is not a research-active department: “On the basis of this, they [the study’s authors] could work out the teaching loads of profs who were research-active vs. those who were not (except in Philosophy, where they reckoned they couldn’t publish the data because there simply weren’t that many profs who met their definition of being research-active).” The comment implies that the problem is with the profs rather than with the definition.

Likewise, the study does compare implicitly the different departments. At my institution, teaching loads in the SS + H Faculties (5 courses) are higher than in the Sciences (4 courses), The difference in teaching load is justified, to an extent, by comparisons such as those the study implies.

Such comparisons between departments are increasingly used by universities. My own campus is adopting a “driver-driven” budget model, in which more funding will be provided to departments that show research productivity by way of winning grants. This just seems a round-about way to shut down the humanities, or force humanities professors to teach unsustainable loads and become mere service departments for the wider campus.