Some things never change. Specifically, the demands of the academic left in Canada.

Take, for instance, the “Education for All Campaign” which was launched in late January. A joint project of the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) and the National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE), the campaign produced this new report, which is not a new report in the sense that it puts forward any new policy proposals or indeed puts much thought into any of the argumentation behind them.

Or, take for example, the Royal Society of Canada’s Report of the Working Group on the Future of Higher Education, entitled Investing in a Better Future: Higher Education and Post-COVID Canada. This one is maybe the ultimate example of people arguing for the things they have always argued for (roughly: “give us money and leave us alone”), but prefacing it with the words “Because of COVID-19 we must…”

The basic argument in both papers is: post-secondary education is excellent. Really, really superb for the economy and for individual social mobility, important for communities, society, etc. BUT: “access to PSE is increasingly a challenge”, “PSE workers [are] being forced into increasingly precarious employment”, “the system exploits international students”. And therefore, “it is time for a NATIONAL STRATEGY” (though only if said strategy involves lower tuition fees, more public funding, fewer casual staff….you get the idea). Basically, more public money with fewer strings = good.

Broadly, there is nothing wrong with arguing this. There’s no doubt that more money would make life easier in for those in higher education. But in fact, though the authors of these two reports seem not to recognize it, their first priority with public money is not to make it easier to run universities and colleges, but to hand it over to students to reduce their costs. Because – and the argument does not get a whole lot more sophisticated than this – tuition is a lot higher than it was 30 years ago and this is bad. The fact that university enrolments have doubled over the past thirty years does not get a look in here. Neither does the fact that the gap between rich and poor in terms of access is not increasing. The entire argument is basically a play off a classic terrible soup/small portions borscht-belt joke: tuition is so high! And so many people are choosing to pay it!

The problem with all of these arguments is that they seem largely ignorant of – or at least impervious to – actual facts. I quite enjoyed the argument that tax-based aid to students is “regressive”. In fact, since the overwhelming majority of tax credits in the system are for tuition fees, it means any aid delivered via tax credits is exactly as progressive as a reduction in tuition. There is literally no difference. To say this in a document which pushes for lower tuition is like flashing an enormous sign saying I HAVE NO CLUE ABOUT THE SUBSTANCE OF MY OWN ARGUMENTS.

Similarly, the stuff about “increasingly casualized labour forces” doesn’t actually stand up to scrutiny. As CAUT data actually shows, the percentage of people in universities who consider teaching to be their primary job who are either part-time or temporary hasn’t changed in the last thirty years (data at the link is a little out of date but feel free to check chapter 2 of HESA’s annual State of Post-Secondary Education publication which updates these tables and shows no change), and the evidence cited on the growth of casualized labour is suspect. The story is a bit different in colleges – at least in Ontario, the one province where we have good data – but for some reason this isn’t where the focus of the argument lies.

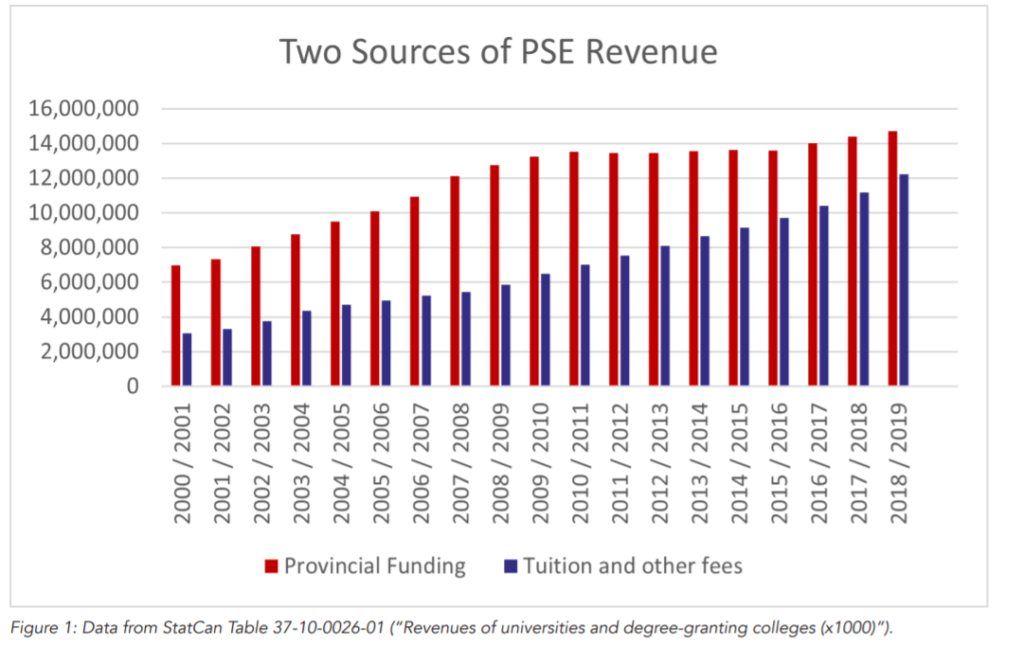

If you want to see this problem in full effect, read pages 16 of the Royal Society report, which bemoans “chronic underfunding”, and how “government funding for the academic funding of universities and colleges has declined significantly since the last century”. This is followed, on page 17, by the following graph, which quite clearly shows that provincial funding has doubled in nominal terms since the turn of the century.

What I find most discouraging about all this stuff is not what they argue but how they argue it. Both argue for more access, but neither explores data on how best to achieve it. Data does not matter, alternatives are not explored, and as a result the only option for expanding access given is “lower tuition” even though targeted grants are cheaper and more effective.

It’s all just cant. The same thing, over and over again, decade after decade, with no serious attempt to analyze the data as it comes in. And I mean sure, I get the difference between disinterested research and advocacy research. But for God’s sake: if you’re representing academia as a whole, you should probably at least pretend the data matters. In these two documents, facts are instead used the way a drunk uses a lamp-post: for support rather than illumination.

Disappointing, to say the least.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

A quick note: “the percentage of people in universities who consider teaching to be their primary job who are either part-time or temporary” is a very different metric from the percentage of course sections taught by part-time or temporary faculty, which is what people actually have in mind. More often than not, part-time faculty (especially in the humanities and social sciences) cobble together heavier-than-full-time teaching loads one stipend at a time, possibly from multiple institutions.

Right, but for a whole bunch of reasons, that’s an absolutely terrible measure. The majority of adjuncts teaching course-sections are in fields like law and nursing where the PT instructors have full-time jobs professional already. See here: https://higheredstrategy.com/mind-blowing-ontario-academic-staffing-data-part-2/

Thanks for that. It’s actually really interesting data. Perhaps the fundamental cross-purposes here is that individual readers are going to look at that aggregate data and honestly find that it doesn’t compute in comparison to the individual institutions that they’re personally familiar with. But that’s the thing, right? There’s no such thing as an average university, just a lot of possibly widely divergent individual data points, but that doesn’t obviate the need to find large-scale understanding. Thank you for engaging with an anonymous rando!

One other thing: how much do national totals really represent the reality on the ground if, for instance, a small number of U15s are getting a nominally disproportionate lion’s share of the additional funding as a result of various targeting mechanisms?

There’s a qualitatively similar issue, too, with the observation (from an earlier post) that Canadian funding of PSE has been almost perfectly stable over the last decade or so: is this actually such a meaningful observation when that apparent stability is the result of independent funding upturns and downturns in the various provincial systems accidentally cancelling each other out?

[None of this is to absolve anyone of the need to engage more rigorously with the relevant data, but large-scale metrics can have a very complicated relationship with actual realities on the ground.]

Funding students directly via refundable tax credits would help.

https://theconversation.com/after-covid-19-funding-post-secondary-students-directly-could-create-more-accessible-education-152112