Hi all. Just a quick one today, this time on some data I recently got from StatsCan.

We know a fair a bit about student debt in Canada, especially with respect to distribution by gender, type of institution, province, etc. (Chapter 6 of The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada is just chock full of this kind of data if you’re minded to take a deeper dive). But to my knowledge no one has ever pulled and published the data on debt by ethnicity, even though this data has been collected for quite some time through the National Graduates Survey (NGS). So I ordered the data, and here’s what I discovered.

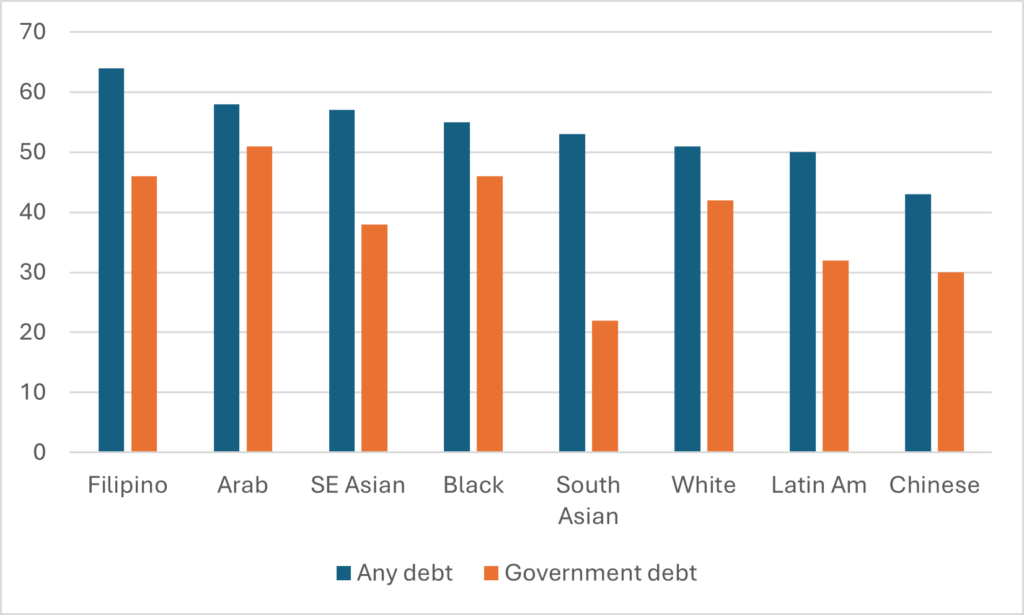

Figure 1 shows incidence of borrowing for the graduating class of 2020, combined for all graduates of universities and graduates, for the eight largest ethnicities covered by the NGS (and before anyone asks, “indigeneity” is not considered an ethnicity so anyone indicating an indigenous ethnicity is unfortunately excluded from this data… there’s more below on the challenges of getting additional data). And the picture it shows is…a bit complex.

Figure 1: Incidence of Borrowing, College and University Graduates Combined, Class of 2020

If you just look at the data on government loan programs (the orange bars), we see that only Arab students have borrowing rates in excess of 1 in 2. But for certain ethnicities, the borrowing rate is much lower. For Latin American and Chinese students, the borrowing rate is below 1 in 3, and among South Asian students the borrowing rate is barely 1 in 5. Evidence of big differences in attitudes towards borrowing!

Except…well when you add in borrowing from private sources (e.g. from banks and family) so as to take a look at overall rates of borrowing incidence, the differences in borrowing rates are a lot narrower. Briefly, Asian and Latin American students borrow a lot more money from private sources (mainly family) than do Arab students, whites, and Blacks. These probably come with slightly easier repayment terms, but it’s hard to know for sure. An area almost certainly worthy of further research.

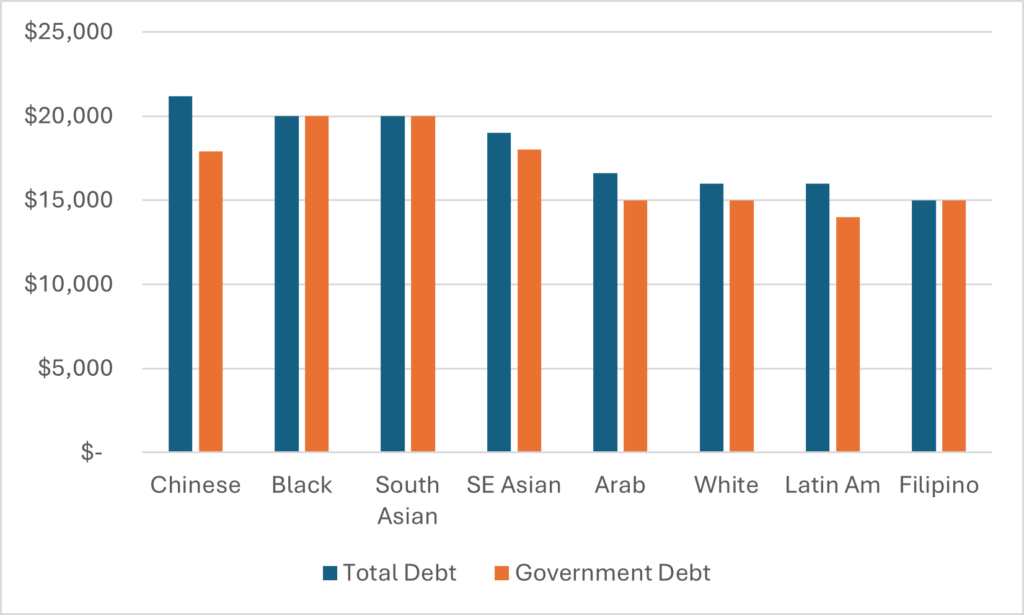

There is a similarly nuanced picture when we look at median levels of indebtedness among graduates who had debt. This is shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Median Borrowing, College and University Graduates Combined, Class of 2020

Now, there isn’t a huge amount of difference in exiting debt levels by ethnicity: the gap is only about $6,000 between the lowest total debt levels (Filipinos) and the highest (Chinese). But part of the problem here is that we can’t distinguish the reason for the various debt levels. Based on what we know about ethnic patterns of postsecondary education, we can probably guess that Filipino students have low debt levels not because they are especially wealthy and can afford to go to post-secondary without financial assistance. But rather because they are more likely to go to college and this spend less time, on average, in school paying fees and accumulating debt. Similarly, Chinese students don’t have the highest debt because they have low incomes; they have higher debt because they are the ethnic group the most likely to attend university and spend more time paying (higher) fees.

(Could we get the data separately for universities and colleges to clear up the confound? Yes, we could. But it cost me $3K just to get this data. Drilling down a level adds costs, as would getting data based on indigenous identity, and this is a free email, and so for the moment what we have above will have to do. If anyone wants to pitch in a couple of grand to do more drilling-down, let me know and I would be happy to coordinate some data liberation).

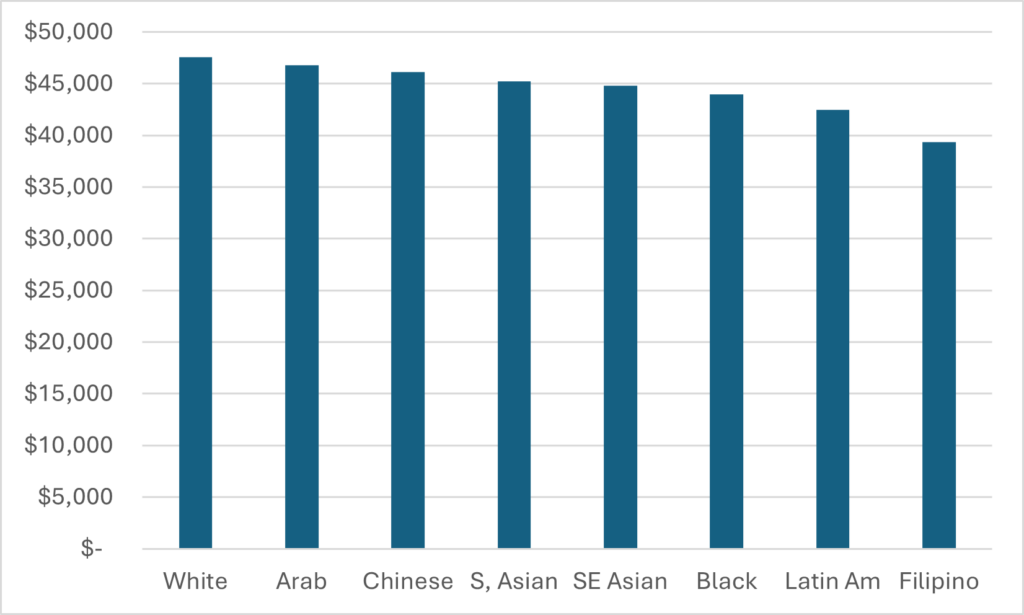

It is also possible to use NGS data to look at post-graduate income by debt. I obtained the data by in fairly large ranges (e.g. $0-20K, $20-60K, etc.), but it’s possible on the basis of that to estimate roughly what median incomes are (put it this way: the exact numbers are not exactly right, but the ordinal rank of income of the various ethnicities are probably accurate). My estimations of median 2023 income of 2020 graduates—which includes those graduates who are not in the labour market full-time, if you’re wondering why the numbers look a little low—are shown below in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Estimate Median 2023 Income, College and University Graduates Combined, Class of 2020

Are there differences in income here? Yes, but they aren’t huge. Most ethnic groups have median post-graduate incomes between $44 and $46,000. The two lowest-earning groups (Latin Americans and Filipinos) re both disproportionately enrolled in community colleges, which is part of what is going on in this data (if you want disaggregated data, see above).

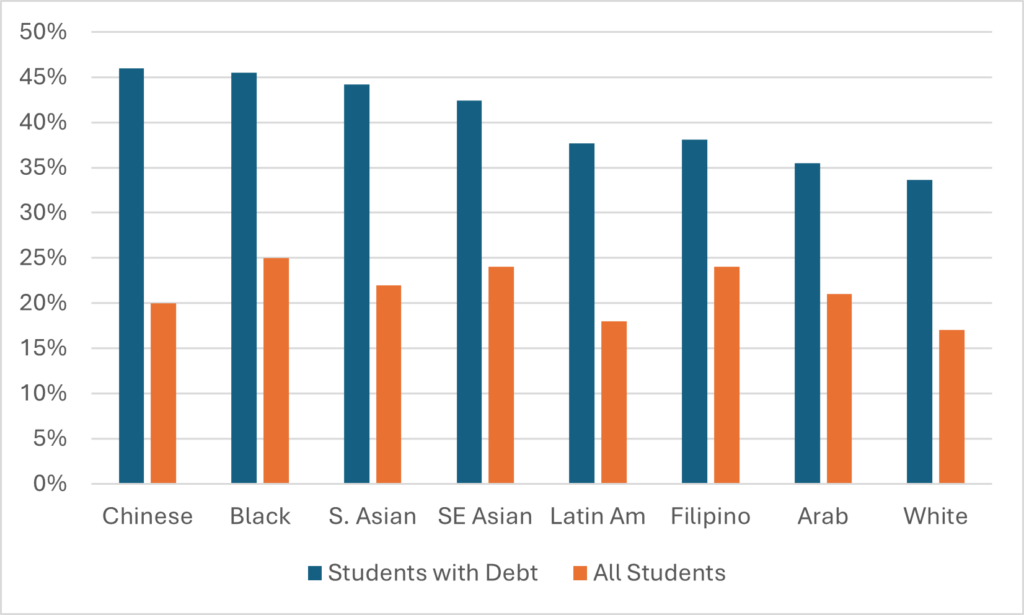

Now, the data from the previous graphs can be combined to look at debt-to-income ratios, both for students with debt, and all students (that is, including those that do not borrow). This is shown below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Estimated Median 2023 Debt-to-Income Ratios, College and University Graduates Combined, Class of 2020

If you’re just dividing indebtedness by income (the blue bars), you get a picture that looks a lot like Figure 2 in debt, because differences in income are pretty small. But if you are looking at debt-to-income ratios across all students (including those that do not borrow) you get a very different picture because as we saw in Figure 1, there are some pretty significant differences in overall borrowing rates. So, for instance, Chinese students go from having the worst debt-to-income ratio on one measure to being middle of the pack on another because they have relatively low incidence of borrowing; similarly, students of Latin American origin go from being middle-of-the-pack to nearly the lowest debt-to-income ratios because they are a lot less likely to borrow than others. Black students end up having among the highest debt-to-income ratios not because they earn significantly less than other graduates, but because both the incidence and amount of their borrowing is relatively high.

But I think the story to go with here is that while there are differences between ethnic groups in terms of borrowing, debt, and repayment ratios, and that it’s worth trying to do something to narrow them, the difference in these rates is not enormous. Overall, it appears that as a country we are achieving reasonably good things here, with the caveat that if this data were disaggregated by university/ college, the story might not be quite as promising.

And so ends the first-ever analysis of student debt and repayment by ethnic background. Hope you found it moderately enlightening.