Rejoice, all! For today is the publication for The State of Postsecondary in Education, 2023, your annual statistical guide to all things in our sector. This year’s edition does not contain any new chapters or appendices, but we have expanded coverage of certain matters related to the student body, particularly with respect to gender and to international students. With hundreds of pages and graphs, I know you’re going to be up all night reading it. Try not to strain yourselves.

As always, the exercise of trying to produce a statistical almanac is beset by two things: the normal delay it takes to get data out of institutions and Statistics Canada’s inability to beat almost any other country in processing such data (currently, the most recent StatsCan data on enrolments are three years out of date). These kinds of statistical analyses are always more exercises in looking backward than forward. To look forward – or even to make reasonable inferences about the present – it is necessary to engage in some rough estimating. So, take the data in the essay that follows as approximate – the best that current data allows.

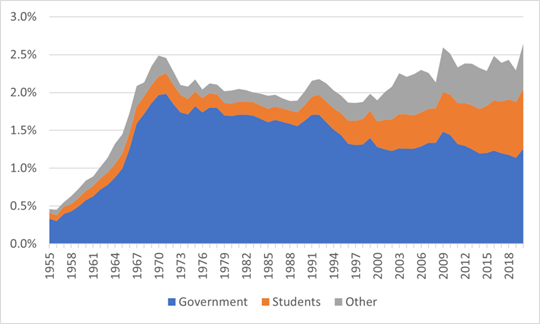

Looking back over a span of about 70 years, long-term patterns emerge. Between 1955 and 1970, postsecondary institutions quintupled in size as a percentage of the entire economy, from about 0.5% of GDP to 2.5%. That was the “golden” period of Canadian higher education: whatever universities and the few colleges asked for, they got. Public expenditures on postsecondary education – again, almost entirely universities – reached 1.9% of GDP. Since then, the history of postsecondary education funding breaks into two periods. From around 1970 until the late 1990s, public funding and total funding fell in lockstep. Then, as the 1990s went on, institutions began exploiting private sources of funding, not just to offset declining funding but to increase funding overall.

Figure 1: Total Institutional Income as a Percentage of GDP, by Source, Canadian Universities and Colleges, 1955-56 to 2020-21, in constant $2022

The long-term picture in Canada is thus a story of firmly pan-partisan public neglect – but also a story of institutional resilience and entrepreneurship. But at what cost? And how long can this last? To answer this question, it is worth looking at Ontario, which has long been in the forefront of defunding higher education.

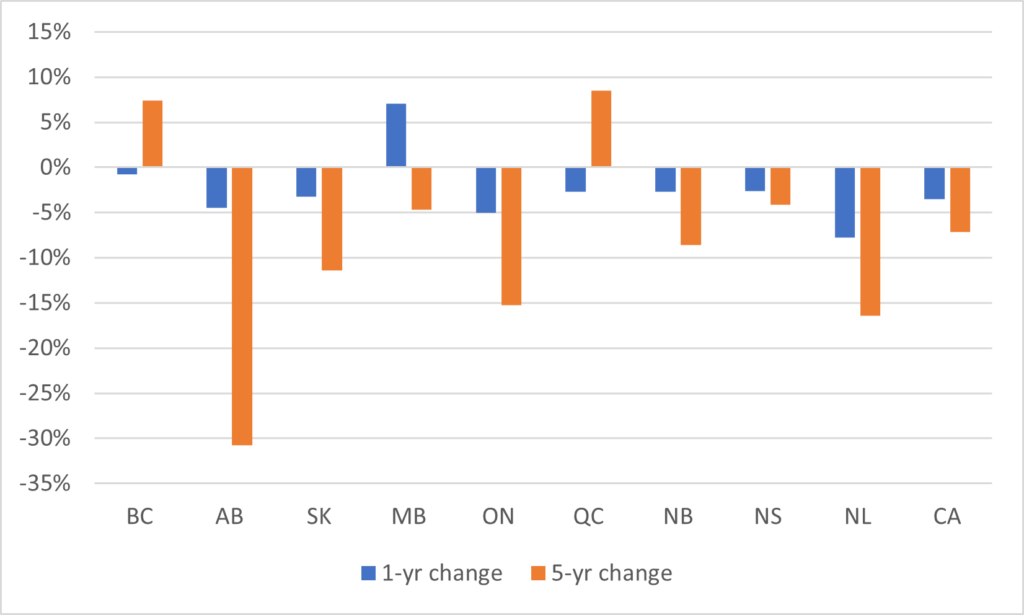

Over the past few years, two governments in Canada have gone beyond all others in reducing funding to postsecondary education. The more-noted effort was that of the Government of Alberta, which reduced budgeted funding to postsecondary education by 31% in real terms between 2019-20 and 2023-24. This was indeed a brutal cut, and an unequally distributed one at that, with rural community colleges receiving a lesser cut and the University of Alberta a larger one. But at the same time, Alberta began the process at a level of funding which was well-above the Canadian average: even after the cuts, Alberta per-student institutional funding levels were still close to the national average (slightly above for colleges, slightly lower for the universities).

Figure 2: 1- and 5-Year Change in Budgeted Transfers to PSE Institutions, by Province, 2023

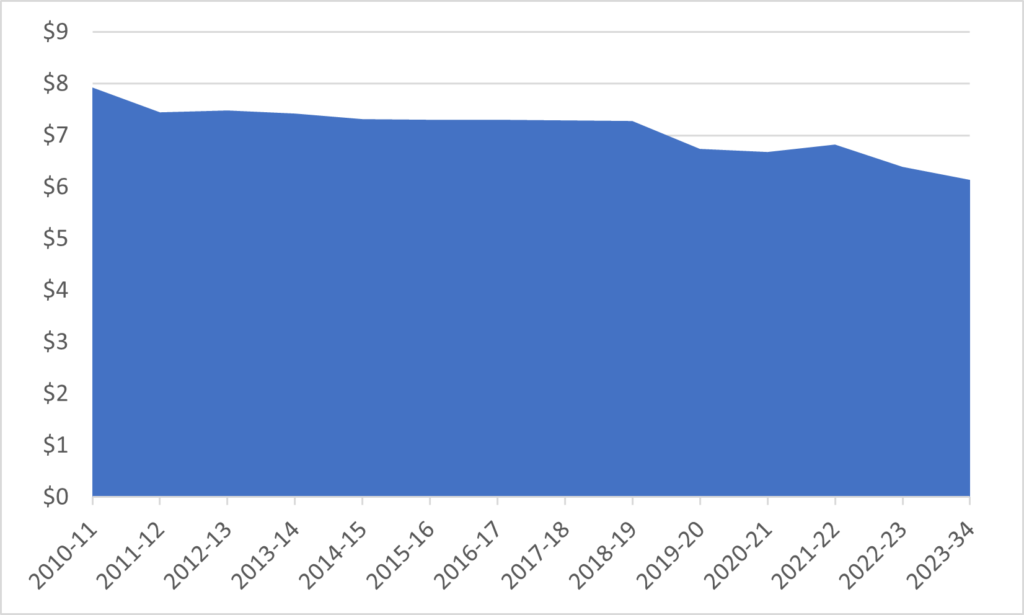

It is a different story in Ontario, which has been dead-last in institutional funding for higher education for something like 38 out of the last 40 years (it briefly rose to 9th place for a couple of years during the administration of Dalton McGuinty). It is, without a doubt, a province where underfunding institutions is a pan-partisan affair. In terms of government grants, the present government is continuing to freeze institutional grants in nominal terms and allowing inflation to erode the value of the contribution.

Figure 3: Institutional Income from Provincial Government Sources, Ontario 2010-11 to 2023-24, in real $2023.

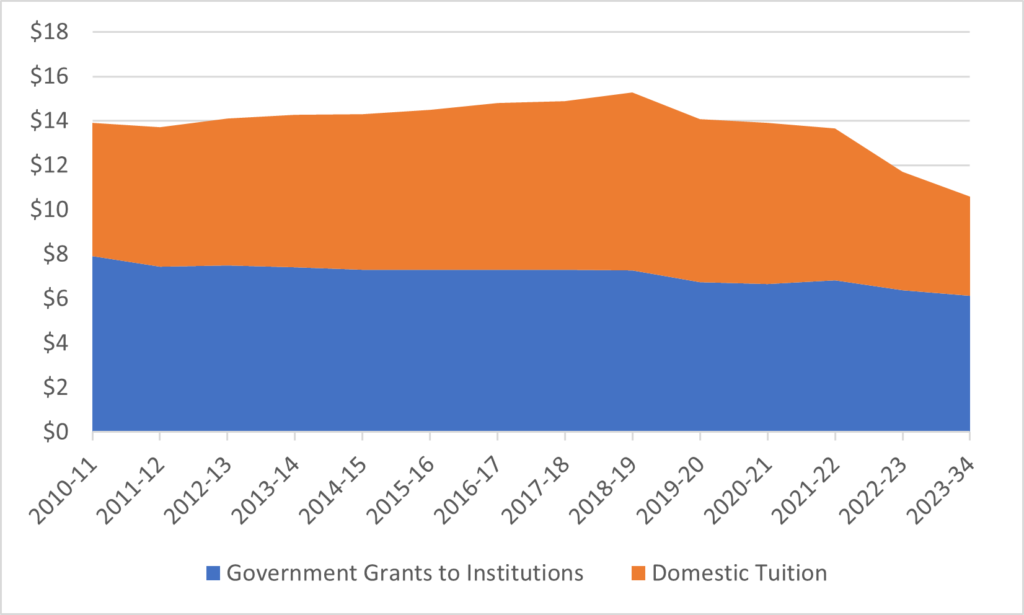

What is novel about the current Ontario government’s approach to higher education funding is the position it has taken on tuition fees. It imposed an across-the-board cut of 10% on institutions in 2019 and has left fees frozen at that level even since. Ontario is hardly the first province to freeze or reduce tuition: but in no other province which took this route was domestic tuition fees a larger funding source for institutions than government grants. In other words, the erosion of fee income – exacerbated by high inflation and a significant decline in domestic student numbers in the college sector – had a much more significant effect in Ontario both compared to other provinces and compared to the loss of income from the provincial government. As shown in figure 4, in inflation adjusted terms, Ontario colleges and universities have lost about 31% of their “government controlled” income (i.e., provincial grants plus domestic fees) in the five years since the Ford government came to power.

Figure 4: Institutional Income from Provincially controlled Sources, by type, Ontario, 2010-11 to 2023-24, in real $2023.

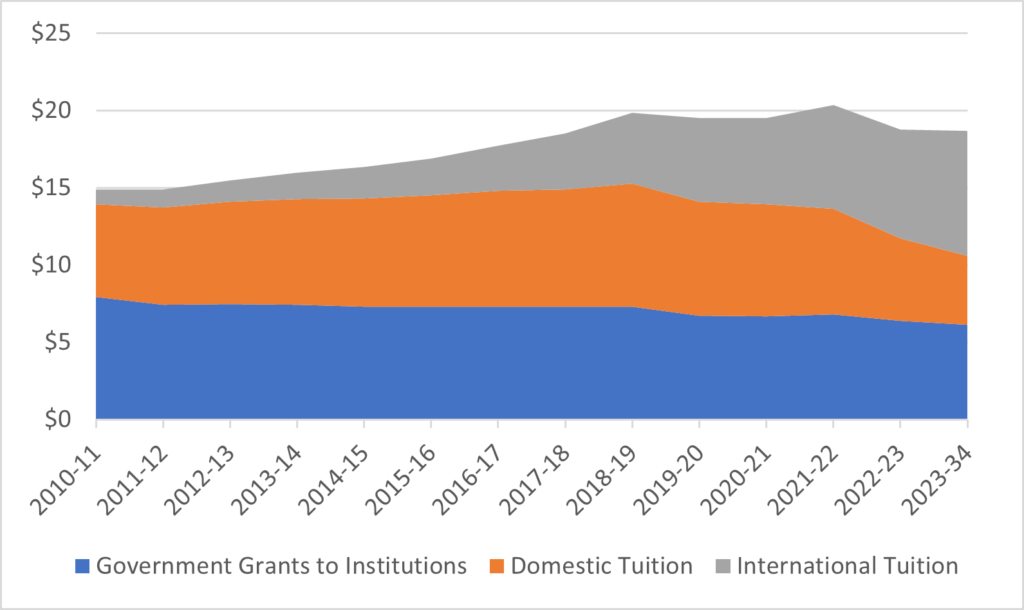

Faithful readers of this blog will not be shocked to discover how institutions coped. While institutions had already discovered that international students were a handy source of extra income in the early-to-mid 2010s, when the cuts began, they rapidly expanded international enrolments to backfill the missing money from domestic funding. Thus, as shown in figure 5, while income from international students has nearly doubled since 2018, total institutional income (excluding things like ancillary services, donations and investment income) is down slightly over the past few years.

Figure 5: Institutional Income from Government Sources and Tuition, Ontario 2010-11 to 2023-24, in real $2023.

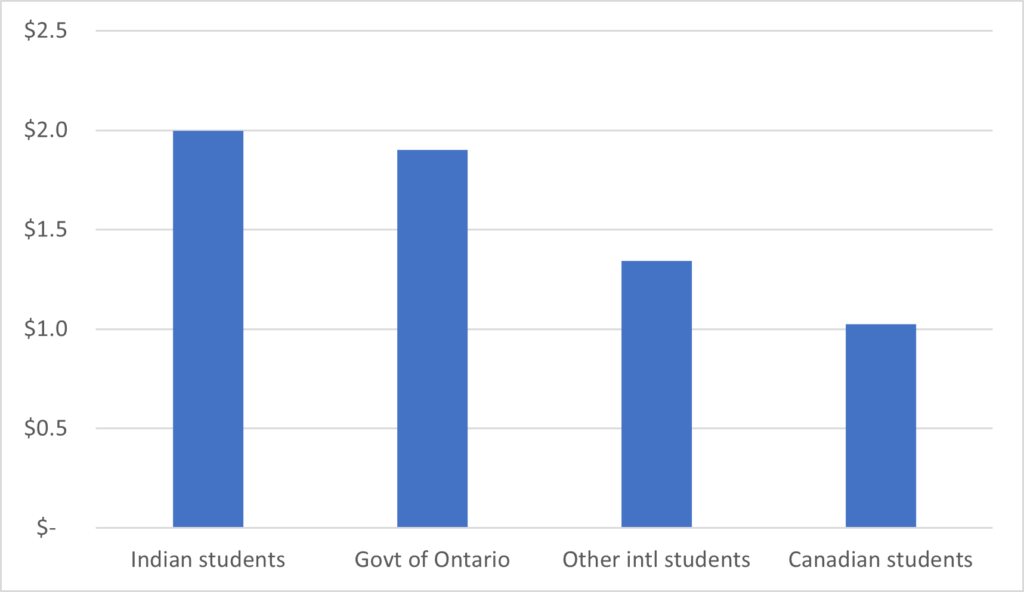

Nowhere are the effects of this transformation more obvious than in the Ontario college sector, where international students are expected to make up over half of the student body in 2023-24. Given that tuition for international students is something like three times what it is for domestic students (exact data is difficult to pin down because Statistics Canada chooses not to track tuition fees at the college level), that means that something like 76% of all tuition fees in the sector come from international students. And as figure 6 shows, since a majority of these international students come from India, it turns out that Indian students not only contribute twice the amount of money to the college system, on aggregate, that Canadian students do, they also contribute slightly more than does the Government of Ontario.

Figure 6: Estimated Institutional Operating Income by Source, Ontario Colleges, 2023-24, in $Billions

Numbers like these tend to induce shock. How can it possibly be that Indian students are paying more into the system that Queen’s Park? The answer is simply this: Ontario institutions, faced with deep cuts in income, have acted precisely the way the government asked them to – that is, by acting entrepreneurially and securing new forms of revenue. This isn’t a mistake: this is exactly what the Ontario government requires.

Now Ontario is an outlier. No province has underfunded postsecondary education more, and no province’s institutions have found so many ways to raise money from private sources. On a per-student basis, the province funds universities at 57% of the average of the other nine provinces; on the college side it is a mere 44%. It is tenth out of ten in every inter-provincial comparison of financing. Merely to get the province to reach ninth place among provinces for funding of colleges and universities requires an additional investment of $3.6 billion per year. To raise spending to the average of the other nine provinces requires $7.1 billion per year in additional funding. Ontario’s funding situation is, in a word, abysmal.

That said, with the possible exception of Quebec, every province is heading in the same direction as Ontario. Revenues are increasing or staying stable, but they rely on increasingly variable and costly sources of funding. While the system itself seems healthy, and many individual institutions are prospering like never before, some institutions are also more precarious. Laurentian University, which famously filed insolvency proceedings in early 2021 and only emerged from it in late 2022, may be the first of many institutions to go to the wall.

Canada is not Ontario, but many parts of the country might replicate these patterns, soon. Avoiding this fate requires a reversal of 45 years of disinvestment by governments. This will not be easy. This policy of gradual disinvestment is not an artefact of a particular government or ideological fad, it is the product of a profound consensus among Canadian governments, both federal and provincial, that postsecondary education is not a worthwhile investment. Similarly, the obsession with tuition fee freezes is an outgrowth of the belief that consumer convenience (or, more broadly “affordability issues”) is more important than the health of important social institutions such as colleges and universities. This, again, is a long-held preference of all political parties, presumably based on polling which says it is popular.

Nothing the sector has done in the past four decades to demonstrate relevance has worked to deflect governments from their determination to disinvest. Some radically new strategies are required if the entire country is not to end up like Ontario.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

The value you contribute to post-secondary in Canada is hard to overestimate. Thank you!

Hear, hear!

“Nothing the sector has done in the past four decades to demonstrate relevance has worked to deflect governments from their determination to disinvest.”

The problem, I think, has to do with the term “relevance.” If you want relevant job skills, that probably means something that will cease to be relevant in a few years, and which institutions build for the secular timescale can’t be expected to cater to. If you want relevant research, that means ignoring entire fields which aren’t obviously useful.

I realize it’s hard to explain that universities improve society by pursuing what often seems irrelevant — in the midst of the second world war, academics still found time to write philosophy — but it’s a case that has to be made. If not, universities will either be defunded (what is happening) or reduced to job-training and developing lucratic doo-hickeys (a worse fate, arguably).

Could you please provide footnotes to where you’re obtaining your financial data? You make the point that Ontario is last in terms of funding post-secondary education, but the Fraser Institute indicates otherwise.