This blog post is adapted from a presentation I gave last week at the European Universities’ Association’s Funding Forum in Helsinki. My colleague on the panel, Enora Pruvot, was tasked with summarizing funding trends from the perspective of European institutions; mine was to zero in on the world’s 11 biggest spenders on tertiary education outside Europe, which is why you won’t see data in here on places like France, Germany, the UK, or Spain. (Why eleven? It was supposed to be ten but I went down a rabbit hole and lost track.) Anyways, I hope you enjoy it. As usual, all figures are adjusted for inflation.

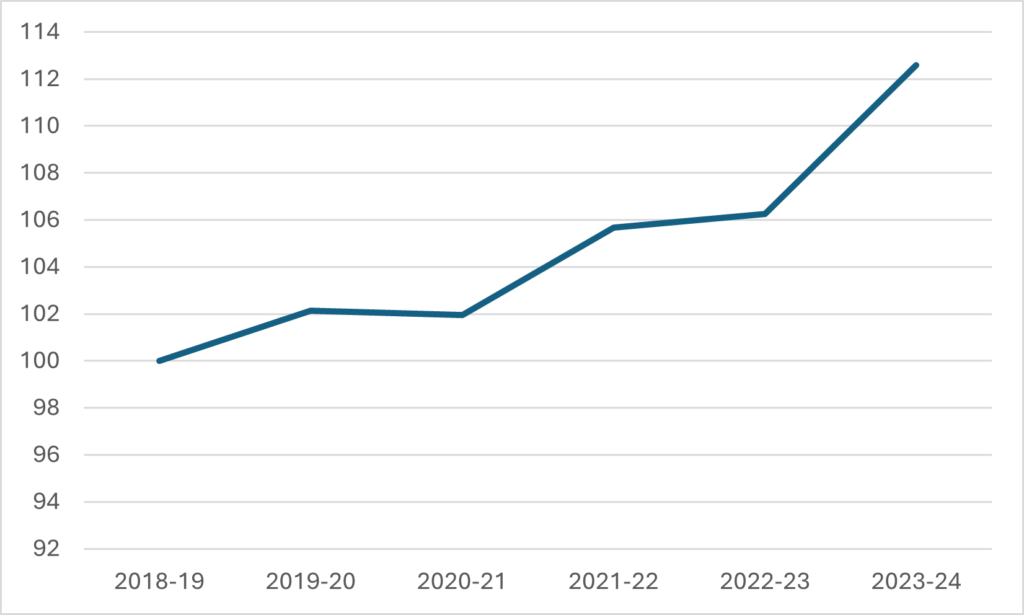

When looking at funding trends around the world, you have to start with the United States. Even leaving the super-rich sector of private non-profit institutions like Harvard, Stanford, etc., its public sector remains the biggest in the world. Tracking funding in the US is difficult because of the way the US government chooses to label both its student aid funding and its R&D funding. But as near as I can piece together from the data, over the five years 2018 to 2023, both state funding and federal R&D funding grew by a little over 12%, excluding any COVID emergency funding (much of which in any event ended up in the hands of students rather than institutions).

Figure 1: US Public Spending on Tertiary Institutions, 2018-2023 (2018= 100)

This is not the story you often hear about the US, with so many institutions claiming hardship and instituting cuts. The reason for the dissonance is two-fold: first, an awful lot of this new money has not in fact benefitted institutions because it has been delivered with strings attached, the main one being frozen or reduced tuition fees. Second—hey, it’s a big country and its higher education sector contains multitudes. Some institutions are well-managed and others (hellooooo U Arizona!) are not. But in any event, these are some significant increases.

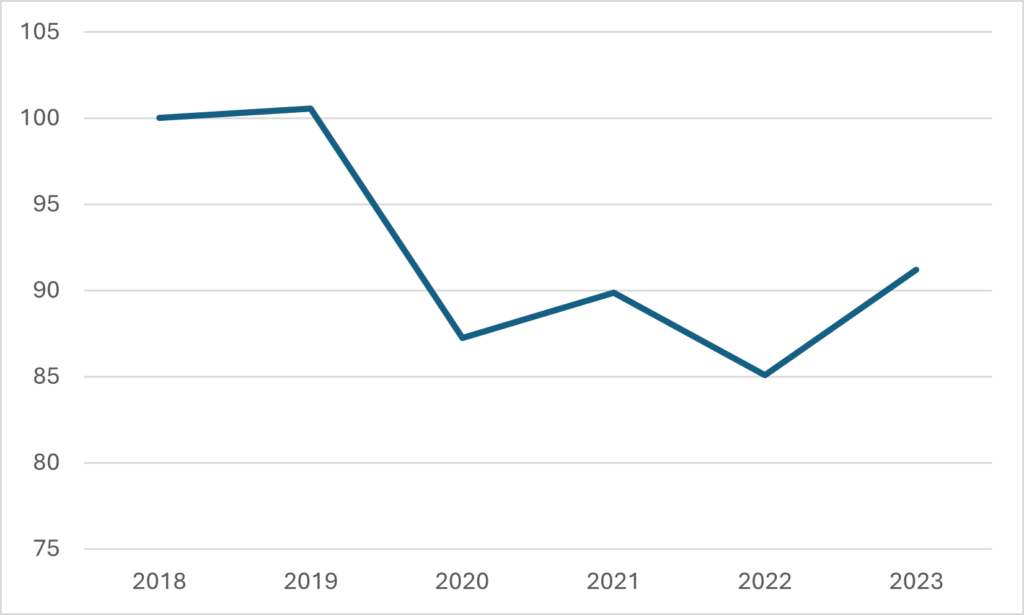

Remarkably, we cannot say the same thing for China. I know lots of people have this image of Chinese higher education as being this unstoppable train going from strength to strength on the basis of huge government investments, but that picture hasn’t been true for over a decade. Yes, prior to 2013, public investments in higher education were rising at 10% or in real terms more annually, but once Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, that figure dropped to about 2% until 2018. Since then, though, growth has been negative. COVID hit hard, and the system has yet to recover. In 2023, total real spending is down about 8% from its levels in 2018. That’s not a huge brake on the very top institutions which—as I showed in a blog a few months ago—get most of their funding through corporate sources rather than governments. But outside those to institutions, this decline is a big deal.

Figure 2: China Public Spending on Tertiary Institutions, 2018-2023 (2018= 100)

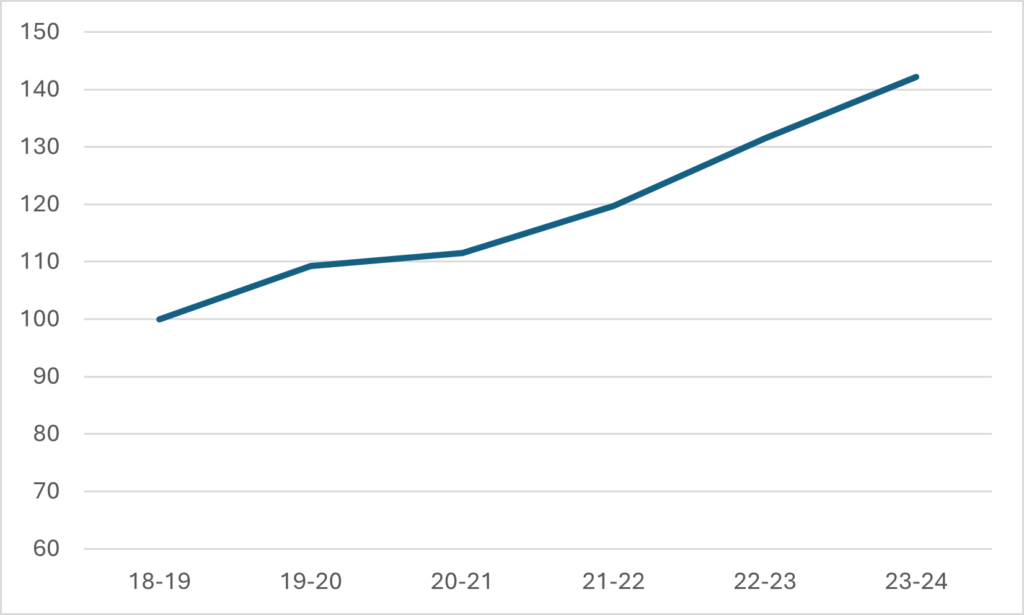

Crossing the Himalayas to India, data here relate only to central government expenditures on central institutions and the IIT system, which is probably only about half of the total. But wow, this is some increase. Even after some pretty significant inflation, government expenditures are up 42% since 2018 (though, that said, government expenditure declined significantly the year prior to 2018 so this is partly just a phenomenon of measuring from a low baseline). Expenditure increases were actually much larger in the Central universities sector than in the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs).

Figure 3: India Central Government Pubic Spending on Tertiary Institutions, 2018-19 to 2023-24 (2018-19= 100)

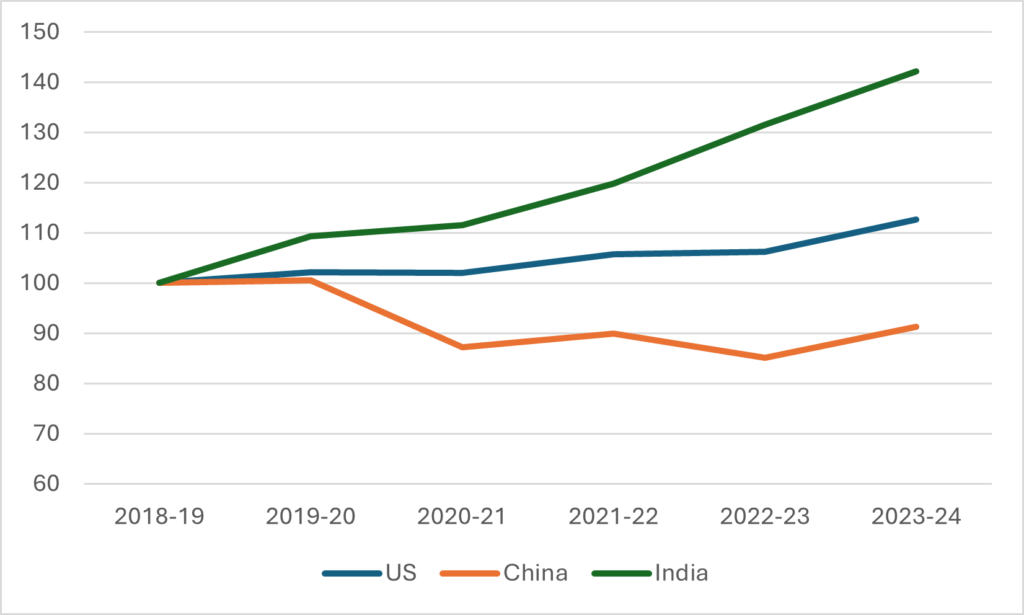

Got that? So across the world’s three largest post-secondary sectors, which collectively make up well over 40% of total enrolments, you have three totally different experiences over the past five years: strong growth in the US, moderate but healthy growth in India, and outright decline in China. Not much of a global pattern.

Figure 4: Comparison of the “Big Three” Pubic Spending on Tertiary Institutions, 2018-19 to 2023-24 (2018-19= 100)

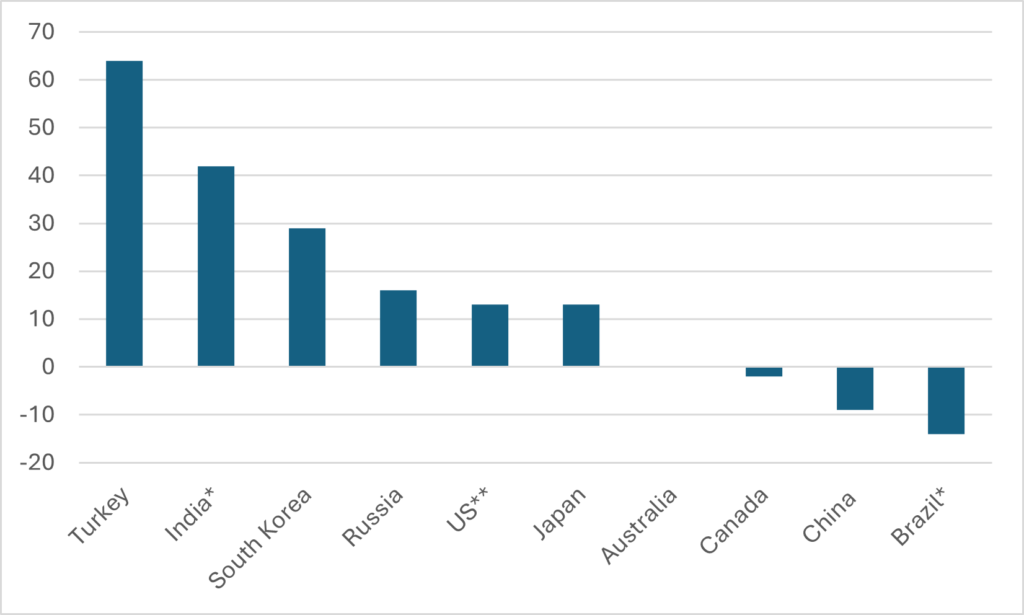

I’ll spare you the blow-by-blow across the rest of the countries and just present a single graph (figure 5) to present the five-year totals across the rest of the non-European world’s “Big Eleven.” Turkish institutions are the biggest winners in this category: real growth has been choppy due to massive inflation, but overall real expenditures on public universities grew 64% between 2018 and 2023. The figures for South Korea are for operating grants only, but they have shown some big growth particularly in the last two years. Russia, somewhat surprisingly saw growth in its public spending on universities even into 2023: it will be interesting to see if this continues on a sustainable path or not. Japan has seen its first big rise in public spending in a couple of decades; intriguingly, nearly all of the growth has been in competitive funds rather than operating grants. Saudi data on university has becoming increasingly opaque over the past few years, but as best I can tell, it continues to increase.

Figure 5: Five-Year Change in Real Public Spending on Tertiary Education, Most Recent Five Years Available, Top Eleven Systems Outside Europe

Australia has been a little bit up and down (there was a surge of funding in 2021 as a result of COVID), but in real terms its 2022 spending was exactly the same as its 2017 spending. Canada, y’all know about. Brazil is the big loser here, with 2023 spending at a mere 88% of 2018 levels (like India, Brazil’s spending is only recorded at the federal level—consolidate state level data is unavailable). However, all of that decline happened on Jair Bolsonaro’s watch: spending began to recover in 2023 after Lula da Silva was brought back to power.

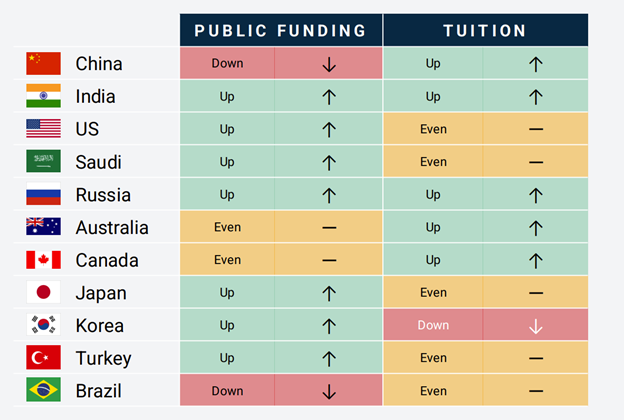

An interesting question is the extent to which tuition fees are amplifying these trends or not. In Figure 6 I have simply compared national trends in tuition fees with national trends in public funding. And like Figure 5, it’s all a bit of a mishmash. India and Russia are the only places where both public and private funding are increasing, and in Russia’s case it is from very low levels (most but not all students at public universities have free tuition). In some cases, increases in public funding are largely going to subsidize tuition fees rather than improving institutions’ financial position. Canada’s strategy—charging the living daylights out of international students in order to make up for governments’ refusal to invest public money—is shared only by Australia.

Figure 6: Public Spending and Tuition Income Trends, Top Eleven Systems Outside Europe

Anyways, that’s my data dump for today. I’m not sure there is much to glean from all this in terms of global trends. There’s a lot of stuff going on out there, but it’s highly state-specific and there’s not much in terms of broader trends. Maybe the only thing to underline here is that China—which spent much of the first two decades of this century as the undisputed champion of increased investment in higher education—has now definitely lost that position.

It’s a different, more multi-polar world. Strap in.